Return to Rancho La Ceja

Journalist Macarena Hernández on the wings of one family, two homelands

AUTHOR’S NOTE

I was lucky enough to get to write the story of my grandparents’ rancho, my mother’s birthplace in Mexico. Titled “One Family, Two Homelands,” this five-chapter series ran in the Lifestyle section of the San Antonio Express-News in December of 2004 and is presented in full here on HTI Open Plaza, along with exclusive photographs and study guides. .

The story recalls a different northern Nuevo León, one where these Mexican ranch lands were epicenters for families on both sides of the Rio Grande. Growing up, I’d always heard the narrative of the “dangerous border,” one of only violence and crime, a narrative that has been in circulation since the beginning of that border. Yet, what I saw was so different from the Mexico portrayed in Hollywood and news cycles. Even as a very young writer, I was determined to write about the ranchos that so many Mexicans had left behind for the United States. El rancho La Ceja was my refuge as a child, the magically zen place where I could escape my crowded home in La Joya, Texas. Rereading this series, I feel immense gratitude for the opportunity to have been able to capture this moment. It is true what they say: If you don’t write it down, it is like it never happened. It is impossible to remember such specific details otherwise.

Our rancho, which has been mostly abandoned since my grandfather died in 2006, was what actually inspired me to become a journalist. I wanted to tell my family story – through the rancho La Ceja, Dr. Coss, Nuevo León, México – back then and nearly twenty years later.

Because places, like people, die, too.

-

We knew death roamed near. We expected it to take my grandfather first. He's the one with cancer. But then my grandmother began to murmur the names of her dead.

Months later, my ‘uelito José María, wearing his tanned felt cowboy hat and his khaki pants, sits in an empty chapel a few pews from my grandmother's casket, waiting for the permit to take my ‘uelita Cecilia's body back to Mexico.

Outside, the U.S. flag flutters in the almost-vacant parking lot, where a gleaming white SUV hearse waits to transport our dead and dying back home. In our rancho in La Ceja, more than 200 friends and relatives wait for Uelita Cecilia's arrival.

Nostalgic Mexicans are like monarch butterflies, always remembering home.

-

They used to call my grandfather el rey sin corona—the king without a crown.

At 89, José María Reyna still walks with his shoulders erect, his chest open with pride, his head cocked back and cowboy hat tilted to the right. He wears his felt Stetson to the cancer clinic in the United States and his worn-out straw sombrero when he's on his rancho in Mexico.

Until recently, there was always a .22 or .38-caliber handgun strapped to his waist. Pistolas lindas, he calls them. Pretty pistols.

"I never liked carrying it on the outside, and I always had a license to carry it," my grandfather says. "But I carried it tucked in my belt, sticking out just enough so it could show its cachas," its face.

My grandfather talks lovingly of his pistolas, as if they were women: For most of his life, he has had at least two of each.

At one point, my grandfather was also the school's treasurer, provided security at weddings, and counseled couples in troubled marriages.

-

My mother has her mother's small and delicate nose. And she has her father's sagging eyelids and his strong and stubborn ways.

She is the one who tells Uelito José María sus verdades, the truths our family has always preferred to ignore. Still, after my grandmother dies, he comes to live with her.

"If you don't want me here, I can go back to the rancho," Uelito José María says, usually after my mother has reminded him that she is no longer a little girl, he can't tell her what to do.

My grandfather says my mother's carácter fuerte, strong character, comes from his mother, Uelita Lola. One look at a pregnant woman's belly, and Uelita Lola, a midwife since she was 13, could tell whether the mother was carrying a boy or a girl. Uelita Lola was hardly ever wrong.

-

My mother often threatened to disappear—either back to the rancho or on the day of the Rapture.

She reminded us of her plans, especially on those long, tired days when nobody seemed to appreciate that she washed and cooked for a family of ten.

"The day will come when I will leave this place. One day you won't find me," she told us in her melodramatic Mexican telenovela tone. "Then you will realize how much you need me."

My parents always spoke of one day going back to Mexico, where they imagined a much simpler life.

Only the dead or deported return.

-

I go to La Ceja to remember what I don't want to forget. My grandfather goes to La Ceja to forget what he doesn't want to remember. In La Ceja, he is still el rey, the king, though almost everyone else has left for the United States.

Alli, sus chicharrones todavía truenan: There, his pork rinds still crackle.

"En el otro lado [in the United States] all you do is watch television," my grandfather says. "Just sitting in front of a television in an air-conditioned room. You go from your bed to the living room to the kitchen to the bathroom. Eso no es vida."

That's not living.

His dreams are stuck—atascados—in time. His children are always young when he sleeps.

-

Study guide created at Centro Victoria, University of Houston-Victoria (UHV)

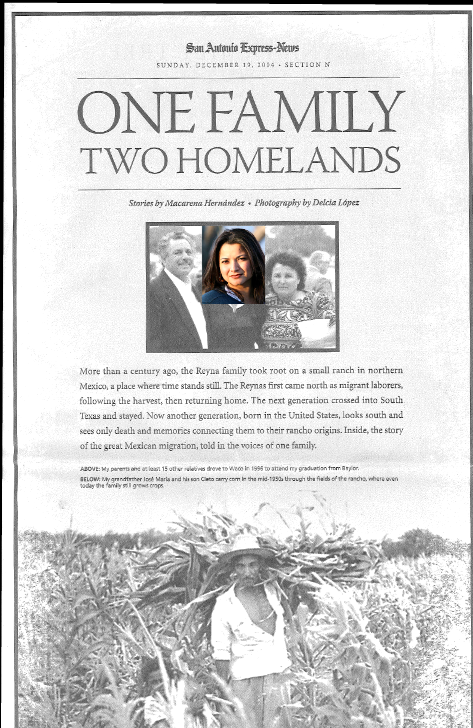

Left: Author photo superimposed over cover page for Macarena Hernández’s five-chapter series “One Family, Two Homelands,” San Antonio Express-News, 19 December 2004.

Chapter 1

Last Ride Home

We knew death roamed near. We expected it to take my grandfather first. He's the one with cancer. But then my grandmother began to murmur the names of her dead.

Months later, my ‘uelito José María, wearing his tanned felt cowboy hat and his khaki pants, sits in an empty chapel a few pews from my grandmother's casket, waiting for the permit to take my ‘uelita Cecilia's body back to Mexico.

Outside, the U.S. flag flutters in the almost-vacant parking lot, where a gleaming white SUV hearse waits to transport our dead and dying back home. In our rancho in La Ceja, more than 200 friends and relatives wait for Uelita Cecilia's arrival.

Only the driver and my grandfather ride with my grandmother on her final journey home. The hearse slows down in La Joya, my childhood home, before driving past the old Banworth packing plant on the hilltop in La Havana, where many of my relatives once chopped and packed onions, cauliflower, and broccoli.

The six cars trailing behind finally catch up as the hearse slowly drives past Sullivan, then miles and miles of green and brown hills with thick patches of brushland, where Starr County begins and Hidalgo ends.

It rolls past the tiny old town of La Grulla and then 10 miles to Rio Grande City, where, at the second light across from the H-E-B, it turns south to cross the Rio Grande—the river that divides this world from the other.

Nostalgic Mexicans are like monarch butterflies, always remembering home.

Las familias Reyna y Hernández are from the desolate dirt roads just south of the Tamaulipas state line– two and a half hours north of Monterrey, Mexico's third largest city, an hour south from the Texas-Mexico border. Still, a world away. Photo: Macarena Hernández

The Journey Home

No one remembers exactly when Uelita Cecilia left La Ceja for the United States. It happened gradually, as her visits to South Texas grew from days to weeks to months, until the last six years of her life, when she completely abandoned her house. The pothole-battered dirt roads on the way to La Ceja made the ride unbearable to her brittle bones, her body so fragile that any sudden movements pushed her ribs up against her insides, causing her physical pain.

"Pray for a peaceful death," I tell her one day, when she's feeling too weak to open her eyes.

"You can let go of this world now. I know you're tired. I'll just ask Diosito to answer your prayers and give you whatever you ask for. But you have to promise me when you reach heaven, you will be my angelito. Will you be my guardian angel?" "Your angelito," she says, barely pronouncing the words as she smiles and touches my cheek. Now I want to make her laugh.

"Well, since you are going to see God," I tell her, "tell him to send me a good man who's not jealous, who will wash his own underwear, and who will let me be me."

"Un milagro," she says, laughing. I'm asking for a miracle.

My grandmother spent the last few months of her life in the back corner room of my mother's house, asleep. At night, she was awake, fearing death would snatch her while everyone else slept. She longed for her house and for her camita de palo, the twin-sized wooden bed where she had spent most of her nights, where she had given birth to nine of her 10 children, and where her firstborn, Abel, was laid the night he was murdered.

Too weak to use her walker, she spent her evenings sitting in the living room, watching telenovelas and asking her great-grandchildren for kisses on the cheek.

Two months before she died, my grandmother met her first great-great-grandchild, Michelle, born in Starr County. My grandmother had 45 grandchildren and 66 great-grandchildren, some of whom called her Uelita Chiquita, because osteoporosis had shrunk her 5-foot-5 frame to about 4 feet.

Only a few of them came to visit during those last months.

Near the end, after her stroke, my grandmother hardly spoke. She mumbled most of the time, and if the listener wasn't patient, she'd give up trying to communicate altogether. Her eyes looked distant, like she was already gone. By then, her children had forgotten the sound of her voice.

The day before my grandmother died, the day before she ended up in the hospital, my mother and my tío Cleto purchased a $3,500 funeral package to be used by whoever died first—my grandfather or my grandmother. The funeral package included the cost of the casket, the rental fee for the funeral home chapel, and $350 to transport the body back to Mexico.

Her body would remain in Penitas, Texas for one night of viewing by relatives who couldn't make it across the border, and then it would be taken by hearse on the 72-mile journey to La Ceja.

Uelita Cecilia spent the last hours of her life in the intensive-care unit of a McAllen hospital.

She died in April on a late Saturday afternoon, with only a daughter-in-law by her bedside as she called out my mother's name, Elva.

My grandmother was only four months from her 90th birthday when she died, during a spring that already promised more rain than usual. One that reminded my mother of beautiful childhood days, when there was plenty to harvest—calabazitas, beans, and corn—and when the presas were always full of water. A spring that resurrected memories of generous skies, healthy, fat cattle, and chewing on sugarcane.

No one plants sugarcane anymore.

The night before we took her back to Mexico, my mother's pastor, el hermano Lupito González, a handsome chaparrito who fixes cars on weekdays and delivers Sunday sermons with a passion twice his size, told the mourners at the funeral home about the times my grandmother visited his church. She found comfort in the word of God, he said, smiling. She had already given her heart to Jesus.

"Gloria a Dios, hermanos," he said. "La hermana Cecilia is in heaven right now, está en el cielo."

Many on the rancho claimed to be Catholics, although the priests only showed up to ask for ofrendas and to baptize the huercos. But when I was a kid, there was a vocal minority of Baptists and Pentecostals, most of them having come across their new religion on migrant farmworking routes north. These were the most forceful believers. Their millennials will prefer nondenominational mega churches. Photo: Macarena Hernández

My grandmother loved God, but she did not like going to church. Unlike my mother, she preferred to pray in her room, alone. She loved to sing, mostly Mexican lullabies and songs to the Virgen de Guadalupe, even though she had reluctantly become a Protestant after some of her born-again Christian children insisted. Praying to saints is idolatría, they told her, a violation of one of the Ten Commandments. Before long, all her santos—including la Virgen de Guadalupe in the tired wood frame—were gone from her house.

At the service, Armando Flores and his wife Criselda, La Chacha, sing about crossing rugged valleys on your way to heaven, about mansions of light and streets made of gold, about finding peace. Chacha has known my family most of her life. Chacha's father and my grandfather were the poker kings of the rancho, both cheaters who never cheated each other.

The next day, the freshly washed hearse with clear, spotless windows crosses the Rio Grande, driving away from a lost and unimaginable future and into the fading but alluring past. The caravan drives farther south along the San Juan River and into the noisy, hot streets of Camargo, where it passes my mother's favorite tortilla shop, Tortilleria Cuauhtémoc, named for the last emperor of the Aztecs.

The hearse speeds through the small fishing town of Comales, where my father's parents died—first his mother, then his father, seven years later. The speed bumps at the entrance to the pueblito of Ochoa slow the hearse down as it drives past my father's first cousin Lupita's house, where I ate homemade dulce de leche, the milk candy she sold from her kitchen. They drive past the taco stand in Santa Rosalia, where, at night, locals gather to eat and watch telenovelas, and past the last store before the rancho, one of the few tienditas that still sells the fresh cheese made nearby.

They stop at the checkpoint a few miles down the road, just before the Tamaulipas and Nuevo León border. There, my grandfather points to the caravan and tells the customs officer of his dead wife. The Mexican bureaucrat waves half the cars through and sends the others back to the border, where they could either get a temporary vehicle-importation permit or go home.

At one time, most of the customs officers at the checkpoint were conocidos, family friends. They rarely inspected cars, and there were no red lights prompting random searches. My father's uncle, Tío Julio, used to work as a customs officer, and on our drives back from the rancho, we would stop and drop off fresh eggs, tortillas, and homemade cheese.

One day, the government fired all the locals and replaced them with men who came from other Mexican states. They looked more like soldiers than customs officers.

Petróleos Mexicanos (Pemex) workers drilling for black gold brought some paved roads and business to Serafín, Mexico. Not enough for most to live on. But not everyone can get a Pemex job. Those men come from elsewhere. El Cartel pays the locals to be watchmen. $300 per month. $200 more than ISIS. Best job in town. Photo: Macarena Hernández

The caravan crossing the Tamaulipas state line into Nuevo León continues south on the paved road, turning right at el rancho La Bandera, which is a straight shot to La Ceja. The cars drive until the paved road ends and the dirt one begins as they speed past Serafín, where Pemex workers drilling for natural gas live at the Elizondos' old house, abandoned 15 years ago when Lolo, the patriarch, died. The caravan takes a left just before the school, the only building for miles on that stretch of dirt road. Classes for the six students have been canceled because of my grandmother's funeral.

The cars that the customs officer turned back arrive after my grandmother's coffin is placed in the corner room of her house, which had been cleared of two full-size beds, one ropero, dresser, and the sewing machine that sat unused for decades. The latecomers had decided to test their luck and drive through back roads and across private ranchos at the risk of getting caught by customs officials.

Most of the mourners are outside, scattered throughout the Reyna family rancho, 70 acres of rural Mexico, home to my grandfather's parents, Uelita Lola and Uelito Cleto, and his great-grandparents, Tatito Pancho and Nanita Manuela, among the first settlers at La Ceja, the eyebrow.

Some relatives had arrived the night before. My tío Cleto slaughtered a cow, and my mother's sisters helped chop it up for beef stew. They set up picnic tables in the carport, where my grandfather parks his hand-painted, cobalt-blue Ford truck and where my grandmother's hens nested their young in empty Gamesa cardboard boxes.

The men drink Budweiser and Carta Blanca around their pickups and next to the chicken coops by the goat pen. The boys drink their beers and smoke their cigarettes away from the house.

It is the middle of a Monday afternoon, the hottest part of the day and around the time my grandparents José María and Cecilia used to take their afternoon naps. My grandfather still doesn't want to think about burying my grandmother. My relatives worry that he will want to wait until Tuesday to bury his viejita, his wife of nearly 70 years. People have already missed a day of work, they say.

Life doesn't stop when someone dies.

My grandfather tells me to tell my tías, who are asking that we will bury Uelita Cecilia al ratito, in a little while. He wants to keep her body in La Ceja longer.

There haven't been this many visitors to our rancho in nearly 20 years, since Uelita Lola, the matriarch of the Reyna clan, was buried. For eight days, the rancho did not sleep. Relatives and friends watched and waited for death, staying by Uelita Lola's bedside until her last breath.

Death always brings us together.

We feast at funerals. Get reacquainted. Those who left with those who wouldn't or couldn't. Later, as we drive away, we'll lament their lack of options. Wonder what will become of them. Photo: Macarena Hernández

Today, women sit on chairs and rock on sillones lining the cold, sand-colored concrete walls of the house. The mourners crowd into every room, including the three bedrooms, where they sit on beds or steady themselves up against walls. Some, including my mother's youngest sister Lola, stay by the coffin most of the day. Lola, the youngest child, la coyotita, was born when my grandmother was 46. She was so tiny, my tía, that she fit in the palm of my grandfather's hand.

"I think it's dumb that the only time we get together is when we are going to enterrar a alguien [bury someone]," my tía Lola's oldest son, Abram, 22, says as he sits by Tío Abel's house, where he and my younger cousins are drinking their beers. "I have a friend, and they have family reunions, and they even make shirts that say ‘ésta es la familia So and So.’"

My tío Nicho Salinas and his wife Dolores drove down from Dallas, where his mother, my grandfather's sister Rosario, has lived for more than 30 years. Her family used to visit the rancho more often, but that was before 1968, when Rosario's son Carlos died a month after a cousin, my mother's younger brother, accidentally shot him one alcohol-fueled night. Nicho, the oldest of her 10 living children, is the only one who still comes back, mostly for funerals and the occasional wedding. Carlos was buried back in the rancho, a few feet away from my mother's brother Abel.

The women, mostly the older ones, sit around the kitchen table, reminiscing, crying, and, at times, laughing.

My mother's sisters and distant tías talk about their growing waistlines, about death and its inability to discriminate, about my grandmother, who looks peaceful, like she's sleeping. Soon, the conversation shifts to marriage and my approaching 30th birthday—and still no husband, they lament.

"You don't want to grow old alone," one of them says. "You need to find a good man, un hombre bueno, to take care of you."

"Don't even get married," another one says. "Ni pa'que te cases."

My grandfather never asks me why I am not married, and he is the only one who doesn't seem to care. My mother has been praying for a good son-in-law for most of my life, and my tía Nelly even took me to a curandera to make sure my love life wasn't cursed.

A few of my cousins, a nephew, and I (center left) ride in the back of the pickup carrying my grandmother’s body to the rancho’s cemetery. Sobbing by the foot of the coffin is my cousin Miriam (third from right). My cousins and I haven't been in the back of a pickup, driving through the ranchos, since we were kids, hitchhiking to the Elizondo store in Serafín. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

The Burial/El entierro

My grandmother had asked us to bury her with the blanket her mother gave her and what was left of my tío Abel's belongings, including his wife's wedding dress. Before we take her to the cemetery, we ask the guests, mostly distant relatives, to give us a few minutes. My aunts don't want people gawking at us as we place the wedding dress inside the coffin, which my mother says will ignite rumors, gossip, chisme.

"Ay no, they might say it's some kind of brujería [witchcraft]," my mother says. In my grandmother's petaca, the old scruffy black trunk, we find more wedding mementos.

My cousin Isabel and I decide not to stuff her coffin with everything: the veil still attached to the peineta, the bouquet, the wedding scrapbook, and the two cojines that were once fluffy and white. My cousin takes the tattered, pointy white leather shoes worn on that Saturday night in 1964, when Abel married his girlfriend Margarita García.

But we can't find the shirt he wore the night he was murdered, the one my grandmother kept in her trunk, still stained with his blood. One of her daughters says one of them washed it and threw it away years later. But no one is really sure what happened to Tío Abel's shirt. Uelita Cecilia had wanted to save everything, including his belt and his comb, but her other boys didn't own much, so she gave them his clothes, cowboy hat and boots. His brothers wore his clothes for years after his death.

Isabel plans to take the two deflated cushions with her back to Pharr. Although she knows some of my aunts may wonder why she, a divorcée—the first granddaughter to earn that distinction—would want to hold on to someone else's wedding memories, but she wants a recuerdo, something, anything that will remind her of my grandmother.

My tía Juana Quintanilla, who couldn't afford to come to the funeral from California, asked that we save her a pair of my grandmother's thick support hose, which were always two shades darker than her caramel-colored legs.

"I want to wear them the day they bury me," my tía Juanita told me over the phone. She also asked her sister Lola to videotape the burial for her, but her grief will be too much, and Lola never takes the camcorder out of her car.

By my grandmother's feet, I place the wedding dress, with its yellowing lace. Next to it, a dusty black plastic comb, a canvas belt attached to a dull and scratched metal buckle, and, folded neatly, a long-sleeved cotton shirt.

My youngest sister, Nancy, helps me place the blanket stitched from faded cotton scraps under my grandmother's head, just as she had asked.

"No se les vaya a olvidar," she had told us. Don't you all forget.

A plastic H-E-B grocery bag at the foot of her coffin holds a few pairs of her cotton underwear.

The rest of her belongings will be given away: her ropita, clothes; the unopened boxes of diapers she refused to wear; and the black-and-white checkered hand purse that, like her, went hardly anywhere. Some of her children and grandchildren each take one of her batitas, housecoats made of cotton and flannel, the only kind of dress my grandmother ever wore.

Her sons and grandsons carry her silver-colored coffin and load it onto the bed of my grandfather's pickup. A few of my cousins, a nephew, and I ride in the back. Sobbing by the foot of the coffin is my cousin Miriam, a 21-year-old college senior in Denton who lived at the rancho until she turned five, and her parents moved to the Rio Grande Valley.

My cousins and I haven't been in the back of a pickup, driving through the ranchos, since we were kids, and we hitchhiked to the Elizondo store in Serafín. At night, after dinner, we would ride in the back, on our way to my tía Lupe's house, where the adults drank coffee as they gathered on the porch, talking for hours with only the light of the moon and the stars. In the distance, you could hear the pack of coyotes wailing from the top of the small rolling hills.

Left to right: My mother María Elva, my grandparents Cecilia and José María, and my aunt Lupe at her kitchen, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2003. Even when everyone else had left Mexico, my tía Lupe and her husband Lico remained. When my mother visited from the United States, we would all drive down the gravel door—a few miles north—to sit in Tía Lupe’s kitchen and tell stories. Photo: Delcia Lopez / San Antonio Express-News

But today, we sit silently by the coffin as my grandfather shifts gears on our two-mile drive to the cemetery, where, 38 years ago, he buried his son and then his own father a year later.

My father buried his mother there in 1985. I buried my father there 13 years later, two weeks short of my 24th birthday.

We drive past acres of scrubland, the cacti crowned with yellow and red flowers.

The rattlesnakes have already woken from their winter sleep.

At the Sara Flores cemetery, Armando, Chacha's husband, offers a short sermon. And he cries like I've never seen a Mexican man cry before, his sermon choked with tears. I wonder if he cries for my grandmother or for his son, who has been missing for more than 10 years. They say he was kidnapped. His body has never been found.

Afterward, my tío Erasmo, Miriam's father and a construction worker who fantasizes about singing rancheras on stage, sings a song he wrote himself on the flight down from Chicago to Texas. My cousin Abram, a self-taught musician with an eye toward producing music, lets his accordion weep as Armando tries to follow along with his guitar.

Standing in front of the coffin, my grandfather cries openly for the first time his grandchildren can remember. He touches my grandmother's face and then pats her head before kissing her forehead. The sun is setting, and what is left of his thin white hair blows in the dry evening air.

From somewhere, I hear someone say my grandfather looks old, like he is withering. Uelita Cecilia had wanted to be buried next to her oldest son, but there is only a small patch of dirt, barely enough space to fit one, and my grandfather has already told us he wants to be buried next to her.

So, instead, her grave was dug by the tombstone of Rubén Treviño, my grandfather's nephew and faithful deer-hunting partner. He died in Rio Grande City in December 1998. His family buried him back here in Mexico, not far from where his father and mother Albina, my grandfather's sister, still live. One of his sons poured beer over his fresh gravesite as Ramón Ayala y Sus Bravos Del Norte blared from the speakers of a pickup, its doors swung open: no tears at the funeral, only guitars, the song says. He wanted to be buried with music.

We sing hymns in Spanish from Catholic, Baptist, and Pentecostal services, just like my grandmother had wanted. I ask my mother's friend, la hermana Herlinda Gallo Lara, to sing until the last flower arrangement is placed on my grandmother's grave. We sing the same cantos two and three times. Streets of gold. A mansion of light. No more pain. Over our song, we hear the loud thuds of dirt hit the coffin, and I hear my mother's youngest sister, Tía Lola, sobbing. She can't understand how this is the last time she'll see my grandmother, her madrecita. She had been the keeper of my grandmother's secrets. When she got married and moved away to Houston in 1981, I became my grandmother's reservoir.

My brothers, male cousins, and uncles take turns shoveling dirt, until there is no more tierra left to shovel. Even after everyone has left, my grandfather wants to stay.

He stands by her fresh grave. For the first time in his life, Uelito José María looks like a broken man.

Standing in front of my grandmother Cecilia’s coffin, my grandfather José María cries openly for the first time his grandchildren can remember. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

Chapter 2

Pretty Pistols

They used to call my grandfather el rey sin corona—the king without a crown.

At 89, José María Reyna still walks with his shoulders erect, his chest open with pride, his head cocked back and cowboy hat tilted to the right. He wears his felt Stetson to the cancer clinic in the United States and his worn-out straw sombrero when he's on his rancho in Mexico.

Until recently, there was always a .22 or .38-caliber handgun strapped to his waist. Pistolas lindas, he calls them. Pretty pistols.

"I never liked carrying it on the outside, and I always had a license to carry it," my grandfather says. "But I carried it tucked in my belt, sticking out just enough so it could show its cachas," its face.

My grandfather talks lovingly of his pistolas, as if they were women: For most of his life, he has had at least two of each.

Around the humble, but sprawling ranchos of the municipality of Doctor Coss, in the Mexican state of Nuevo León—La Ceja, Serafín, Altamira, and La Reforma—everyone called my grandfather by his nickname, Chema. Until two years ago, he was a volunteer police officer, patrolling these four ranching communities—a job he held for more than 40 years.

At one point, my grandfather was also the school's treasurer, provided security at weddings, and counseled couples in troubled marriages.

My mother says my grandmother's comadre first suggested the king-without-a-crown title. But my grandfather tells me it was his friend Raúl Moreno, whom he calls Raúl Pelón, Baldy Raúl, who first crowned him el rey sin corona.

My grandfather, his friend observed, traveled with an entourage, usually local políticos from the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI), who were on the campaign trail. My mother has always told my grandfather he sold his loyalty to the PRI for cheap: empty promises, cheap quilts, and pantry food.

Much has changed since. After 70 years, the PRI no longer rules Mexico. And now, the king, my grandfather, is dying.

"I dream of my viejita almost every night. She wants to take me," my grandfather says. "I'm already looking at my grave, waiting to be buried. I wish I could be born again so that I can see more, but that's impossible. I don't have much time left."

My grandfather's world is nearly gone, pushed out by the faster-paced one just across the Rio Grande. Gone are the nights when he roamed the ranchos, first on foot and later in his Ford pickup, with his right hand firm on the stick shift.

Still visible on my grandfather's face, his sun-weathered skin the color of dried mud, is a bullet nick above his high left cheekbone from a Saturday-night shootout in 1948, when he was 33.

The argument started during a dance in the school's courtyard, where every 10th of May children used to pledge their devotion to their madrecitas, reciting tributes that left their mothers openly crying and sobbing, lagrimeando y llorando a grito abierto.

Most of the people who had been dancing that night had already gone home when Rosalío Salinas fired the first shot, my grandfather begins to tell me one afternoon as we head over to a nearby Red Lobster after his weekly chemotherapy session in McAllen. "How much does a fish plate cost here?" my grandfather asks just before walking in. I wave off his worry and tell him to come right in.

Settled at a dimly lit table, my grandfather continues his story of that night, a night that inspired the blind musician David Leal, from nearby Santa Rosalia, Tamaulipas, to write a corrido, a ballad called "José María y Rosalío."

My grandfather calls Rosalío by his nickname Chalío.

"Apasíguate, Chalío, ya te dije," he recalls telling him several times, after Chalío broke two beer bottles he had refused to pay for. "Settle down, Chalío. I've warned you."

Chalío fired a shot.

The lamps around the dance floor had already been turned off when my grandfather ran for cover behind the nearest mesquite tree. Uelito José María loaded his beat-up and unreliable .765-caliber pistol and fired back eight bullets. Three hit Chalío, one piercing the brim of his tan cowboy hat, another grazing his rib cage, and the other striking near his crotch, my grandfather notes with a grin.

He spent the next 15 days in a jail cell while Chalío recuperated at a nearby clinic. "We fixed things and stayed friends," my grandfather says. "But I never really trusted him after that. If he could have, he would have shot me in the back, a traición."

He pushes away his salad and chugs the ranch dressing right from its little paper cup.

“Señor, bendice nuestro hogar [Lord, bless our home]”: The Reyna Salinas family crest at Rancho La Ceja, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2004. Photo: Macarena Hernández

The First, The Favorite

My grandfather brought his 20-year-old bride Cecilia Salinas to the family rancho in La Ceja, in 1935. The ranching community was then home to a handful of other families, all relatives, mostly Reynas and a few Gonzálezes.

There was only one little hut, nesting in the middle of the monte, surrounded by mesquite trees, chile piquín, cacti, and medicinal plants that could cure colic, colds—and even, some claimed, broken hearts. By the time I was born, there were three cinder-block houses on the property.

My great-grandmother Lola's house, the tiniest of the three, sat next to the corrals her grandson Abel had helped build when he was a young boy. My grandfather's hired help—poor, young families from other Mexican states—have occupied Uelita Lola's house since her death in 1987.

My grandmother Cecilia gave birth to Abel in 1936, the year that marked the beginning of the most elegiacally romantic period in Mexican cinema, la época de oro, the Golden Era.

Spanning two decades, it launched the careers of some of Mexico's biggest movie stars. There was Pedro Infante and Jorge Negrete, Tin Tan and Resortes, Dolores del Río, and you can't forget La Doña—María Félix—who died two years ago on her 88th birthday, although she claimed she was much younger. She had many lovers and her share of husbands.

"I cannot complain about men," the actress once told a reporter. "I have had tons of them, and they have treated me fabulously well. But sometimes, I had to hurt them to keep them from subjugating me."

My grandmother was no María Félix. Uelita Cecilia was the devoted wife of a man not so devoted.

"'You're better off crying as a poor woman than a lonely one,'" my grandmother said her mother told her. "My mother never advised me to leave my husband because only she knew how much she had suffered when my father died. She would ask me, 'Well, has he ever failed to provide food on the table?' Pues, que no. 'Then you have no right to leave him.'"

Despite the rumors that got back to her, my grandmother never considered leaving my grandfather. She loved him. She would never leave him. Nunca.

"He says he can have 40 or 50 [women], but I am his preferida," his favorite, my grandmother said. "I'm content with that, because he has never left me. Con eso me conformo. They tell me that it's really my fault, because I never left him. But I want to see my children together, united, until the day God decides to take me. Even though I suffered and continue to suffer, I have managed to keep my children together."

That same year, Abel was born; the nearby town of Comales sprang to life when construction began for the largest reservoir in the state of Tamaulipas, the Presa Marte R. Gómez.

Thousands of men from all over the country, including my father's father and others from the ranchos, dug out the dam.

Presa Marte R. Gómez, Tamaulipas, Mexico, ca. 1950. Source: Mediateca Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH), México

Comales soon became a thriving town, with 24-hour pool halls where men drank Carta Blancas after work and where the rich enjoyed the luxuries of a theater and a hospital. Carloads of construction material arrived daily at the railroad station, and before long, the northern part of town was dotted with tipo americano homes, expensive American-style homes where my father's mother, Uelita Ricarda, washed and ironed other people's clothes.

By the time the reservoir was completed nearly 10 years later, my grandmother Cecilia had given birth to five more children: two more boys and three girls, including my mother. She had also buried her first, Juanita, who was only a month away from her first birthday when she came down with an uncontrollable fever.

With a growing family, my grandfather came to Texas to pick cotton for $3 a day, six days a week. He hated stuffing sacks of cotton and quickly learned that hiding a few heavy mesquite trunks in the bottom of each costal could cut his workload in half.

What my grandfather loved of the early 1950s was the nightlife, the tiny rooms, swirling cigarette smoke, and Mexican men— braceros—who came to work because the United States had asked them to–begged them, really. My grandfather learned that lucky poker streaks had nothing to do with suerte and everything to do with skillful manipulation—sanded-down edges and needle-size punctures located on different corners of his cards, easily identifiable through the back.

With minor alterations to his deck—and a sidekick pretending to be a cautious relative with no desire to gamble—my grandfather found an easier way to make money to send home. Uelito José María brought back to the Nuevo León ranchos the skills he learned from a first-class cheater from Monterrey, also a bracero working in the Texas towns of Pecos and Edinburg.

Like so many teenage boys, my tío Abel first left the ranchos with his father to work as a bracero, and later in construction in Dallas and Chicago. It was during one of his trips to the States that he brought my grandmother a black Singer sewing machine. During many of my childhood visits to Mexico, I watched my grandmother happily using it in the spare bedroom, where we grandchildren slept. The sewing machine faced a window overlooking the orange groves Abel planted the day he would be murdered.

My tío Abel, whom I love through borrowed memories, reminds me of Pedro Infante, the incomparable leading man of the Mexican silver screen's Golden Era, whose characters were always the underdog and whom everyone fell in love with, including my mother and me. The actor died in a plane crash in 1957, although, like Elvis, there are sightings of him to this day. He was beautiful and so was my uncle, a sharp dresser and one of the first men from that corner of Nuevo León to drive a car through the ranchos.

Mexican silver screen's Golden Era actors María Félix (“La Doña”) and Pedro Infante, shown in a still from the 1957 award-winning film Tizoc: Amor indio, Infante's last film before his death in a plane crash that year.

Abel was elegant, not like the other men from the ranchos. He had a penchant for crisp, white guayaberas that he wore with khaki pants. His shoes were always polished and scuff-free.

My grandmother had nine other children, but Abel would always be her consentido—her favorite, her protector. As a young boy, he promised her that someday he would build a house next to hers so he could always look after her.

On the last Saturday night of 1963, my uncle met his media naranja, his perfect match, Margarita García, a city girl whose fair skin and soft hair made even his younger sisters envious, celosas.

Shortly after they fell in love, Margarita, an orphan, came to live with a relative in nearby Altamira, where she waited for her wedding day. Their favorite song was Los Alegres de Terán’s "Mis brazos te esperan" (1963), my arms wait for you.

Married within a year, my tío Abel built Margarita a cinder-block house next to his mother's, the third and last house built on our family land.

"Back then it was beautiful, but there was also a lot of shootings at dances. It was very common," my tía María Elizondo, my mother's first cousin, tells me. "Men used pistolas often. You couldn't go to a dance without hearing that fulano o mangano [so-and-so] had been shot at."

By then, the ranchos were overcrowded with teenage girls and young married couples. Every year, along the road that led to the school, families gathered to watch men race horses and fight roosters. The men competed in el palo encebado, struggling to climb the highest on poles slathered with lard.

There were ranchos of all sizes—10 acres to 2,000—most producing just enough food to feed their families.

Hundreds of people gathered at the only school in the vicinity, Escuela Anacleto Reyna, named after my great-grandfather Cleto, who donated the land. My grandparents also named one of their children Anacleto, "Cleto," after him.

"If there was a dance in one of the ranchos, you usually heard guys saying, 'We're waiting for the girls from La Ceja,'" my mother's younger brother Cleto recalls. "'If las huercas from La Ceja don't come, we already know this dance ain't going to be good.' There were just so many girls in the rancho."

A Misunderstanding

Word of the dance in nearby Monte Cristo spread quickly through the ranchos one Saturday in November 1966, and by the afternoon, my grandfather had decided he would go. He'd already invited Abel, who had spent that day planting orange trees by the side of his house. His pregnant wife asked him to stay home.

My grandmother recalled, "He came over and gave me a hug, and I told him, 'Aren't you going to have dinner, hijito?' He said, 'No, Mamá, I'll eat when I come back.'"

Tío Abel drove my grandfather to the Cantus' family rancho in his maroon 1957 Chevrolet, the one he bought in the States with his construction paychecks. They hadn't been there long when an argument broke out, and my grandfather turned his flashlight on the crowd swarming around a compadre and two drunks who refused to pay for their beers. Tío Abel paid for their Carta Blancas.

It was all a misunderstanding, my tío Cleto, the family historian, now says. They thought my grandfather had pulled out his gun. Not long after the argument, Delfino "El Nene" Cantú and his brother Plácido, from nearby Santa Fe, confronted my grandfather. "Come on, you pulled out the gun on my brother," El Nene Cantú told my grandfather, gun pointed at him. "Come on, pull yours out."

"I didn't pull out my gun," my grandfather told them in a stern voice, before reminding them that they were his friend's children. "And I'm not accustomed to pulling it out just to pull it out."

They put down their guns, but my grandfather knew they still held on to their anger. He warned Abel, who was headed to the makeshift bar under the mesquite tree, "Hijo, be very careful."

As soon as my uncle reached the bar, a group of about eight men gathered around him. My grandfather heard the firing of more than one gun. The women yelled, and men ran to the monte for refuge. The only man still standing was Abel, who had managed to fire his gun twice before collapsing. My grandfather shot three bullets, aiming at the two brothers. One fled into the screaming crowd and the other ran into the monte, hiding behind the mesquite trees.

My tío Abel breathed heavily, trying to speak, but only blood flowed from his mouth. People loaded him into the back seat of a car, where my grandfather cradled his son's head in his arms.

"When they came to give me the news, I see your grandfather completely covered in blood. He told me mi'jo was wounded," recalled my grandmother, crying like she usually did when she thought of her dead son. "But it was a lie, he was already dead inside the car. Mi'jo was already dead."

Abel died in his father's arms just before they crossed el arroyo Brazil on their way to the nearest hospital, a 45-minute drive to China, Nuevo León. The bullet, shot at close range, had nearly broken his right arm before piercing his lungs and heart.

"Apá's clothes were covered in blood, and he didn't want to take them off," recalled my tío Erasmo, the family's youngest son, who was eight at the time. "He walked around with the bloody shirt until the next afternoon."

My mother, seven months pregnant with my oldest sister, arrived with my father not long after her 30-year-old brother's lifeless body had been placed on the bare wooden planks of my grandmother's bed, while they nailed together his coffin. His blood dripped and settled into a thick puddle on the cement floor. His ears had already turned purple. Years later, after my mother had raised eight children and welcomed 17 grandchildren, she would recall that night, when sadness arrived at her childhood home and never left.

Hovering over her family, it watched through the years as my grandmother's body and will to live withered, and it fueled my grandfather's obsession with revenge.

At the Reynas' rancho, where Uelita Lola midwifed almost all of her eight children's children, my tío Abel's house was the first to grow quiet. His house was unlocked only on weekends or holidays when my tío Cleto's family came to visit.

Abel died before most of his nieces and nephews were born, but everyone knew of him, even those who were born decades after the day he was buried, the day my grandfather planted two pine trees by his gravesite. Only one pine tree survived and, today, anyone driving toward the cemetery can see the slim, pointy green top from afar. My uncle's sad story became Reyna family lore passed down from one generation to the next. But my grandfather hardly ever talks about that night.

Soon after her husband's death, Margarita miscarried their baby and left, leaving behind her house and furniture, their bed, her wedding dress.

My mother María Elva (right) runs into a long-lost relative at the cemetery during Día de los Muertos, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2003. At the height of its glory, the rancho hosted the biggest dance of the year on Day of the Dead. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

Chapter 3

Big-City Girl

My mother has her mother's small and delicate nose. And she has her father's sagging eyelids and his strong and stubborn ways.

She is the one who tells Uelito José María sus verdades, the truths our family has always preferred to ignore. Still, after my grandmother dies, he comes to live with her.

"If you don't want me here, I can go back to the rancho," Uelito José María says, usually after my mother has reminded him that she is no longer a little girl, he can't tell her what to do.

My grandfather is a picabuche, poking at my mother until she snaps.

"You should be grateful you had all those children in Mexico," she tells him in a voice armed with confidence, knowing my grandfather is another man, one who now admits his faults. "If you had had them in the United States, you would still be working to pay child support."

My grandfather says my mother's carácter fuerte, strong character, comes from his mother, Uelita Lola. One look at a pregnant woman's belly, and Uelita Lola, a midwife since she was 13, could tell whether the mother was carrying a boy or a girl. Uelita Lola was hardly ever wrong.

"My mother said your mother would be a man because of how she was sitting in the womb. She was upright," my grandfather tells me proudly. "Your mother wasn't a man, but she worked like one. She's fierce, she's a workhorse. You can't pick on her because she defends herself."

Four months before my mother was born, Uelita Cecilia's world dissolved into darkness: se oscureció.

In the spring of 1940, a violent thunderstorm pummeled northern Nuevo León. My grandmother Cecilia and her sister-in-law, Juanita Alaniz, were caught in the winds of a tornado as the two walked home.

They had spent the morning in La Lajilla, where they had gone to send a letter to my grandfather, who was in jail. It was a stupid thing, my grandfather says, to shoot at a passing car from the brush one afternoon as he and a friend hunted for quail to sell. They were arrested soon after and were kept locked up, even though my grandfather and his friend denied it.

Uelita Cecilia and her sister-in-law were halfway through the two-hour walk and still a ways from home when the storm caught them.

"It was horrible," recalls the now 85-year-old Juanita. "You could see the big cloud chasing after us. We were soaked, and we lost our shoes as we ran, trying to get away. We had to stop at someone's house so they could help us pluck the [mesquite and cactus] thorns from our feet and legs."

My grandmother believed the shocking fright, susto, if not prayed away, would later revisit in the form of sickness. Soon after the storm, my grandmother began experiencing sharp punzadas, pulsations, behind her eyes. Within a few months, she was blind. My grandmother was still blind when my mother was born in the fall of 1941.

No one remembers how long she remained blind, only that a healer from La Ceja helped cure her blindness. Still, for the rest of her life, my grandmother would blame that tornado for all her physical troubles.

Uelita Cecilia, shortly before her passing, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2003. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

El Río Bravo

Six months before Uelita Cecilia dies, weeks before her last winter, my mother and I take her back to Mexico. My grandmother hasn't been home in several months, but she has been begging her daughters to take her back. She doesn't want to die without seeing her rancho again. The doctor advises against travel, and my mother doubts her bladder is equipped for the journey. They compromise. My grandmother will wear a dreadful diaper. La Ceja is the only place Uelita Cecilia feels at home. In her own house, my grandmother no longer feels like an arrimada, a burden. From her kitchen table, where she used to eat alone, my grandmother directs us to dust the three bedrooms, sweep and mop the cement floors, and to make sure my grandfather has clean clothes: khaki pants, white muscle shirts, boxers, and blue and red paisley handkerchiefs.

My grandfather knows her death is hovering close. We know he knows by the quiver of his voice whenever he talks about Uelita Cecilia, su viejita. We wonder if Uelito José María feels guilty for the hard life he gave her.

She has already begun calling out to her dead: her firstborn Abel, her mother Goyita, her sister Juanita, who died decades ago, and for her father Plutarco, who died when she was only two, before she was old enough to memorize his face.

My grandmother made my mother promise not to bury her in the United States, away from her rancho, away from Abel.

"Even if you die in the middle of the night," my mother reassured her, "I will wrap you up in a blanket and put you in the truck and find someone to drive us back. We'll just pretend you're asleep when we cross the river."

As we cross the Rio Grande, my mother looks out the window at the water. The river has always scared my mother, always reminding her of the two times she crossed it, first as a child, then while she carried one in her womb 15 years later.

She was 11 when she first saw the Río Bravo in 1952. She waded across, the low water swallowing her small frame as the rocks dug into her tender, naked feet. This was the first time she made her trek north, to el otro lado, where she imagined a life so different from the one she knew—big fancy houses and all the honey and white bread she could eat.

Uelito José María and his children - Abel, 16; Lupe, 14, who was always so sickly; my mother; and José, 8—crossed the river at Los Ébanos, where they waited for my grandfather's brother-in-law, Juanita's husband, to pick them up. They would spend the night in their house in Edinburg, two hours from their final destination, the King Ranch. The ranch, the largest in the state, is a legend among Mexican workers, who still tell stories about picking cotton there. Uelita Cecilia had stayed behind in La Ceja with half the family: 12-year-old Ofilia, 6-year-old Ernesto, and Cleto, just a few days old.

My tía Juanita took in all the members of the family: pregnant women, nieces and nephews, brothers and sisters. Juanita and her sisters, Rosario and Jacinta, left La Ceja soon after they married, as soon as they could. Their children, unlike my mother, learned to speak English, and the distance between them and their rancho grew. Before long, they stopped coming to La Ceja.

Uelito José María vowed to never leave, even when everyone else left.

"A los gringos, ni los huesos," he would say. To the gringos, not even my bones.

Juanita, who had witnessed the tornado with my grandmother, was the first Reyna from our rancho to leave. She would always live in Edinburg, not far from the cabbage, onion, and carrot fields she used to pick with her children. Until recently, Juanita competed in and won senior-citizen center beauty pageants, where she took turns dancing with different partners. It took open-heart surgery five years ago to make her retire her beloved high heels.

My mother has always adored her tía Juanita for taking her and her family in during their first days in the United States. Years later, when we would visit Tía Juanita, my father would slip her a $20 bill, still grateful for her generosity toward my mother.

My mother first picked algodón, cotton, in northern Mexico, in the labores of Tamaulipas and Nuevo León. The work on the outskirts of Matamoros, Doctor Coss, and Camargo lured entire families from the ranchos, where home was a small patch of dirt under tin roofs surrounded by algodón. Women arrived with their tiliches, belongings, including their molinos and metates to grind corn for tortillas.

“Mexican girl, carrot worker[s],” Edinburg, Texas, 1939. Photo: Russell Lee. Source: Library of Congress

But at the King Ranch, my grandfather and the other wifeless men with children cooked the pinto beans and atole that they carried with them to the fields. At night, my grandfather fed his kids before putting them to sleep.

From inside the tent, as my mother rested her head on a pillow she had stuffed with cotton she had picked, she could hear wild turkeys calling and the songs of the chicharras. She could hear families in tents around hers, platicando, chatting, and teenage boys calling each other by women's names. ¡Oye, Florindaaa! Like a far-away dream, my mother could hear men yelling and laughing, playing poker while they smoked and drank. She imagined her father there.

My mother remembers seeing my father working alongside his brother Rafael. My father was 16 and didn't notice my mother, who was five years younger.

There were mothers with children and motherless children. The women bathed and washed clothes in a brook near the encampment.

"Era muchísima gente," my mother says. "Too many people and tents everywhere." My mother and her aunts would watch the white women walk past them, unaware of the Mexicans who blended into the cotton fields. "My tía Ramona had never seen americanas," recalls my mother, laughing. "They were wearing shorts. Tía Ramona was shocked. She said, 'Why aren't they wearing any clothes?'"

My mother and her brother Abel were my grandfather's two strongest manos, hands that tore swiftly through surcos of cotton even when the dry buds tore into their fingertips. My mother came to the United States sin papeles twice and was deported once.

"I remember the day the migra came," my mother says. "It was a Monday. We had just bought groceries the day before. All the tents were stocked with food. They arrested all the families except for one. That family didn't have papeles, either, but they spoke English. They deported us through Matamoros, and we spent the night sleeping outside by a chicken coop."

All those who had children were deported through Matamoros, across from Brownsville, which was a shorter trip back to La Ceja. My grandfather and others, including those who had hastily borrowed children from sympathetic Mexicans to present as their own before la migra, were gathered into trucks that dropped them off in Brownsville, by the international bridge, then were watched as they walked back to Mexico.

The teenage boys and men without children were transported in truckloads to Eagle Pass, across from Piedras Negras, Coahuila. After my father was deported, he spent a few days in Piedras Negras, washing dishes at a restaurant to pay for his trip back to his rancho.

My mother María Elva at the rancho, Nuevo León, Mexico, 2004. She begged my grandfather José María to let her move away. "Apá used to say that a woman's job was in the kitchen. Only men could study," my mother says, her voice trembling with anger. She finally left the ranchos when she was 17 and returned a couple of years later. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

Big-City Dreams

When my own mother dies we will bury her back in Mexico, near La Ceja, the place she was so eager to leave when she was a young girl.

She wanted to live in la ciudad, where girls wore red lipstick and their skin looked like porcelana, porcelain. Soft heels. Long nails. Silky hair. There would be jobs, electricity and el cine, where she could watch Pedro Infante movies.

"Yo quería ser alguien," my mother says. "I wanted to be someone."

There were some 30 students at her school in La Ceja, where Uelita Cecilia's brother taught grades 1 through 5. My mother was better with numbers than with words. As the chorus of children chanted the multiplication tables—cuatro por cuatro, 16; cuatro por cinco, 20, cuatro por seis, 24—my mother yelled the loudest until her raspy voice was the only sound she could hear.

And when her teacher, her tío Chonito, read to the students, my mother didn't always listen to what he was saying. It was how he said it that mattered. He spoke like an educated man, tan bonito.

On the inner walls of the school, her tío Chonito sketched the faces of Mexico's presidents. El Indio Benito Juárez, who's been called the Abraham Lincoln of Mexico, was my mother's favorite. She memorized fragments of Juárez's speeches, and, years later, she would recite them to her children as if quoting the Bible.

While her younger brother Ernesto begged his father to let him quit school to build up his own goat pen, my mother re-enrolled in fifth grade. She wanted to be a nurse or a seamstress.

She dreamed of trips to Monterrey, the big city where girls from the rancho hardly ever went to study and only got to visit if their husbands could afford to take them there on their honeymoons. The trip was more of a reward for the virtuous women who left their childhood homes dressed in white and with their parents' blessing.

My mother begged my grandfather to let her move away. Le rogó. But my grandfather refused. He heard city girls were loose.

"Apá used to say that a woman's job was in the kitchen. Only men could study," my mother says, her voice trembling with anger. "A woman had no business studying. He told me, 'I already gave you girls enough education to defend yourselves and write your names.'

"Every time I think about it, I feel all this rage. But I tell myself I shouldn't be angry. Your grandfather is an old man, and his time is short."

My mother finally left the ranchos when she was 17. She ended up in Peña Blanca, a dusty stop south on Carretera 33, the road to Monterrey. A distant relative hired her to keep the house clean, starch and iron shirts.

A couple of years later, she returned to the rancho. She met my father when she was 20. A few months into their relationship, my father gave my mother her first pair of stockings and a thin, gauzy red pañoleta, a scarf with a smooth, expensive feel. She knew it had to be from the United States.

My parents saw each other only at the rare dance that my mother was allowed to attend. Back then, most fathers did not allow their daughters to speak with their dance partners, much less dance two songs in a row. As they danced, my parents would secretly slip each other love letters.

My mother describes her dancing days with such gusto that you would never think she was such a devout Christian. I once asked her, if she had to, who would she pick, God or my father? God, she said without hesitation. She was insulted I even asked.

My father Gumaro, who grew up in El Puente, a nearby rancho, was handsome and maduro. Era flaco, a slender man with a thin mustache and those ojos borrados that earned him the nickname El Gato, the cat. Green eyes que alborotaban, that captivated—a gift from his Spanish blood, my father would often say. He was trabajador, hardworking–and, really, that was all that mattered.

My father's hands felt like sandpaper. When he would pat our heads, our hair would get caught in the dried cuts on his manitas. My cousin Eloy, my father's brother's son and an electrician in Austin, has my father's hands. He was an extra, a Mexican soldier, on the set of the most recent remake of The Alamo (2004). There is a close-up in the movie of his worn hands loading a cannon.

My grandfather rejected all of my mother's suitors. One was too stingy. Another was a womanizer by association (the man's relatives were all mujeriegos, my grandfather insisted).

"Apá couldn't see his own tail, which was longer than a freight train," my mother says, referring to my abuelo's own hotel heart. "He found flaws in everyone else, but there was no one who pointed to his flaws. That's why they called him the king without the crown." When my father asked for my mother's hand in marriage, my grandfather asked him to wait one year, as was customary.

So, one Saturday night, in March 1961, as Los Hermanos Flores played at a dance held on the school grounds, my mother ran off with my father.

"Your father didn't want to wait. He wanted it fast, and so did I," my mother says. "I wanted another life."

Not long after they walked into the darkness, the gossipy whispers began: Elva, la de José María y Gumaro, eloped. And before the dance was over, Los Hermanos Flores played "El gavilán pollero," the [1951 Pedro Infante] song they played every time someone eloped from a dance.

Gavilán, gavilán, gavilán

Te llevaste a la polla que más quiero.

Si tu vuelves mi polla para acá

Yo te doy todito el gallinero.

Sparrow hawk, sparrow hawk, sparrow hawk

You took the young hen I most loved.

If you bring back my young hen

I'll give you my entire chicken coop.

By then, there was hardly any work left on the ranchos. So my parents spent their honeymoon months picking corn in Río Bravo, Tamaulipas, before heading to Reynosa to take care of a chicken farm, just two months before my oldest brother was born.

By the time my mother gave birth to her second child in 1964, she was back in El Puente with her in-laws, and my father was working in Dallas.

By the 1960s, most of my mother's generation began looking north, and pregnant women were coming to the United States, where they hoped to give birth to their American babies. A baby born on U.S. soil would be a citizen even if the parents had crossed the Rio Grande sin papeles.

One month after my mother buried her brother Abel in 1966, she left for the United States for the second time in her life. Eight months pregnant, she arrived in Edinburg to stay with her tía Juanita again, who took her in for a month while my father was back on the rancho, cutting fence posts to pay for the birth of their third baby. In Edinburg, my mother spent her days sewing baby clothes, waiting for my oldest sister, la first americana, to arrive.

Empty swings in nearby Dr. Coss, the biggest town and namesake of the municipio, Nuevo León, Mexico. Photo: Delcia López / San Antonio Express-News

Chapter 4

Only the Dead Return

My mother often threatened to disappear—either back to the rancho or on the day of the Rapture.

She reminded us of her plans, especially on those long, tired days when nobody seemed to appreciate that she washed and cooked for a family of ten.

"The day will come when I will leave this place. One day you won't find me," she told us in her melodramatic Mexican telenovela tone. "Then you will realize how much you need me."

My parents always spoke of one day going back to Mexico, where they imagined a much simpler life.

They planned to grow old by the arroyo that slices through the 45 acres my parents bought near La Ceja in 1974, their first big purchase.

My mother would raise chickens, goats, and maybe even a couple of pigs. My father would plant his sorghum, melons, and calabazitas and roam his own fields, the ones he ignored all the years he worked someone else's.

There were others who also planned to return. My parents' compadres Hermelinda and Eugenio Treviño were the only ones who actually left La Joya for La Ceja, but after a handful of years, they changed their minds and came back. No one has moved back since.

Only the dead or deported return.

Life in that corner of Nuevo León hasn't been the same since the 1970s, when young families who couldn't find work finally left.

A few families moved to nearby towns in Tamaulipas, like Ochoa and Comales, and some relocated farther south to Monterrey. Most went north to Texas, where they settled in towns along the border—Weslaco, Edinburg, McAllen, Rio Grande City, and Roma, among others.

The largest concentration—Los Hernández, Los Treviño, Los Salinas, Los Reyna—ended up in La Joya, just three miles north of the Rio Grande. Brothers and sisters, nephews and aunts bought property next to one another, separated only by a chain-link fence or a dirt callejón, an alley. Your best friends were your cousins.

By the time I was born in 1974, my parents and siblings were renting their first American home, a $15-a-month cardboard shack on 11th Street in La Joya. By then, my parents had been legal residents for several years.

Two years later, my parents bought a lot on the corner of Sixth and Leo J. Leo Avenue, named after the small town's largest character, a staunch Democrat, de hueso colorado. The mayor was the patriarch of the Leo clan, which has intermittently run the town of 2,500 since 1961.

Most of the residents already there were Mexican Americans, lifelong Tejanos, who, as they say, never crossed the border—the border crossed them.

Recent arrivals were easy to spot. Our houses were always locked up for the summer while we lived on the road, chasing harvests from state to state. As early as late March, a caravan of cars carrying people from the same ranchos crossed state lines, day and night, on their way to labor camps and sagging barracks in Colorado, California, West Texas, Florida, and South Carolina.

In Shafter, Calif., outside Bakersfield, we lived in a labor camp with about 100 houses, where everyone was either related or conocidos, family friends. At night, after their showers, people gathered on the front steps of their houses or sat on the tailgates of their pickups in the backyard. Swapping stories for hours—as they had always done back in Mexico—they sharpened their hoes, filled their coolers with water and ice, and loaded the trucks. Back then, my mother says, women weren't afraid of hard work, they were tough. Aguantaban mucho.

My mother María Elva collecting leña, Nuevo León, Mexico, sometime after 2004. The cartel turf war may not be over, but for now it is quiet. So she'll hitch a ride south with a sibling, pay for their gas and meals. She wants to collect wood, cook in la chimenea. Forget that most of her loved ones are dying or dead. Photo: Macarena Hernández

When there was no more work, we would move north. In Parlier, we picked grapes and laid them, still on their vines, on large pieces of butcher paper on the sand. A few weeks later, after the grapes were dry, we turned them over to make sure they became raisins.

It was in California that I first learned of César Chávez, who fought for migrant workers' rights. But my parents never thought of joining the picket lines; they had too many children to feed.

We hoed cotton fields throughout West Texas. The days were long and the surcos, rows, eternal. I hated working in the fields. I often begged my father to let me sleep underneath the cotton plants or in our van, especially after the lunch break, when the sun burned hottest. I could sleep anywhere I found enough shade for my face. I took frequent water breaks, always trailing behind everyone. Most days, my mother worked behind me, cleaning up after my half-hearted efforts.

In Colorado we lived outside Commerce City, in tired wooden barracks. Through the kitchen's tiny single window, we could see the parsley fields we picked and the rumbling Santa Fe train.

"One of these days, I will disappear. I will jump on one of those trains and you will never see me again," my mother would tell us. "I will go somewhere where no one will know my name."

My family picked cucumbers and tomatoes in South Carolina, in a segregated labor camp in the middle of what I remember as a fairytale-like forest with tall, old pine trees.

During the day, Mexicans and Blacks worked together. At night, we returned to our own side, opposite the communal bathroom and shower. The only time we crossed that invisible boundary was to retrieve a ball we had kicked too far.

After my older sister Veronica eloped, I was the one my father would load into the van and drive from farm to farm, looking for work. Less than four feet tall and nine years old at the time, I stood between my father and the rancher, translating for two grown men who could only smile politely at each other. I didn't like to see my father, a proud and handsome man, beg with smiles.

In the fourth grade, I was placed in a gifted-and-talented class in La Joya, where most of my classmates came from English-speaking homes. Their parents never missed a school function.

I shared a double desk with another Mexican-American girl who lived on my block. I hardly knew her. Her father was a teacher and her mother a school administrator. They lived in the only brick house in the neighborhood, and the only one with air conditioning. Her father jogged around our block every afternoon. The other men, including my father, wondered why anyone would want to sweat on purpose.

Once, my deskmate pointed to a large bug crawling on the desk. "Ugh," she said, laughing and pointing at me, "that bug fell out of her hair!"

I knew the bug was too big to be a piojo, a louse. But I cried, anyway.

In middle school, I began to wonder where I belonged. At school, I spent my days in English, returning to my Spanish after the last bell rang: What am I? Mexican? American? Both? Neither?

In Mexico, I am a pocha, an agringada, Americanized and less mexicana. I'm from el otro lado, from the United States, where women are arrastradas, lazy, and where you won't find one that still makes tortillas every day—if they make them at all. In the United States, I'm a hyphenated American, an arrimada, someone who doesn't always belong, even though I was born north of the Rio Grande, in Roma, Texas.

Only in La Ceja did I feel like I belonged.

Presenting at a Write to Change the World seminar, led by the OpEd Project, Simmons College, Boston, MA, 2016. Photo: Mary E. Cronin/The Byline Blog

Generational Conflict

Between harvests, my father followed construction sites from state to state, while my mother stayed behind in La Joya with us. My father constructed buildings and paved parking lots throughout Texas, Florida, and Mississippi. He supervised construction crews of mostly relatives, including his sons, his cousins, and their sons. He was thrifty and never drove past plastic bags littered along the highway shoulders or a good deal at the flea market.

He came home whenever he could and brought his daughters piggy banks, fat with spare change. My three sisters would hang adoringly like leaves from his limbs.

My father was a strict man, especially when it came to his daughters. He and I argued about everything from Mexican politics to the length of my skirts. I was in high school the first time I remember my father asking me for my opinion. I don't remember what my father asked, only that he asked me. We were driving along a highway overpass in Mission that looks toward Foy's supermarket and the old M. Rivas grocery store, where I got lost when I was five.

The only argument I vividly remember took place one night in the late spring of my senior year in high school. I was 17. I had been accepted to Baylor University and needed to attend orientation.

"Why are you going so far to find a husband?" my father asked when I told him I wanted to go to college in Waco, seven hours north of our hometown. He then gave me the same advice he gave my sisters: get a carrerita, a vocational career, something short and inexpensive.

"I am going to go to college," I told him defiantly, pointing my finger at him. "And I am going to graduate, and when I'm 24 years old and still single, I don't want you asking me why I'm not married."

I had planned my escape since middle school, when I had written notes to myself, which included reminders to stay away from boys and move away to college. Stored in my brown vinyl box, the only place in my house that felt like my own, I kept the simple instructions secreted away.

I longed to experience the world and dreamed of moving away as far as I could. I was luckier than my brothers and sisters, who spent their high school summers working the fields. By the time I was a sophomore in high school, my family stopped migrating. My brothers had found work in construction, and my two older sisters had graduated with vocational careers in medicine.

Before I left for college in the summer of 1992, my grandmother Uelita Cecilia gave me her blessing and her advice: to take care of the one thing Mexican mothers and men most highly value, a woman's virtue, her virginity.

"Cuídate ese pedacito," she said, smiling. "Vale oro molido." Guard that little piece of you. It's worth gold.

On that summer day in June, as my parents drove me north to Waco, I cried until we reached Falfurrias an hour later. I knew my father wanted the best for me; we just had a different idea of what that should be.

My father spent my first year of college sentido, hurt that I had left without his approval. When I called and he answered, he kept the conversation short, quickly handing the phone to my mother. Years later, after his death, my mother told me she had persuaded him to set me free.

My three sisters left my parents' home when they got married - at 17, 18, and 22—the only way a woman in my family was allowed to leave. When my sisters got married, my father gave each one $1,000.

It's not that my father was eager to marry us off, it's just that he thought it was inevitable. Once wed, we were harina de otro costal, flour from another sack.

My brothers, on the other hand, led lives without boundaries. They smoked cigarettes, drank beer, and stole kisses from their girlfriends in the backyard. My father spent a lifetime teaching them how to put a roof over their heads, literally, and encouraged them to buy lots to build their families a home.

When we share an honest plática, usually talking for hours late at night, my mother tells me she never thought she'd grow old alone. I know she still prays for a fourth son-in-law.

Men are machistas, I tell her, especially mexicanos and Mexican Americans, whom I love but I think have a hard time loving women like me.

"They slowly lose their machismo, hija," she says. "Your father was very machista, and little by little, he lost it. They begin to understand that, in this day and age, and life in the United States, it's different. They begin to understand that a marriage is made along the way. That's when your love is really tested."

My father has been buried in the Sara Flores Cemetery in Nuevo León, Mexico since 1998—a few feet from his parents' graves and his beloved grandmother Manuela, and next to his younger brother Enrique, who had also died in a car accident nine years earlier. The blank granite marks where my mother's grave awaits. Photo: Macarena Hernández

Death and More Death

Mexicans are obsessed with death.

"If you don't bury me en el rancho, I will come back after I die and pull your feet in the middle of the night," my mother told us. She would remind us to take her back to Mexico, especially around the first two days of November, when we celebrate Día de los Muertos.

On the Day of the Dead, the cemetery in the rancho fills with people, most of whom haven't visited all year.

The first time I discussed death with my mother, I was five and my pet chicken had just died. My mother was raising a dozen of them in our La Joya back yard, which was infested with fire ants.

I found my black hen lying flat and stiff underneath my mother's washing machine outside our house, not long after she had sprinkled ant poison that resembled chicken feed. I cried for days.

My mother reassured me that my nameless chicken was in heaven. But I kept crying.

"Por favor, Macarena!" she told me. "Please leave those tears for the day I die. When I die, there will be no tears left for me."

Every year, around Day of the Dead, my parents also visited my brother Ramiro's gravesite at La Piedad cemetery in McAllen. They would tie a small bouquet of plastic flowers to the green metal nameplate marking his grave.

They never bought him a marble headstone, because they didn't intend for him to stay there.

Ramiro, my mother's seventh child, arrived in early November 1971 while my father was working back in Mexico and my mother was at a relative's house in McAllen. My tío Baldo and tía Queta rushed my mother to a Mission clinic when her contractions came. When the clinic staff turned her away, my mother’s relatives drove her to Starr County, 35 miles west of Mission.