La Buddhalupana Way

Journalist Macarena Hernández interviews celebrated author Sandra Cisneros

Photo of exhibition installation Sandra Cisneros: A House of Her Own, held February 15- July 1, 2017 at The Wittliff Collections, Texas State University, San Marcos, TX. Journalist Macarena Hernández presented during the inaugural symposium to celebrate the launch of the exhibit, which highlighted key artifacts from the Wittliff Collections’ “Sandra Cisneros Papers, 1954-2014.”

AUTHOR’S NOTE

Sandra Cisneros and I met not long after we had both lost our fathers. Our first conversation was all about our grief. Her father died in 1997; my father died the following year.

I wanted to know what had helped her navigate that feeling of breathing underwater when someone dies. Sandra, the only girl in a family of seven, was her father’s consentida. I, one of four girls, in a family of eight was far from that.

When I met her through our incredible mutual friend - la amazing Chicana feminism pioneer de Norma Alarcón, founder of Third Woman Press – I was a young reporter at the San Antonio Express-News, and Sandra was in the last stages of copy edits for Caramelo (Knopf 2003), a novel she had worked on for nine years. She had lost her father to cancer during that time, a year before my father died in a car accident.

Sandra, who has rescued so many animals, mostly dogs, also rescues writers. So many of us young writers - many of us first-generation writers, college graduates – have benefited from her founding of the Macondo Writers Workshop, which meets annually and is community to many writers throughout the country.

This interview excerpt, which was edited for clarity and length, is from conversations we had a year into the 2020 pandemic. We talked about growing up in Chicago and her time in Texas; the educational journey that led her to the Iowa Writers' Workshop; and about her spiritual teachers, including Thich Nhat Hanh and Pema Chödrön.

–Macarena Hernández

September 2023

Early Inspirations

Macarena: I always describe your writing as gorgeous. You have a way of combining your metaphors, your similes, a way of putting words or things together that you normally wouldn't. I always think about that description of “tears in your throat” or just the way you really turn a phrase. It’s what you find in your novels, in your short stories, in your essays: these ways of seeing the world so differently. They’re kind of childlike and inocente and just a beautiful prism. So you started writing in sixth grade–when did you start developing that eye and that ear?

Sandra: I think we’ve had that eye before we learn how to read and write. I think we have that when we’re children, when we’re still manipulating crayons, before we even have the motor skills to pick up a pencil. I think we’re making comparisons and noticing things. I remember noticing things and paying attention to tiny details. I remember going to school with [my brother] Kiki, and Kiki taught me how to be visual. Maybe I was always visual, but he and I were the visual artists. But he was the one. We were trained to take care of the one beneath us because there were so many of us. Like the champagne glasses and the pyramid, that you pour the one on top and the ones on top take care of the one under it. Well, it was like that: My oldest brother was responsible for all six of us, and Kiki was responsible for all five of us. So Kiki was especially responsible for me, so I learned how to tie my shoes and how to ride a bike from Kiki. He was the one who accompanied me to school on my first day, with my mother, but he taught me how to go home in case he was sick. And so, I had to learn and memorize the route, and he would show me things like how to cross the street with the light, where to turn: “Notice the house that has little gold stars painted on the ceiling of its porch? See that house? Okay, that’s where you make a right here, you go here…” So I learned to pay attention to little details, and it was very magical being with Kiki. Like, we wouldn’t just go to school and go in through the gate. No! We would go in through two iron bars that someone had bent open like this, and we’d walk through there and say, “Okay, let’s pretend we’re getting on the bus.” “Okay!” And it was all a game and a great sense of play. I think that’s how artists begin, how they’re always seeing things that aren’t there, like we saw “bus” instead of just some bent bars. We noticed people, like, “How come that crossing guard lady, she doesn’t have any flowers? Let’s bring her some! She doesn’t have any!” “Oh yeah, okay!” We were always paying attention to people and architectural elements and transforming everyday things into things that were very magical. That's what I remember about being with Kiki, whereas with my oldest brother, he was absent for a year, maybe longer. He went to school in Mexico, for military school which indelibly marked our lives, but he never walked to school with us. He ran ahead. And I think those moments when I was alone with a brother, who was an artist—and is an artist still—was part of enriching my way of seeing reality.

Macarena: And Kiki was instrumental. He was your partner, your fellow artista, your companion. You guys were hosting events together in Chicago. Can you talk a little bit about that?

Sandra: Well, Kiki had the money, because he didn’t go into the arts; he went into business administration, and he had money to get a nice loft apartment when he was young, whereas we were all just struggling along on minimum wage. When we saw his loft over in South Loop, we said, “Wow! This would be a great space for poetry reading and art exhibits.” It was us – me and Carlos Cumpián and people who realized the potential. Kiki’s loft looked like some hipster vodka ad, with all these young people of all different colors, and we thought, “Ah! With this, we could have a poetry reading here.” So we asked him and, basically, it was our initiative and his curating, because he would select the visual artists, and we’d select the writers. We would have, like, two or three writers a month and maybe one or two visual artists whose exhibits were there. I think we charged something or maybe we only had a cash bar or donations. It was very rudimentary. We never made any money because we weren’t thinking about money. We never thought about money, we just had a great time. We would put the series on, and it was fun! And it was the first time that you would have artists who maybe didn't have a venue to show in the White galleries. And the readings were so tribal in Chicago, so it was a nice, neutral space, where people from different parts of town could come centrally to downtown at night—which was dead—and have a place where all colors could come together. It was really multicultural before that word existed. It was very amazing and beautiful. I remember my mother and Licha’s mom—my aunt Margaret—came, and I remember I was sitting in the back—someone was reading—and my mother leaned back and said to her sister, “Have you ever been to anything like this?” And my aunt said, “No!” And my mother said, “It’s nice, right?” And I was really happy that they could enjoy it, could enjoy the writers, could enjoy the art. And what my mom liked is that you could have a highball, you know, a little cocktail. Anything to get out of the house and have a cocktail! So that was nice and, plus, everybody got all dressed up, and we had drinks and it was just like I said: like some fancy hipster ad but with people of color before people of color would unite. They never thought of that when they did these ads; this was very early, we’re talking like 1980. So it became a venue –because it was in Central Chicago–for people from all the neighborhoods to cross the border and come together and perform and showcase themselves.

Nezahualcóyotl Poetry Festival, Mexican Fine Arts Center Museum, Pilsen, Chicago, 1991. Gelatin silver photograph; 5 5/8" x 8 1/2". Top row: Carlos Cumpían, Luis Rodriguez, Raúl Niño (Chicago), Ray González (Texas), Juan Felipe Herrera (Califas), Rosa María Arenas (Michigan), José Montalvo (Texas). Middle row: Demetrio Martínez (Missouri), Evangelina Vigil (Texas), Raúl Salinas (Texas). Bottom Row: Trinidad Sanchez (Michigan), Sandra Cisneros, Carlos Cortéz (Chicago). Photo: Jeffrey D. Scott. Source: National Museum of Mexican Art

Higher Education

Macarena: And then college and graduate school—how did they shape you into becoming a writer? And the people you met during that period of your life?

Sandra: I have very few friends from my Iowa [Writers' Workshop] days. I had a handful of people that I can name on one hand. Basically, it was Dennis Mathis, who is still my friend, and Paul Alexander, a poetry workshopper who is still my friend. I had Jeffrey Abrahams, who is still my friend, Mary Jane White, who is still my friend, Joy Harjo and some other people were friends, like Michael Simms, who runs a press out in Pennsylvania somewhere. But they were very fragile friendships. Some of them, they were friends when they were, and it would be many years later that we’d see each other again. The one who continued and was a constant is Dennis. And he wasn't even in the poetry workshop, he was in the fiction workshop. I felt as if, when I would visit his workshop, I felt comfortable. And I wondered, did I apply for the wrong workshop?

Macarena: Did you? How do you feel about that now?

Sandra: No, I think I did the right thing because the fiction workshop, if I had taken the fiction classes, I would write differently. So they didn’t touch my fiction because they never saw it. Dennis was my fiction tutor, in a way. And the poetry I had to write, I wrote a resistance to the poetry workshop and to what was being written around me. I had a couple friends who I think weren’t writing like that, who had a different type of a voice. But basically, being in the poetry workshop shut me down. It caused me to have to search for it and discover my voice, because I had to think about, “What could I write about that isn't like anyone else’s, and how can I write about it that doesn't sound like anyone in this classroom?” That’s how I discovered the voice for The House on Mango Street (Arte Público Press, 1984), but that’s all documented in my introduction. [The poetry workshop] just was a negative experience that turned out to be wonderful, but I also had resources in Iowa; I tell people that, if the [Iowa Writers' Workshop] program doesn't work, make sure there are other resources there. Make sure you can go to lectures and other art forms. For me it was a saving grace to have the art museum and art-history classes that I took, to be able to afford to go to the auditorium and see Merce Cunningham, Paul Taylor dancers – you know, the things that I couldn’t afford to do, I could afford when I was there. And the other thing, it gave me the liberty to go out at night by myself, something I couldn't have done in Chicago. So I was really relieved that there was a bus system up to a certain hour, that I could go and take the bus back to where I lived. It made me feel safer than if I had been trying to discover these things if I had gone to a big city like New York. Things were affordable and safer. There were many things about Iowa City that I enjoyed, and I had to separate Iowa—the [Iowa Writers' Workshop]—from University of Iowa and Iowa City, which were nurturing to me.

Macarena: Have you sorted that out over time? Because I know about your experience in Iowa—and you’ve talked about it extensively, how you felt out of place. A lot of higher-ed institutions, they’re not fertile spaces for young people of color, at times.

Sandra: I just felt more at home everywhere except in the poetry workshop. Everywhere except there. I also made friends with people in the art department. I felt really happy taking dance. I took ballet, I always wanted to take ballet, and I had taken it as an undergraduate. It was just fun to be in ballet class; it was the only phys-ed class I liked. I took art history, and I met visual artists, and I went to concerts at the art museum. You know, small concerts that were in a small, intimate space, as well as going to the auditorium and going to see dance/dancers. I should've done more, but I think I was always frightened that I wasn't writing and not going to get my thesis done. It was a very enriching period. I remember once falling asleep on the banks of the Iowa River, and I could never have done that in Chicago: to take a nap on the grass and just be there? It was just the newest and boldest thing that I had done, [taking] a nap outside under the tree by the river. Imagine! In Chicago! Somebody could have stolen or violated you, or you could have met a rat, and I didn't have to worry about that. It was so cool. I felt so happy, I felt like I was a character out of a novel. I thought I was Alice in Wonderland or Rip Van Winkle. It seems so remarkable.

Macarena: I can imagine how stress-free and relaxed your body must have been—and your psyche—to say, “I’m just going to disappear into my sleep here by the river.”

Sandra: I felt really happy. And I remember that time when I took that nap, that I thought, “Wow!” This was the very beginning of my stay. I said, “I could get on a bus and disappear and no one would know where I went.” And some part of me wanted to do that. It was some part of me that just wanted to leave all my troubles and go away and just disappear.

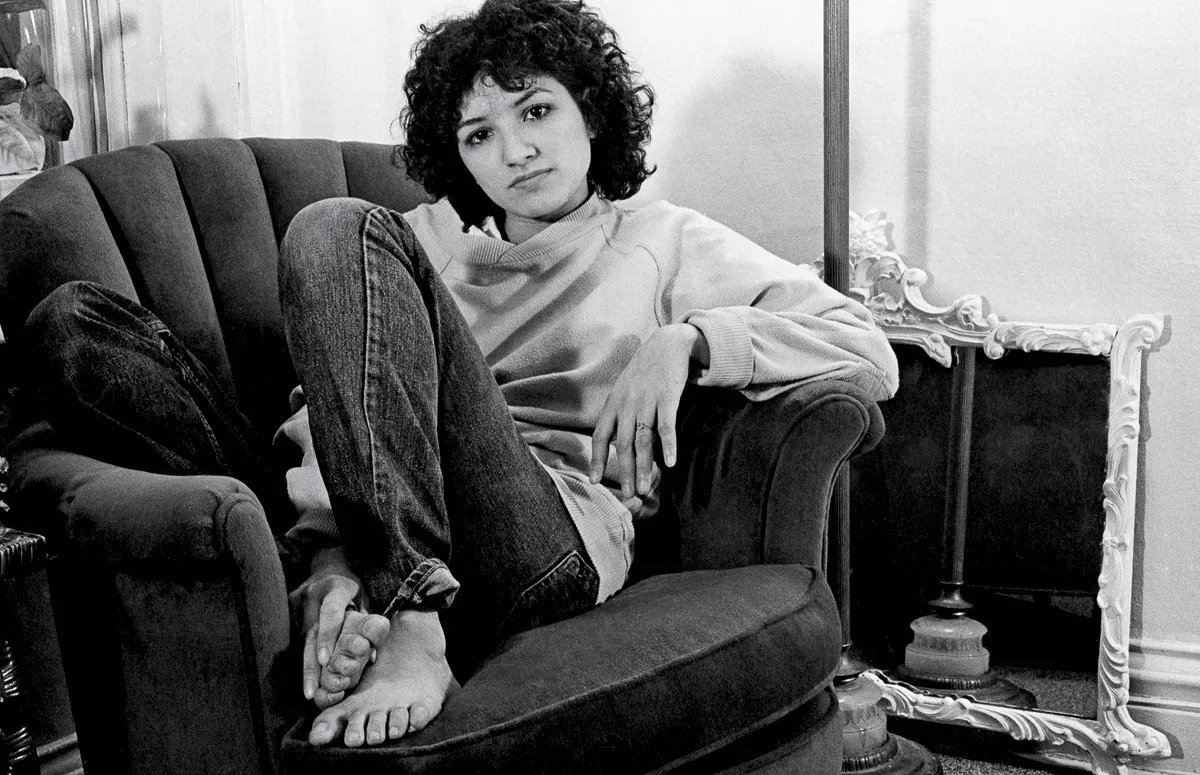

Sandra Cisneros in Chicago, 1981. Photo: Diana Solis, courtesy of Sandra Cisneros

Chicago

Macarena: I just kinda want to take the reader through your early path. Shortly after Iowa but before San Antonio…

Sandra: From Iowa, I went to Chicago. I went on Friday, I finished my semester, and then on Monday, I had a job that I had arranged for. It was a minimum-wage, part-time job, but it was a job nonetheless. So there was no rest for me. I went directly to work, and that’s when I was working for Latino Youth [Alternative High School] for, what, three years? Three and a half years? Starting part-time as a teacher, with two courses in Spanish for Spanish speakers and remedial reading, I think. Eventually, I would end up being an interim director, which was kind of wild. I was an interim director while they were searching for someone. I think they just put me there, because they thought they could manipulate me.

Macarena: Is that when you got your first apartment on your own?

Sandra: Yes, first I lived in my father’s building with my older brother, and then I got my own apartment. But I was teaching and living in that basement apartment for a while. I remember living in that basement apartment before I moved.

Macarena: And so, after that…

Sandra: After Latino Youth, I went to Loyola University, my alma mater, and I didn’t teach. I worked as a counselor for the Educational Opportunity Program, which was a program that helped to admit students of color, the at-risk students who normally wouldn't be placed at the university, to create diversity. It was a diversity office, and I worked with basically a Black staff and their hiring of me was – I was one of two non-Black staff [members] in this building– to create a more diverse freshman class. It was great. It was very different from any place I’d ever worked. I had been working mainly with Chicanos, not exclusively, in the last place [I worked]. So to be in a Black environment was a whole different energía, and it was just joyous.

Macarena: Thank you for taking us through your early years. I thought some of the origin story would be good to record here. You’ve done a lot for libraries and museums. You are also a collector and often donate, too. The Museum of Mexican Art in Chicago has been the benefactor of a lot of work that you’ve collected and donated. I wondered how this started.

Sandra: Well, you have to realize that I earn from my pen so [that] I can buy art. I didn't start out thinking, “I could buy art.” I know artists, and a lot of times, they were painting something on an easel, and I would say, “Well, how much is that?” And I actually could afford it. Maybe not all at once, so I would buy things poco a poco [little by little]. I started buying art and becoming an art collector very young, even before I started earning. Once I started earning, I found out that I could donate things and make a tax deduction and, once I had to pay a lot of taxes because I started earning, I’d rather donate and help an artist than pay for bombs. Wouldn’t you? It seems like a no-brainer. One, if I wanna keep something, that’s fine in my lifetime, then I can donate it. But if I also see an artist who's doing work I like, and if a museum would like to have that piece, it’s within my reach now that I can buy it and donate it to them and help the museum and help the artist. And that makes me so happy! I’m a connector! I’ve always been a connector. I get delighted just introducing you to some other friend that I like. So if I’m doing that, it’s just the same thing I’ve always done – introducing this artist to this museum.

San Antonio

Macarena: Texas seems to loom big in your writing, at least until before you went to Mexico. What would you say about Texas as a muse or as a place where you found stories? How did it change you as a writer or influence you as a storyteller?

Sandra: I think I was a little shocked when I got there at how behind the times Texas was with women’s role and place in society. And even now, it’s even worse, with everything that’s happening [today] with women [losing the right to] control their own bodies. But when I came in 1984, I really had just come from living abroad and traveling and feeling very independent. And then I came into a community where I felt women were harassed. I was harassed riding to work on my bike. I was harassed with the people I worked with. I just felt like I was treated like some substandard citizen by my own raza. It was very shocking to me. Things that seemed normal to people in Texas were shocking to me. It was very provincial. I remember sitting after work at an icehouse—I don't know why I hung out with the people I worked with, since I didn't like them, but maybe I was trying to get them to like me—and we were having beers, and we heard some shots, and the next thing we see is an ambulance across the street—at a little icehouse across the street on South Alamo—taking a body away. We watched the news…a woman [had been] shot by a man, [who] said he had to shoot because she was armed – she came at him with a mop. I thought, “Where am I?” And I put it in the story “Woman Hollering [Creek],” the title story [of Woman Hollering Creek and Other Stories (Random House, 1991)]. Things like that happened, a lot of stories of violence. It was sort of appalling to me that I wound up weaving [the shooting] in. The very first opportunity, when I was invited to write about Texas, was the story “Woman Hollering Creek.”I didn't write it in 1984. I wrote it several years later, in 1987, when I didn't have any job in Austin. I was just teaching a writing workshop at the Women’s Peace House, and Liliana [Valenzuela, a poet and Sandra’s longtime translator] was in the class. I remember I was solicited to write a Texas story, and I took all the things that, since 1984, had been little pebbles in my shoe and gathered them up and I wrote Woman Hollering Creek. The stories there [are] about sitting in the icehouse with people who never spoke unless they were drunk - those were my colleagues from The Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center. The incident about the woman getting shot at that icehouse is in there. And a real incident of a woman who I gave a ride to – to the bus station – she’s at the center of the story. And my own story is in there, as well.

Woman Hollering Creek

and Other Stories

by Sandra Cisneros

Random House, 1991

El Arroyo de la Llorona y otros cuentos by Sandra Cisneros

Vintage Español, 1996

“Thich Nhat Hanh tells us that you have to go back to your spiritual roots…my spiritual roots were the Virgen de Guadalupe in Tepeyac. So I had to incorporate that into my Buddhism…”

Left: Tehuana dress by Isthmus of Tehuantepec, Oaxaca, worn by Sandra Cisneros to receive the National Medal of Arts from President Barack Obama at the White House, September 2016. Source: National Museum of Mexican Art (NMMA) Permanent Collection, 2017.13 A-B, Gift of Sandra Cisneros in honor of La Sra. María Luisa Camacho de López, “mi maestra”

Spiritual Path

Macarena: What I remember from meeting you (more than 20 years ago) was just how steeped in a spiritual path you were on and I don’t know if that had been a search for you or if that had been something you had been working towards before that. I know that in the case after my father’s death, my spiritual life came into a different focus. I wondered if the same had happened to you because you were instrumental in introducing me to Buddhism – Thich Nhat Hanh and Pema Chödrön—and other kinds of language for spirituality in my own life.

Sandra Cisneros, 2009

Sandra: It’s funny that you should ask that, because I just came back from the Miami Book Fair, and I talked a lot about nuns and priests, and I see them in a very different light than maybe people who have baggage. I just see everybody as being on a spiritual path–even if you’re not aware of it, you’re still on a spiritual path. I became aware that I was on some path when I got hit by a car at Iowa, when I was twenty-one, so I think that was a death and a rebirth for me. And then, my near-death when I went through deep depression when I was thirty-three and, subsequently, I felt as if I was searching for a spiritual practice. Being at Berkeley in 1988, I’d invited Jasna (my friend from Bosnia) to come and visit me, and she bought me a copy of Thich Nhat Hanh’s Being Peace from Old Wives Tales on Valencia Street in San Francisco. She gave it to me, and I said, “What’s this?” And she goes, “Oh! It looks interesting!” I didn’t read the book until the early nineties, when the Bosnian War started, and I was asked to give a speech in San Antonio for International Women’s Day March, and I felt very inarticulate about what I was going to say, so sometimes, I go to books for inspiration. I was looking on my shelf for something to inspire me, and this book fell off the shelf, and I thought, “Oh, here’s the book Jasna gave me.” I read that book, and it really was life-changing. I read it at the right time–it really did fall off the shelf for me to pay attention during the Bosnian War. I wrote the speech [“Who Wants Stories Now” (New York Times, 14 March 1993)] that is in my book of essays [A House of My Own: Stories from My Life (Knopf, 2015)], and I think that’s when Buddhism really took hold. I went to two retreats with Thich Nhat Hanh, and it really was life-changing for me. I found what I had been looking for, because Thich Nhat Hanh tells us that you have to go back to your spiritual roots. And to me, my spiritual roots were the Virgen de Guadalupe in Tepeyac. So I had to incorporate that into my Buddhism, and it seemed like I found a path by a man who was a poet, and Buddhist monk, and a war survivor, and an activist, and it all just fell into place for me. To find a camino that fit in with me being an artist and a witness, and activism that could come in my spirituality, I think right around then – early nineties. Then, by the time my father passed away in ‘97, I was already a Buddhist, and it influenced the way I looked at the novel Caramelo, because I wanted to write my father’s story, but in order to write his story, I had to explore, “How did my father learn how to love?” And in order to answer that question, I had to go look at his mother! And so it became, “How did I learn how to love?” It was like we were little Russian dolls, one inside the other. That’s how I wrote that book. It’s a real Buddhist book, actually. I don’t think of myself as being kind-of-like-a-Buddhist, like other Buddhists. This is funny to admit: there’s a Buddhist center across the street on my little alley, and I’ve never been there. [Laughs.] I keep meaning to. I’ve only been here [in San Miguel de Allende, Mexico] eight years, so maybe I’ll get in there one day; but I’m afraid that, if I go in, they’re going to make me do what the Catholic church did. You know, like, “Why weren't you here last Sunday?!” [Laughs.] And I don’t like getting up early on Sunday. That’s my alone time! Saturday and Sunday, I don’t want to see anybody, and I certainly don’t want to meditate in a room with other people.

Macarena: Wait, you got hit by a car? What happened that night in Iowa?

Sandra: I got hit by a car! And then I realized– I was walking – I have to write about this – and got hit while I was coming home from class, because I didn’t want to take the overpass. It was too dangerous to go into the woods [as a short-cut] to the student housing where I was living temporarily. So I went and crossed this – like, six-lane, four-lane, I don’t know – highway and, I guess, I was thinking of a poem in my head. I’d come back from a night class, and it was the beginning of the semester, and I got hit by this car and didn’t know what was happening until after it happened. I put a lot of the sound and the visuals in House on Mango Street, in the chapter “Red Clouds.” You know, where you see the sky slant, and you hear things, and you don’t know what’s going on. Well, that experience woke me up [to the fact] that I was not in control of my life, that there was this bigger thing, this horse that I was just caught in the stirrups of, that was dragging me across. And the idea that I was not in control of my life, but writing something that was already aimed somewhere, was quite fascinating. So, to me, that was the moment when I began, in earnest, a kind of mental journey. I was twenty-one and then, when I was thirty-three, I went through a year of near death and near suicide and, then again, that was a moment of spiritual awakening. I feel as if every ten years or so, I was getting closer to finding my camino, you know, my way. To me, my experiences living in Bosnia, and living with someone who was in a war-torn city, and finding Thich Nhat Hanh [were] so important in shaping me to become a Buddhist and to become an activist in a Buddhist way. If Thich Nhat Hanh can learn how to do that after the Vietnam War, I, too, having a friend and friends living in a city under siege, could find a way to make change in a nonviolent way. It truly was life-changing for me, and I think of all of those moments as kinda leading up to who I am. I don’t have it all figured out, but I know a lot more now than I did then.

Macarena: Would you say that Thich Nhat Hanh was one of your bigger or biggest spiritual teachers?

Sandra: I think Thich Nhat Hanh and Pema Chödrön. Those are the super-big ones of my life. Especially Thich Nhat Hanh, whose retreats I went to. So, yes. But I don’t have it all figured out, it’s not like I meditate every day. To me, writing is my meditation, and I find that, through writing, it takes me to places like the sitting meditation.

Macarena: So how would you describe your spirituality? What is it, Guadalupuddhista?

Sandra: I don’t know what I am. I don’t think I'm a very good Buddhist. I don't have a sangha [Buddhist community]. Oh, I don’t know. I just feel like I'm in some place where I know everybody has a spiritual path even if they don't know it, and I'm very happy when they do. If they resist and shut down because I talk about mine, there's nothing I can do about it. They're on their camino; I’m on mine. We’re in different dimensions.

Macarena: That’s interesting, because you’ve had a lot of Catholic influence, coming from a Mexican, Mexican-American home—because it’s so culturally Catholic. Even though your family was not very Catholic, you ended up in Catholic schools.

Sandra Cisneros as a Catholic-school student. Courtesy of Sandra Cisneros

Sandra: We weren’t in Catholic schools because we wanted to be raised Catholic. We were in Catholic schools because we wanted a good education. It had nothing to do with my father’s spiritual beliefs and my mother’s. We were in neighborhoods where things were rough and tough and chaotic and overcrowded in the Chicago public schools. We didn't have a choice. If [a private school] had been Quaker, we would have gone there. If it had been a Methodist school, we would have gone there. It was just what was available. If it had been Buddhist, we would have gone there. My mother and my father were alerted to how chaotic the public schools were by my brother, who [had come] back from Mexico and was super disciplined in military school. I didn't know any better, because I had only been to public schools, and I didn’t know that it was chaotic [until] my brother came home and complained and insisted that we had to be taken out of that school and enrolled somewhere else. It was my oldest brother! You see what a czar he was? He demanded that we be taken out of public school and put into Catholic school. We went to Catholic school, and I didn’t know my prayers. I remember that they began class with prayers; I didn’t know my prayers. I didn't know the sign of the cross. I didn’t know anything! I remember everybody went, you know, did this [demonstrates], and I went [demonstrates]. I didn’t know what to do! Plus, we had to go to Mass, and it was in Latin. We had to get up and kneel. I never went to Mass. Suddenly, in the second grade, I was behind in catechism. Supposedly, I didn’t have my Holy Communion? I didn’t have Holy Communion, but I had all the other sacraments they give you when you’re a baby in Mexico. They confirm you, they baptize you, everything except the last rites and Communion. I was woefully behind, and I had to learn all of the catechisms [in order] to prepare for Communion overnight. The only thing my family believed in was going to Maxwell Street, the flea market, on Sunday. We didn’t go to church.

Macarena: Am I imagining this? That you were a Sunday-school teacher?

Sandra: I was, but that was by accident. I was a very dutiful student in middle school, and the nuns liked me, and they asked if I wanted to volunteer to be a CCD [Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, also commonly known as Catechism] teacher. I said, “Oh, Sister! I cannot at night. My father won’t let me go!” “We’ll pick you up in the car.” I said, “Oh! I don’t think my father would object to sisters picking me up.” So in seventh grade and eighth, I was a CCD teacher. They must have had a real shortage if they were scraping the bottom of the barrel to recruit me. But I guess I fooled everyone into thinking I was very devout. I taught first grade and, at first, I had a real hard time because I couldn't keep their attention. Then later on, I realized, because I could draw, I would take big drawings, like hyper, big-sized paper my father brought home from work, and I would draw scenes from whatever lesson it was—The Good Shepherd or whatever the Bible story. Then, if you behaved, I would give you the drawing. So there was like a giveaway of these huge drawings. You had to roll them up; they were the size of a kitchen table. They were big drawings so [that] the class could see them, and these students really behaved if they wanted those drawings that I made. And that’s how I controlled my class—through pictures, telling the story through pictures.