Calavera Images and José Guadalupe Posada

Jim Nikas digs up how the 19th-century Mexican graphic artist popularized the skull imagery associated with Día de Los Muertos [Day of the Dead]

[Gran calavera eléctrica] by José Guadalupe Posada depicts a large skeleton hypnotizing a sitting skeleton and a group of skulls; shown in the background is an electric trolley filled with skeleton passengers. Source: Library of Congress [LC-DIG-ppmsc-04468]

The Posada Art Foundation was founded by educator, producer, and screenwriter Jim Nikas with the mission to educate, inspire, and sustain the legacy of Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada (1852-1913). The Foundation supports a variety of not-for-profit organizations projects in the visual arts and education that assist youth development, as well as organizations involved in education and research in social movements. José Guadalupe Posada Legendary Printmaker of Mexico—a traveling exhibition organized by The Catalina Island Museum in Avalon, California in association with The Posada Art Foundation—is currently on view in Escondido, California, then headed to Glen Falls, New York and Las Cruces, New Mexico through 2023.

Below is a shortened version of an essay written for a past exhibition and published on the Foundation website as “Day of the Dead (Día de Muertos) Calavera Images and José Guadalupe Posada.” Note: The word “calavera,” as used here, refers to the term “skeleton” or “skull.” In Mexico, the word can have many meanings and uses. The word “calaca” is generally used in reference to the skeleton, but for simplicity, only “calavera” is used here.

Between 1882 and 1913, Mexican graphic artists José Guadalupe Posada and Manuel Manilla created dozens of calavera (skeleton) images while employed by the Mexico City-based printing house of Antonio Vanegas Arroyo.

The images appeared in a variety of publications called broadsides, also known as hojas volantes (literally “flying leaves”). Usually one to two pages in length, the broadsides were an inexpensive form of publication containing a variety of news, commentaries, and entertainment popular at the time. During October and November, Vanegas Arroyo issued broadsides containing images of calaveras to coincide with the early November observance of Day of the Dead. While the calavera imagery was not the invention of Vanegas Arroyo, Manilla or Posada, there can be little doubt that they lay the foundation for its popularization in the current century.

Broadside published by Antonio Vanegas Arroyo, with illustrations by José Guadalupe Posada (top) and Manuel Manilla.

Note active vs. passive images: Posada’s depicts a calavera of Don Quixote riding an equally skeletal horse, charging other skeletons with his lance; Manilla’s shows calaveras outside a cemetery pursuing a group of young men and women.

“Esta es de Don Quijote la primera, la sin par, la gigante calavera [This one is of Don Quixote the first , the unparalleled, the giant skull],” ca. 1910-1913.

Source: Library of Congress [LC-DIG-ppmsc-04597]

Early Mesoamerican uses of the calavera

Paleoanthropologists have studied the uses of calaveras for many years. The literature, in terms of academic research papers and books, on the subject is extensive (several publications are referenced below for further reading). Skeletal images were used in pre-Columbian times by peoples living throughout wide areas in Mexico and portions of Central America. Some of the best known calavera images have been found in numerous Aztec and Mayan archeological sites, including, but not limited to: Teotihuacán, Templo Mayor in Mexico City; Chichen Itza along Mexico’s Gulf Coast; Tikal in Northern Guatemala; and Copán in Honduras. Development of what might be called the first cities with temples containing calavera imagery may be assigned at present to the Middle Pre-classic Period of about 1,000 to 300 BCE (Before Current Era). Examples of the oldest known calavera statuary in the region belong to the Olmec people, who lived approximately 1,200 to 400 BCE.

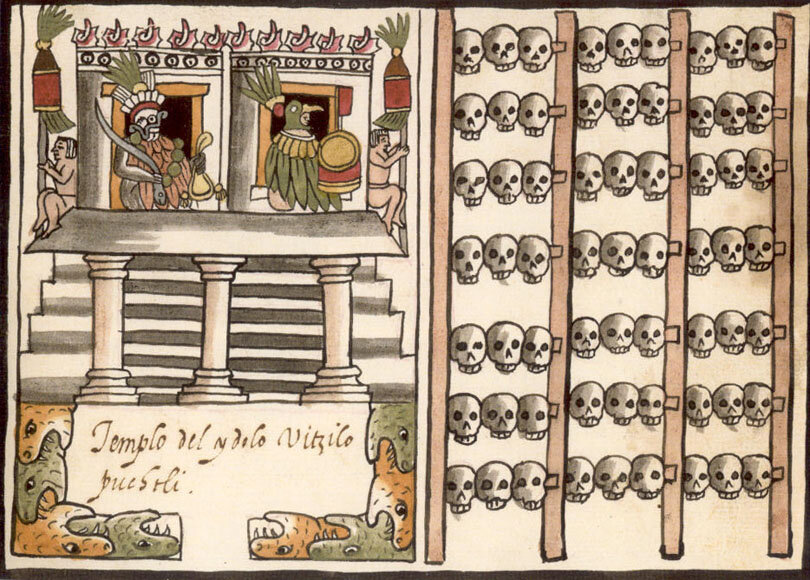

The main observations made of Mesoamerican uses and symbolic meanings of calavera imagery include:

Actual skulls resulting from human sacrifice, the belief being that human sacrifice fed the gods, which in turn would ensure continuity by allowing the Sun to rise and life to continue;

As sculpted symbols, calaveras might have served as markers or sign posts demonstrating respect to the gods while also signifying places of ritual or of a sacred nature, and the calaveras may be symbolic reminders of Death’s constant presence and of the duality of life in that there can be no life without death;

The skull racks of Mexico or tzompantlis likely served to remind the population of the day that obligations to the gods must be met and as a symbol of power—the more skulls exhibited, the more powerful were the people who put them there presumed to be.

Background of Día de los Muertos

Customs and traditions of people evolve and change over time. This is especially true when one culture is invaded and conquered or dominated by another. Where the Mesoamerican cultures are concerned, Spanish invasion and conquest resulted in a blending of cultural traditions, combining elements from the Catholic Church (i.e., the centuries-old Judeo-Christian veneration of the dead on All Souls’ Day) with Mesoamerican beliefs. The Spanish crown and Catholic Church, as the conquerors of Mexico, had the dominant influence. There is no exact date when the cultures began to merge, but a general beginning might be assigned to the year 1521 AD, coinciding with the general date of what is referred to as the “Conquest of Mexico.” However, not all regions of Mexico were brought under Spanish rule that year, and certainly the dismantling of native Mesoamerican cultures did not happen overnight. The changes evolved over many years. It might also be argued that the traditions of native Mesoamerican cultures were not dismantled but that they evolved and continue to evolve.

The years following 1521 AD reveal both common and clear differences between European and Mesoamerican cultural elements. Both observed death with a view that took into account ancestors and an honoring of deceased souls. Both cultures considered the journey of souls in the afterlife, and both designated times of observance during the calendar year.

Mesoamerican cultures observed the time over a longer period and at a different time of the year. To this author, these temporal differences in observance provided the foundation for the Spanish-Catholic Church to exert dominance, resulting in the gradual melding and adoption of the Day of the Dead period, between October 31 and November 2. Certainly, there were also significant differences in belief systems (for example, Mesoamerican cultures were polytheistic vs. the monotheistic Judeo-Christian system), but again, the similarities allowed for a gradual blending of both cultures’ approaches to observing the dead.

One other related similarity worth consideration is the concept of what might be called “spiritual layers.” Both Mesoamerican and European belief systems had main divisions and sub-layers occupied by souls, with God or Gods, angels, and saints dwelling within them in one way or another.

At the time of the conquest, the Aztec belief system included three main parts: 1) the earth world inhabited by the living; 2) an underworld called Mictlān, inhabited by the dead and ruled over by Mictlanteculhtli, god of the underworld, with his goddess wife Mictecacihuatl; and 3) the upper plane in the sky, where only deities dwelt. Between the earth and netherworld were layers where souls, deities, and mythical beings might travel.

By contrast, the Catholic Church had three main divisions or layers: Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory. Earth, although not perhaps an official level, might be considered a fourth layer, inhabited by the living. Purgatory, beginning in the 14th century helped create a multitude of levels—and thanks to the popularity of The Inferno, a literary work by Italian poet Dante Alighieri (1265-1321)—including Limbo, which was recognized by the Catholic Church (until a ruling in 2007 by Pope Benedict XVI eliminated it) and remained a part of the Church’s system of belief for over 800 years.

As the Catholic Church began to evangelize the population of Mexico, there was clear advantage in accommodating the existing observances of All Souls’ Day, All Saints’ Day, and Day of the Dead. Giving respect and honor to ancestors were unifying elements—everyone has ancestors and family, we all come from somewhere, and all of us perish. There is also the universal question, What happens to us after we die? These common elements likely helped in the adaptation and evolution of the Day of the Dead observance. Elements of these systems drive and are of influence even today. To some extent, they are likely partially responsible for the growing popularity of the Day of the Dead and, ultimately, of Posada’s calavera images.

Mictlanteculhtli, god of the underworld, dwells in Mictlān with his goddess wife Mictecacihuatl. Museo del Templo Mayor, Mexico City, Mexico.

Photo: Travis Shinabarger

José Guadalupe Posada, Manuel Manilla, and Antonio Vanegas Arroyo

As Posada’s main publisher, Vanegas Arroyo played a significant role in developing the popularity of calavera imagery as related to the Day of the Dead in Mexico. Posada’s predecessor at the printing house was Manilla, who joined sometime around 1882 and left, it is believed, around 1892. Given that he had been at the printing house approximately seven years before Posada, it might be said that Manilla’s images of calaveras tested the waters for how the images would be received in the market. Later, when Posada joined the artistic team, his more frenetic and dynamic style brought the calaveras to life, as illustrated in the broadside “Esta es de Don Quijote la primera, la sin par, la gigante calavera” (see above). Manilla, however, appears to be the first illustrator charged with producing the earliest calavera images for the Vanegas Arroyo publishing house, although Posada generally gets the credit for their popularization. Where or how Vanegas Arroyo acquired the idea of using calaveras in his publications is difficult to establish.

Three elements may have contributed to the inspiration.

The first, to some extent, might be traced back to imagery in the book La portentosa vida de la muerte [The Ominous Life of Death], written in 1792 by Franciscan priest Joaquín Bolaños. The first treatise on death ever written in Mexico, the book contains 18 skeletal depictions by Mexican engraver Francisco Agüera Bustamante. Like Posada, Bustamante was a talented artist who contributed illustrations to a variety of 18th-century books, but the calavera images contained in Bolaños’s book are unique in that, as media writer Regina M. Marchi suggests, Bustamante himself may have drawn inspiration from European prints depicting the “Dance of Death”.

Where exactly Bustamante and Bolaños acquired their own inspiration to utilize calavera images, however, is unknown— but Marchi’s speculation that they were influenced by art works of European origin certainly seems possible.

Dating back as early as the 15th century, European skeletal depictions appeared in murals and later in paintings. These images have been grouped by numerous authors into an allegorical category called the Danse Macabre (French for “Dance of Death”) and also into a related class of skeletal living-death imagery referenced in Latin as memento mori. Ultimately, both references remind us to reflect on death, that all living things die.

Engraving by FG Bustamante in Joaquín Bolaños’s 1792 La portentosa vida de la muerte [The Ominous Life of Death]. Image source: Swann Auction Galleries

Detail of a Dance Macabre fresco (1490) by Johannes de Castua in the Holy Trinity Church in Hrastovlje, Slovenia. Photo: Bibliofil at cs.wikipedia, CC BY-SA 3.0

In a book actually entitled Danse Macabre, German painter and printmaker Hans Holbein the Younger (1497–1543), used the imagery when reflecting on European skeletal designs. The images were drawn by Hans Lützelburger and published in Lyon, France in 1538. Apparently, the images in Danse Macabre were very popular. It could be argued that this popularity—like the images by Posada and Manilla—led to their widespread copying and distribution over the years following 1538, as the images have appeared in many forms throughout Europe.

Could some of these or similar images have found their way into the hands of publishers and artists in Mexico? It is certainly possible, as literature was definitely exchanged between the Old and New Worlds. There are, for example, a variety of chapbooks published by Vanegas Arroyo that have their roots in the fables and tales of European literature. Looking at the stories contained in the Blue Fairy Book (published in 1889), a collection of fairy stories compiled by Andrew Lang (1844-1912), one sees story titles such as “Blue Beard” and “Puss in Boots,” among others, all adapted by Vanegas Arroyo, with illustrations by Manilla and Posada.

“Abdis en de Dood [The Abbess],” Plate 15 in Danse Macabre by Hans Lützelburger, published in Lyon, France in 1538. Source: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

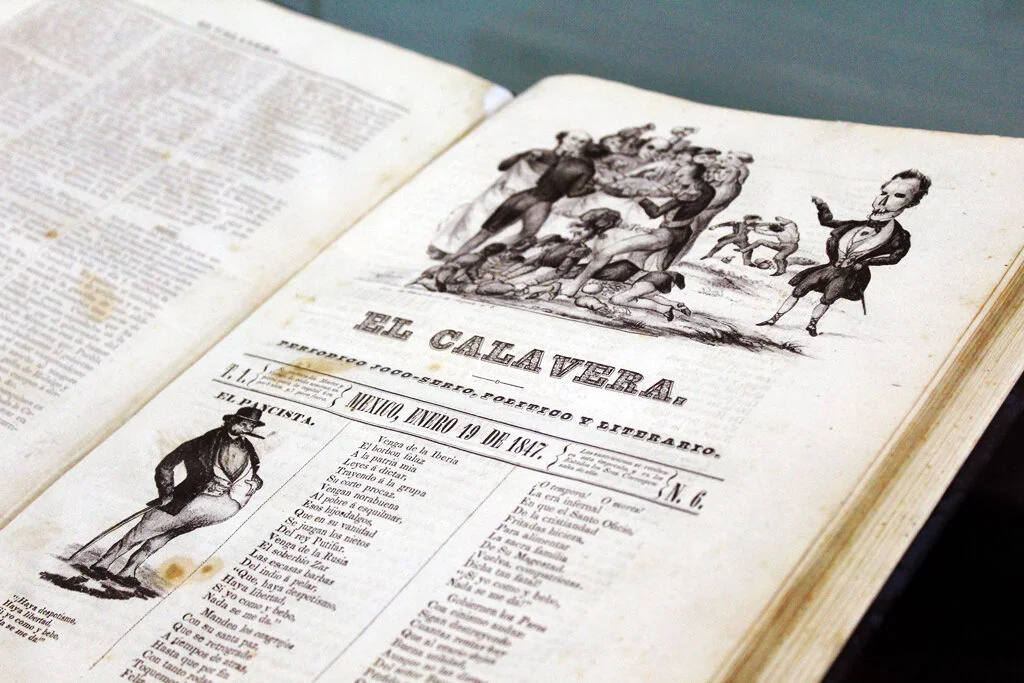

In 1847, a short-lived weekly publication called El Calavera appeared in Mexico. The first illustrated newspaper in the country, this publication symbolically used anonymously drawn images of calaveras to help communicate social, political, and satirical commentary. Although Vanegas Arroyo did not start his publishing business until 1880, it is reasonable to speculate that he may have also drawn inspiration or gained the general idea of using calaveras for social commentary from the El Calavera.

The Belgian artist James Ensor (1860-1949) also used skeletal images in satirical illustrations. During his lifetime, he produced 133 etchings and drypoints, of which 86 were made between 1886 and 1891. Might some of the images have made it to the eyes of Vanegas Arroyo?

El Calavera, edited during the first half of 1847, made political use of calaveras to illustrate the “internal and external war that bled and mutilated Mexico” (Archivo General de la Nación). Source: Gobierno de México

In addition to the 19th-century records of prints noted so far, there are other examples of calavera representations in Mexico during the latter portion of the 19th and early 20th centuries, prior to what might be called the first radiation of their use (mainly from Manilla and Posada).

The first known use of a calavera by Posada was not for Vanegas Arroyo but for Ireneo Paz’s publication La Patria Illustrada in 1889. We know that calavera images had been used by many other publications that were active during Manilla’s and Posada’s time, including El Hijo del Ahuizote, El Buen Tono, and El Cómico. We also know, thanks to the research of historian Helia Emma Bonilla Reyna, that Posada made images to order, as described in the documentation of a lawsuit in which Posada sued an editor for non-payment. It can be said with certainty that the calavera imagery signed by and attributed to him has been reproduced and repurposed for over one-hundred years, out-living his many editors. Whatever notoriety Posada the artist enjoys today is over-shadowed by the popularity of his beloved calaveras (note that Posada also illustrated books and many other images political and non-political), and yet the visibility of his name and imagery is due mainly to Posada’s discovery and promotion in the 1920s and 1930s by artist Jean Charlot and acknowledgements from artists such as famed muralist Diego Rivera. Publications by Frances Toor (in “Mexican Folkways” and in the POSADA: Monografía) and Anita Brenner (in Idols Behind Altars) were instrumental in promoting Posada’s imagery. But with little doubt, the widespread use of the calavera for political images created by the famed Mexican artist cooperative Taller Gráfica Popular in the 1930s and 1940s is very much responsible for helping to promote the utility of the calavera as a political vehicle.

Again, while neither Manilla, Posada nor Vanegas Arroyo invented popular representations of the calavera, how it evolved as an icon at the time is an interesting study.

Front cover of La Patria ilustrada (4 Nov 1889), México—some speculate it is among Posada’s first calavera illustrations. Source: Biblioteca Nacional de México (Instituto de Investigaciones Bibliográficas, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México [UNAM]), Biblioteca y Hemeroteca Nacional Digital de México

The Popular Calavera

The calavera is something we all have biologically in common and, accordingly, may be used to convey messages. Even after more than one-hundred years since Posada's death, the most reproduced and influential images of calaveras are those that he created. Posada and his publishers used depictions of calaveras not only to remind us of our collective mortality but also to shed light. His illustrations were often satirical caricatures uprooted from the current political climate and used to poke fun at our human condition. This use was evolutionary, occurring over time, and as applicable today as it was over a century ago.

Images of death—borrowed from the ancient traditions of the indigenous Mexicas and juxtaposed with the living though Posada's "cartoons"—present the inevitability of cultures and traditions colliding: a Western European Spanish Christian cultural view of death vis-à-vis the Conquest versus the Mexicas’ polydeistic belief system of rebirth. Somewhat simplistically, it could be said that the Mexicas provided the Spanish with the opportunity to get in touch with their "inner calaveras." So, too, for all of us living in the modern day.

¡Viva Posada!

Day of the Dead mini-exhibition installed by the Posada Art Foundation at the Consulate General of Mexico in San Francisco, California, on view from October through November 2021.

General References

Bonilla, Helia, ed., and José Posada, Rafael Barajas, Mercurio López Casillas, Monserrat Galí, and Juan Villoro. 2014. Posada: A Century of Skeletons, Mexico City, Mexico, RM Publishers.

Brandes, Stanley. 1997. “Sugar, Colonialism, and Death: On the Origins of Mexico's Day of the Dead.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 39: 270-299.

Brenner, Anita. 1929. Idols Behind Altars. Payson and Clarke, Ltd. New York.

Carmichael, Elizabeth, and Chloe Sayer. 1991. The Skeleton at the Feast: The Day of the Dead in Mexico. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Coe, Michael D., and Rex Koontz. 2008. Mexico: From the Olmecs to the Aztecs, 6th Edition. New York: Thames and Hudson.

Diehl, Richard A. 2004. The Olmecs: America's First Civilization. London: Thames and Hudson.

Fernández Kelly, Patricia. 1974. “Death in Mexican Folk Culture.” American Quarterly 25: 516-35.

Foster, George M. 1960. “Culture and Conquest: America's Spanish Heritage.” Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, No. 27. New York: Wenner-Gren Foundation.

Fuente, Beatríz de la. 1974. Arte prehispánico funerario: EI occidente de México. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Gabriel Llompart, C. R. 1965. “Pan sobre la tumba.” Revista de dialectología y tradiciones populares (Madrid) II: 96-102.

Gibson, Charles. 1964. The Aztecs under Spanish Rule: A History of the Indians of the Valley of Mexico, 1519-1810. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Ivins, Jr., William M. 1919. "Hans Holbein's Dance of Death." The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 14, no. 11 (November): 231–235.

Marchi, Regina M. 2009. Day of the Dead in the USA: The Migration and Transformation of a Cultural Phenomenon. Rutgers University Press.

Toor, Frances, Blas Vanegas Arroyo, and Pablo O’Higgins. 1930. POSADA Monografía de 406 grabados de José Guadalupe Posada. Frances Toor/Mexican Folkways.

Tyler, Ron, ed. 1979. Posada’s Mexico. Library of Congress.

Van Gindertael, Rodger. 1975. Ensor. Boston: New York Graphic Society Limited.

Westheim, Paul. 1983. La calavera. 3d ed. Mexico: Fondo de cultura económica.

Whyte, Florence. 1931. The Dance of Death in Spain and Catalonia. Baltimore, MD: Waverly.

Winning, Hugo von, and Louise Noelle, ed. 1987. “EI simbolismo del arte funerario de Teotihuacán.” Arte funerario Vol. I: 55-63. Mexico: Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México.

Wollen, Peter. 1989. “Introduction.” Posada: Messenger of Mortality. Redstone Press.

![[Gran calavera eléctrica] by José Guadalupe Posada depicts a large skeleton hypnotizing a sitting skeleton and a group of skulls; shown in the background is an electric trolley filled with skeleton passengers. Source: Library of Congress [LC-DIG-ppmsc-04468]](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5da9ca4316ddf940acff02af/1633879121358-AFZ6BH21EU0AAJY5U8ZY/Gran-calavera-electrica-Posada.jpeg)

![Engraving by FG Bustamante in Joaquín Bolaños’s 1792 La portentosa vida de la muerte [The Ominous Life of Death]. Image source: Swann Auction Galleries](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5da9ca4316ddf940acff02af/1634387395726-YE8Q8UVHZK70RJB7LHI5/Portentosa-vida-de-la-muerte.jpeg)

![“Abdis en de Dood [The Abbess],” Plate 15 in Danse Macabre by Hans Lützelburger, published in Lyon, France in 1538. Source: Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5da9ca4316ddf940acff02af/1634386546225-OR45AARDTE1GEPFJ8MI3/The+Abbess.jpeg)