St. Everyday (Part II): Mais Viva!

Dr. Xochitl Alvizo and students ‘heart’ Gabriel García Román’s visit to their Queer Theory class

Dr. Xochitl Alvizo and students ‘heart’ Gabriel García Román’s visit to their Queer Theory class

When I was first introduced to the work of Gabriel García Román’s work, specifically the Queer Icons portrait series, I noted the immediate connection between his art and the subjects I teach in my Queer Studies and Religious Studies classrooms at California State University, Northridge.

The intersection of religious studies/theology and queer theory is always a little surprising to my students. For them, issues of gender, sex, and sexuality are very fixed ideas in relation to religion, and they do not expect much new information on the topic – much less positive or constructive perspectives. As I see it, though, part of my job in the classroom is precisely to complexify and bring out the many dimensions inherent to the subject and to move students from their assumed, inherited, and usually uncritical perspectives to a more nuanced and complex understanding of religion and sex, gender, and sexuality. I therefore have my students engage work that scholars, religious leaders, and activists are producing in these areas, often born out of social-justice commitments.

Left to right: Rev. Freda (n.d.) and Fei Hernandez (2018). From the Queer Icons series by Gabriel García Román.

The impact of Gabriel’s Queer Icons on my students’ imagination is very often paradigm-shifting and liberative, especially as they become equipped with new theorical lenses from which to continue viewing and engaging with this subject and in light of the usual (negative and judgmental) messages and news reports they encounter in the media about religion and LGBTQ lives. As some students observed:

I definitely have this sense of urgency to live, to resist death not only out on the streets but sometimes within the home…It's inspiring to see stories like Fei Hernandez and Jay Ulanday Barrett, seeing people like me continue to live on today. But how much longer do we have to resist death? (del Rosario)

I learned that the word activist is more than just a word. Activists have faces, are educated, scholars, artists, creators, courageous, speakers, writers, strong as a result of personal experiences that have shaped them...I see Gabriel's work differently now. I see it as a tribute to activists who don't stop, don't hide, and fight a daily battle for the rest of us. (Thompson)

Gabriel introduces the Queer Icons series to the class

(includes a few brave students who were willing to appear on camera)

In my classes, whenever I use art or visual media to spark the discussion, we start with two questions, distinctly engaging with each, one at a time: What do you see? What do you wonder?

I emphasize to the students that they should first only make strict observations, withholding their evaluation, interpretation, or judgment for later, and only name what is observable. Once they’ve done that, they can then raise questions about the art–but only questions that are directly related to what they first observed. This allows students to open themselves up to new insight and to keep from simply jump to their brains’ already embedded associations, interpretations, or judgments—an important task indeed when one is reflecting on the intersection of religion and sex/gender/sexuality.

On the day of Gabriel’s visit to our class, the students followed this two-question process with two of his Queer Icons and shared their impressions of his art right in his presence. They did a wonderful job and asked him many detailed questions about his process, material, colors, and, especially, his inspiration.

In turn, Gabriel engages with the portrait work of interdisciplinary scholar, artist, and activist Dr. Dora Silva Santana.

Gabriel responds to students of Queer Theory

Dr. Dora Silva Santana, a Black trans feminist scholar from Brazil, is a faculty member at John Jay College, CUNY. She believes that “academia can be a strategic space for critical thinking leading to social transformation.”

I first encountered Santana’s work when researching trans queer of color scholars for my Perspectives in Queer Studies class. And while Santana’s work does not explicitly engage religion, her theoretical lens helps to interrogate religion’s death-dealing approaches to queer living. I specifically use her article “Mais Viva!: Reassembling Transness, Blackness, and Feminism” (Transgender Studies Quarterly, 1 May 2019) to provide a framework with which students can interrogate the negative and death-centered lens through which Queer lives are most often presented in media, art, and, of course, within religious communities. Santana puts forth the concept of “mais viva,” a Brazilian Portuguese term meaning “more alive, alert, savvy.” Santana introduces the expression to capture the “embodied knowledge of black and trans resistance, [as] a kind of critical awareness necessary for building self-love and building community.” Mais viva is a way of living that targeted communities find necessary in the face of ongoing harassment and marginalization.

Herself a trans woman, Santana asks:

“What are the strategies of resistance and care for ourselves and our communities in the face of the haunting and material presence of death? How do we imagine possibilities of livable lives, of freedom, well-being, and transformative change, as we resist death?” (210-11)

Dora, portrait of Dora Silva Santana by Drew Riley. From Gender Portraits, a nonprofit project of the Austin Creative Alliance that advocates for sex and gender minorities through art.

Conducting research with travesti women and activists, and collaborating with black feminists in Brazil, Santana comes to identify the “Afro-diasporic legacy of fugitivity” that is embodied in a community’s “refusal to lose oneself” (210). This fugitivity and refusal to lose oneself, to be mais viva, amid the reality of diaspora, of being in movement and transformation, “make[s] intelligible the embodied...call for action of black and trans people transnationally” (210).

For the purposes of my class, the importance of Santana’s scholarship and Gabriel’s art lies in how their work brings attention to the strategies of resistance that are about queer living, not their dying, a vitality seldom given attention to in the media. As both Gabriel and Santana observe, what dominates in the news about members of the LGBTQ+ community is related to their death or murder – an individual typically being spoken about only as corpse.

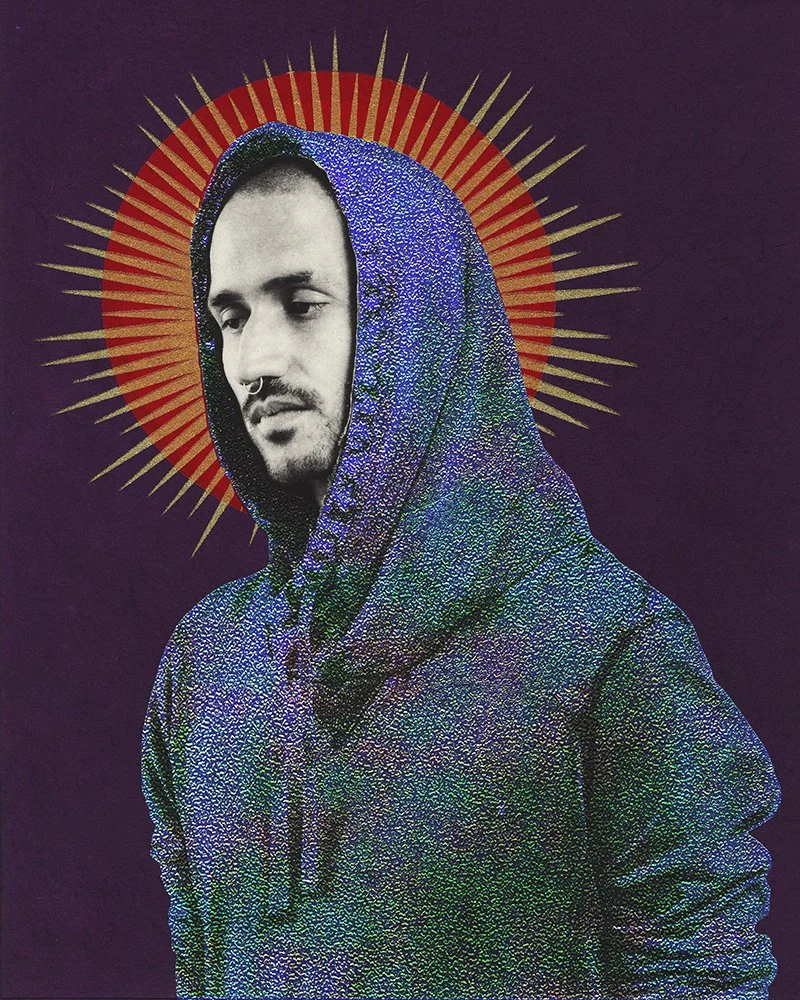

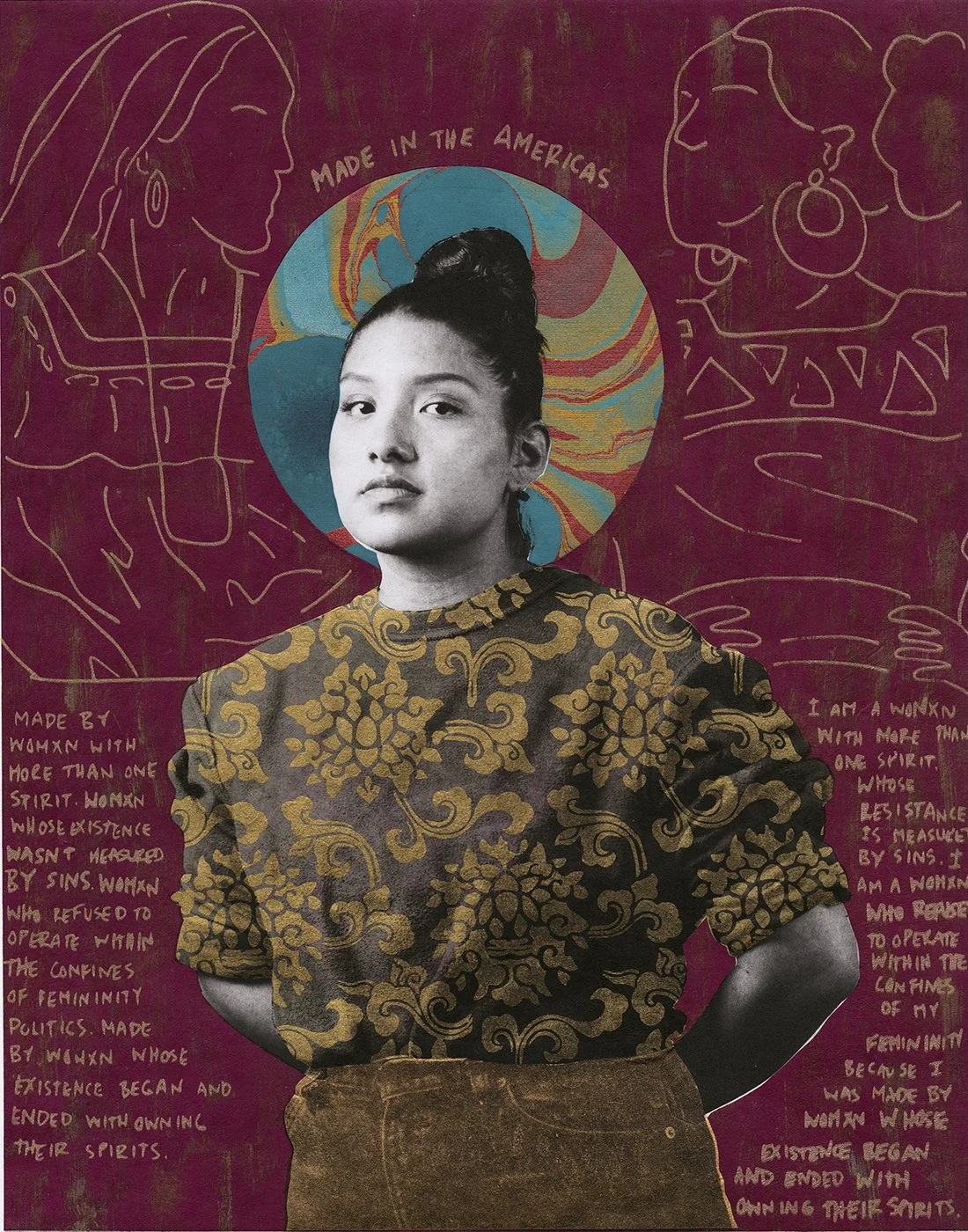

Like Santana’s methodology aims to do, Gabriel’s Queer Icons portrait series humanizes the LGBTQ+ community, presenting a collective of individual lives, people he holds up as saints and icons because of their living and of the ways they advocate for and advance their communities. Queer Icons celebrates and sanctifies queer living and their social-justice legacies. Each Queer Icon is a representation of a person mais viva – of their strength and power, their activism, and their refusal to lose themselves. And their vivir is extended through the work they do for their communities.

Gabriel reflects on the intersection of Santana’s work with his own

In the spring of 2021, feeling the need for a change of scenery, Gabriel visited his native state of Zacatecas, Mexico. Even this choice to take a trip, with the aim to “rebuild and re-emerge whole,” Gabriel captures well the spirit that likewise goes into his work – his commitment to fill in a gap he saw in the art work and actively counter-narrate the way queer lives are often negatively reflected. During my interview with Gabriel, I am also struck by how grounded in purpose he is and how integrated his values are in various aspects of his life.

“This is my life's work,” he says. Sometimes I like to visualize myself as a monk in the mountains, just working on something, and this is going to be what I do for the rest of my life, and I will be completely content just doing that.”

I think about academics and the place within us from which our own work flows. For us, too, there is a beauty that comes through when our work emerges from a grounded place: our own values and commitments.

As one student, Duran, puts it: “What shines through the most for me is the pride. [Queer Icons] is a beautiful stance of disruption. It’s an exclamation that I am beautiful here and now.”

The world needs more of this beauty.

Highlights from Student Reflections

del Rosario: I definitely have this sense of urgency to live, to resist death not only out on the streets but sometimes within the home. It's inspiring to see stories like Fei Hernandez and Jay Ulanday Barrett, seeing people like me continue to live on today. But how much longer do we have to resist death?

Cantu: All of the people in Gabriel’s art imagine possibilities…and their existence is resistance. The subjects are resisting by existing, every single one of them, they are either decolonizing or being anti-colonial, and that is the cure.

Villareal: [Regarding the religious motif] I almost immediately noticed the halo-like effect behind everyone's head. I could tell that the artist purposely wanted to show them in a saint-like position because religion is a very important aspect on many people of color's life.

Ueng: I see each and one of their pride to confidently stand in front of a camera being bold and proud of who they are. There is this sense of fierceness that you can see in each person's eyes, the unapologetic look, the look that says "I am not sorry, I am doing this on purpose and living." The reason why portraits are amazing is because we can see a finer detail of a person's face and figure.

Thompson: Initially, I saw Gabriel Garcia Roman's work as an homage to the many queer and trans people who are living their lives openly, at some risk to their safety and the comfort of societal norms. I saw these people as gender-fluid, queer, and unafraid bold warriors leading the cause for queer rights and greater freedoms. I loved the photography and their short but inspiring biographies. After going through Roman's website I spent time digesting the readings…I learned that the word activist is more than just a word. Activists have faces, are educated, scholars, artists, creators, courageous, speakers, writers, strong as a result of personal experiences that have shaped them.

My final read of [Santana’s] first paragraph was much clearer. It was about an experience of seeking out kinship, community, "livable lives," safety, more "freedom" and stability in a hostile cis-heteronormative environment where Trans people are tolerated at best, but constantly on high alert and having to live on their nerves and instincts to survive. I see Gabriel's work differently now. I see it as a tribute to activists who don't stop, don't hide, and fight a daily battle for the rest of us.

His work has inspired me to do more, to push harder and to seja mais viva!

Duran: What shines through the most for me is the pride. This collection is a beautiful stance of disruption. It’s an exclamation that I am beautiful here and now; by my standard of beauty and embrace for every shape, face, color, background, sexuality and experiences we all have as individuals. As Dora Santana stated we need to seek understanding of each other's unique life experiences, so we can truly discuss allegiance with each and truly advocate for genuine change.

Martin: Once I took this reality in [Santana’s method from the article], I could so clearly see the strength in the eyes of each of Gabriel's subjects. I found myself even more interested in their lives and their stories than I ever was before. Each of the people illustrated have their own story like Selen's and they deserve to be heard. Being able to revisit Gabriel's work really just gave me a much deeper appreciation for all that he was doing.

Cho: I really enjoyed the reading in connection to the photos…I can feel the energy of the people standing in the photos considering I might have had similar experiences of societal judgment. I also liked how the paintings gave off a saint-inspired aesthetic around these queers to give them a look of a healing higher power…I was mesmerized with the way they were all illustrated. At first, they appeared like saints, but after careful inspection, they were not depictions of traditional saints, but definitely on the spectrum of divine creatures…These illustrations alone demanded my attention for minutes at a time.

Gonzalez: After reading, Mais Viva! by Dora Silva Santana and focusing on the A luta é nossa! Viva a vida! (It Is Our Fight! Live Life!): Fugitivity as Refusal section, I felt it was really powerful for this passage to demonstrate despite being discriminated against and constantly met with challenges of violence or hate, you still must move forward…This theme of “live life!” embodies motifs of will-power, courage, and resilience. There is something not just incredibly beautiful about that, but also alluring in the sense of wanting that exact same attitude and mindset for life. After revisiting Gabriel Garcia Roman’s works, I got that same sense of rebellion, anarchy, and war for spiritual freedom from each [icon]…In the revisit, each individual’s beauty and humanity stood out to me more. Each life has a beautiful story to tell, and as I continue to look through each person’s story, I feel even more grateful that they shared such an emotionally-moving artistic profile of themselves. Additionally, I began to appreciate the hints of religious style in the art depictions even more.

Embroidered corazón patch by Gabriel García Román

View Gabriel García Román’s work at http://www.gabrielgarciaroman.com/.

St. Everyday (Part I): Queer Icons

Dr. Xochitl Alvizo profiles artist Gabriel García Román, creator of the QTPOC portrait series

Dr. Xochitl Alvizo profiles artist Gabriel García Román, creator of the QTPOC portrait series

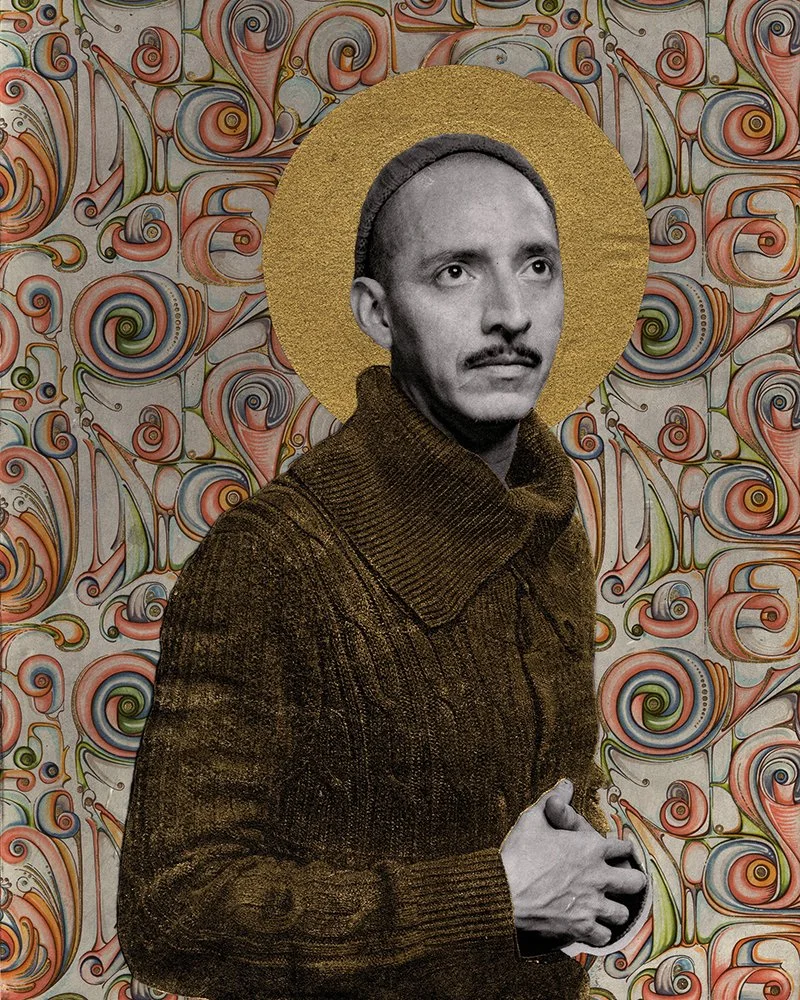

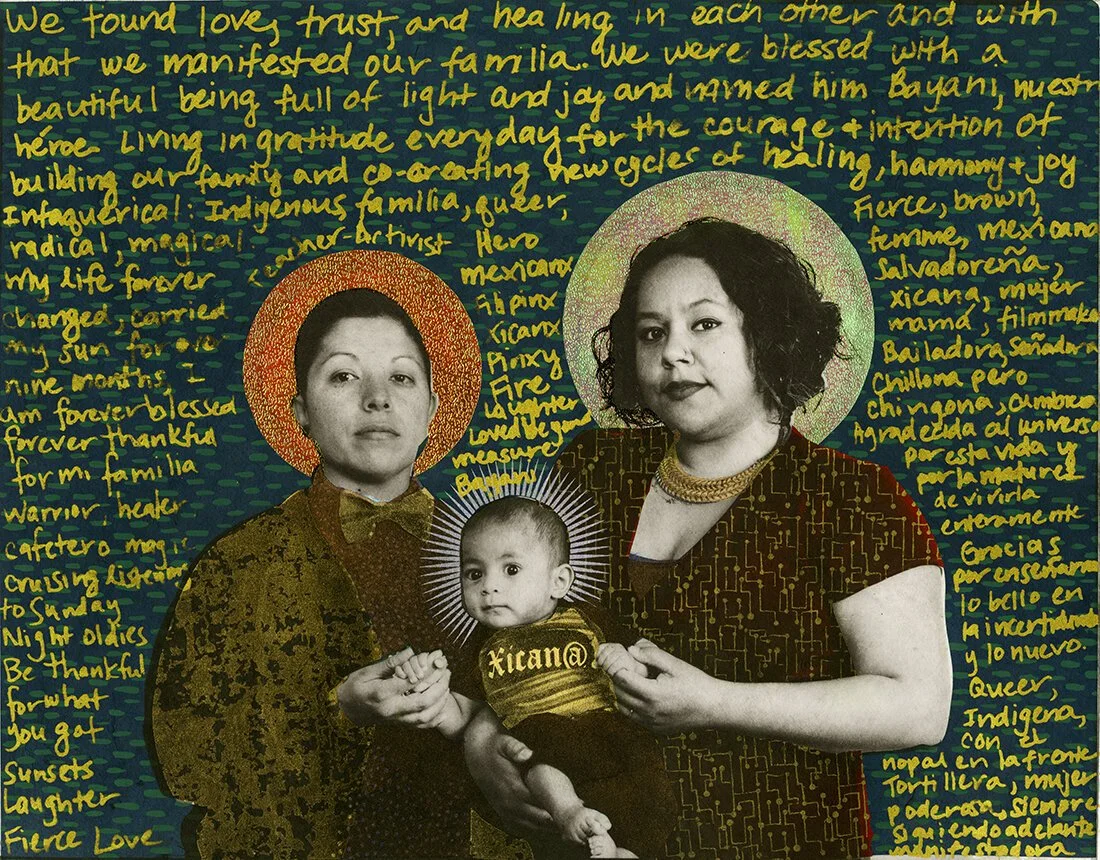

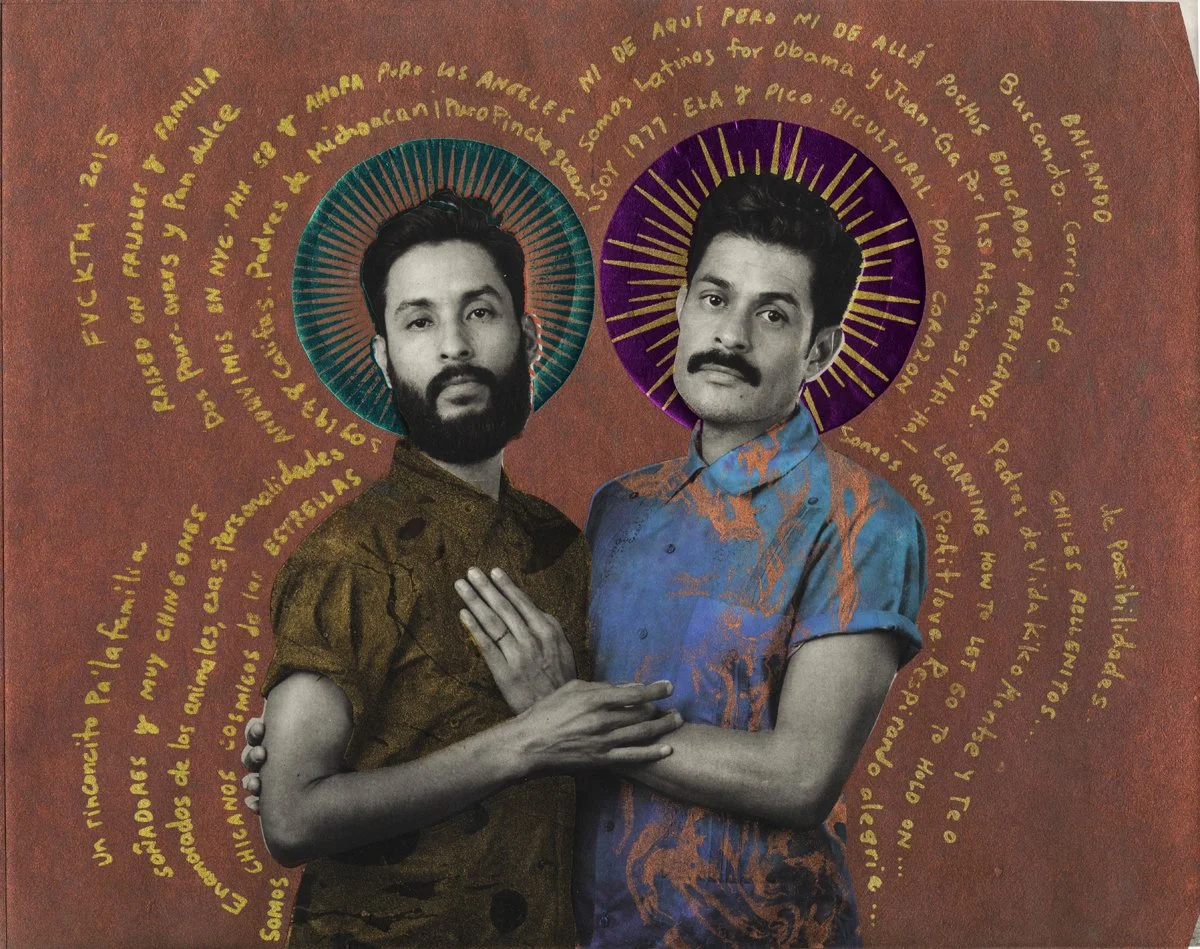

Let me introduce you to Gabriel García Román, an artist of many trades and the creator of Queer Icons, a portrait series featuring queer Latinx artists, activists, and community organizers. Through his series, Gabriel visually represents people of the QTPOC community as the saints that they are: folks who live in ways that bring life to others. Each portrait is unique and fashioned in the style of Catholic icons, with typical motifs of Catholic religious art – halos, metallic tones, elaborate frames, and carefully positioned hands. The process of making the portraits into icons is slow and requires much patience—a process Gabriel describes as a meditative experience. Through this careful process and final outcome, he honors the work of each saint, honors their being, and presents the poet/artist/activist in a beautiful, empowered posture.

His is a very intentional labor of love.

Queer Icons portraits by Gabriel García Román; photogravure with chine-colle. Clockwise from top left: Castro, Bayani & Candy, 2019; Mitchyll, 2014; Gabriela, 2018; and Carlos & Fernando, 2016.

Gabriel intended for Queer Icons to fill a gap in how the QTPOC community has (or has not) been represented in the art world and other media. This absence of representation became a personal and social concern for him, both in terms of his own identity as part of the QTPOC community and more broadly as well. Among those in his mind were queer young people isolated in small towns who might not have or see themselves reflected in people with whom they can identify or look up to—an experience he had firsthand. Gabriel came to his vocation, and to art school, later in life (late thirties). And while there, he noted that he never saw himself or his community “represented in any way—[not] in any of the art spaces, galleries.”

This lack of QTPOC community representation in both virtual and physical art spaces became the inspiration for the Queer Icon series, which aims to change the narrative. For Gabriel, not getting to have imagery “that looks like them” means not having art as a source that “gives them power.” And wanting to give people his art as a source of power is also part of why the people Gabriel highlights as icons are not high-profile folks but “everyday saints” doing their work on the ground.

“I don't want this to be a popularity contest,” he says, “where I want the big names who are in the media. No, I want the local person who started a kitchen for trans women in Harlem…Or, you know, somebody that's not necessarily getting all the media attention.”

In filling the representation gap, Gabriel intentionally uses the power of art to both humanize the QTPOC community in an unjust world and to empower those it marginalizes. He thus works painstakingly to capture the human dignity and the story of each person he photographs.

Gabriel on the making of Queer Icons

Gabriel speaks of his work as his practice. The meditation and intentionality that he puts into his practice imbues the icons with spirit. When he gets to witness people appreciating his art, he recognizes that they are not only receiving the spirit he has put into the work but also the power of the saints themselves. His intention for this encounter to, in turn, help draw out the viewer’s own power– a power that inspires Gabriel even further. Seeing somebody's eyes light up when they are before a Queer Icon motivates him to then do “the next one, and the next one…” Gabriel acknowledges the exponential growth of the project: “It started off as something very personal to me…[but] at this point, [it] has become a lot bigger, and it’s no longer my project – now it's my community’s project.” Because of such scale, the burden of “perfection” has not been an obstacle to his work. He embraces the practice, along with all the “mistakes” that may be involved, since they are part of what brings the work to completion– a concept many of us in the academy often have a difficult time embracing.

Gabriel on the practice of craft

In hearing Gabriel speak about his work—at once so personal to him but which he also holds with openness and easily gifts back to his community of inspiration—I’m struck by his groundedness. He embodies the very power he wants his Icons to convey to the world, and he is very clear about the community of accountability to whom he feels responsible. I covet the ease he seems to have with himself, and the focus and conviction with which he approaches his art. And yet a distinct “lightness,” both in his very being and in his art, also comes through.

His self-portraits (not part of the Queer Icon series) often show him floating or elevated as if ascending to the heavens. His groundedness is also his lightness, a connection he acknowledges. As he moved into his vocation as an artist, as he embraced his art as his practiced, and as he became increasingly comfortable with himself and the truth of who he is – neither from “here” nor from “there”—Gabriel came to know and embrace his own worth, and that, he says,

“is very similar to an ascension to the heavens…Knowing yourself, getting to know yourself, is definitely almost like going to paradise, because nothing that somebody could say can knock you down, because you know who you are, you know your worth.”

Knowing one’s worth and recognizing the worthiness of others, especially those who we dehumanize in society – personally, systemically, structurally – is very much what Gabriel’s Queer Icon series is about. I see how the work comes from his own sense of vocation, intention, and commitment to his community.

I connect this devotion with the ways that the Hispanic Theological Initiative (HTI) calls us to be true to our own sense of self and encourages us to bring that to our writing, even as we acknowledge all the complications that surround us. Just as Gabriel attunes to his “subjects,” we must similarly be attuned to ourselves and to one another so that we can keep on this road together, in the in-between spaces that are oftentimes our home as Latinx folks in the academy. We must stay grounded in ourselves and in community, so that we can also elevate.

Gabriel on the beauty of community, reflection, and struggle

View Gabriel García Román’s work at http://www.gabrielgarciaroman.com/.

COMING SOON…

St. Everyday (Part II): Mais Viva!

Dr. Xochitl Alvizo sums up Gabriel García Román’s visit to her Queer Theory class at California State University, Northridge and her students’ engagement with his work, along with the scholarship of Black trans feminist scholar Dr. Dora Silva Santana of John Jay College, CUNY.

Photo and animation: Gabriel García Román

Not Your Typical Devotional

HTI Scholar Jasmin Figueroa talks to activist/entrepreneur Crystal Cheatham about her work creating digital progressive Christian content

HTI Scholar Jasmin Figueroa talks to activist/entrepreneur Crystal Cheatham about her work creating digital progressive Christian content

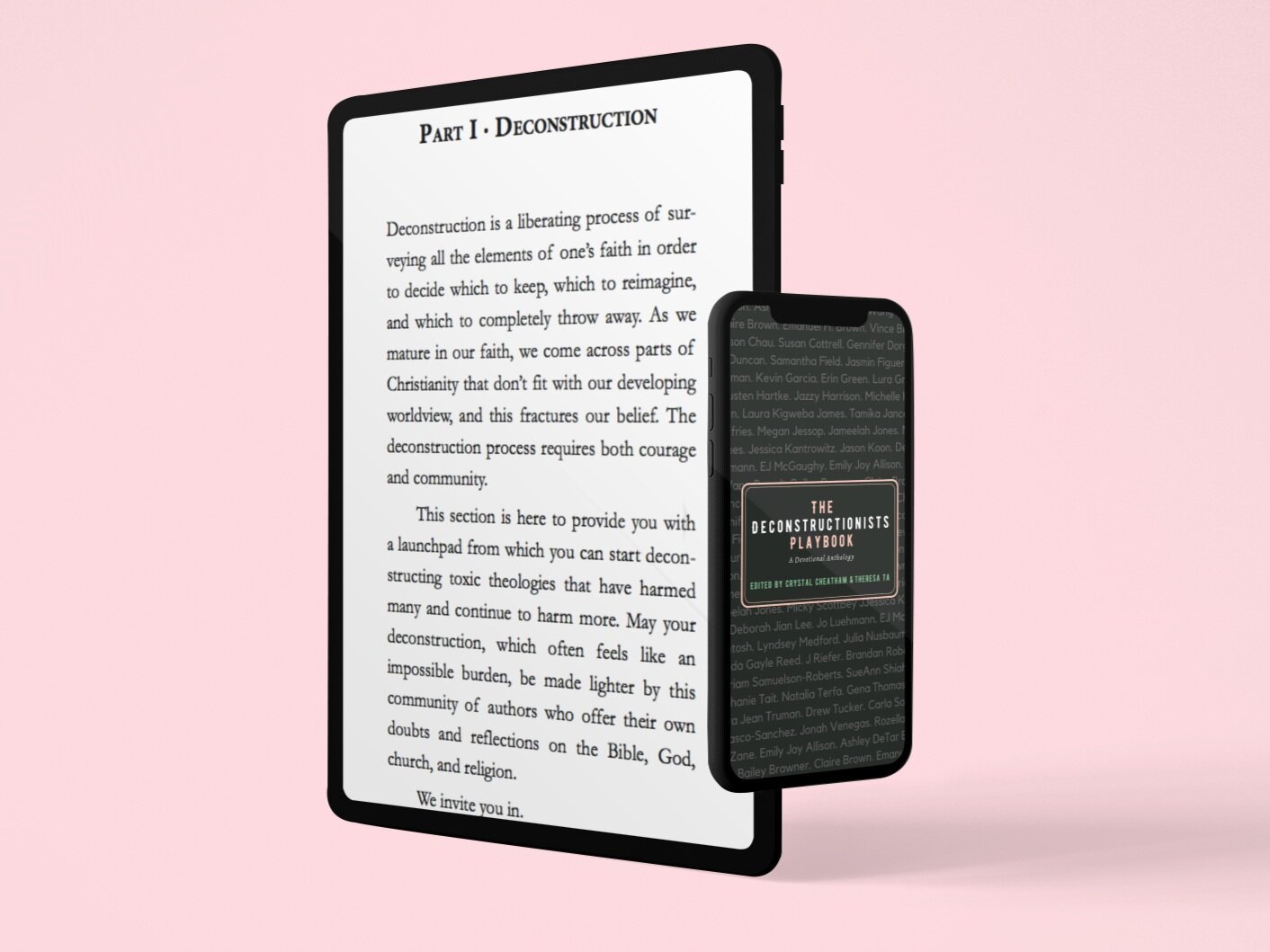

Promotional image for the ebook edition of The Deconstructionists Playbook (Bemba Press, 2021), edited by Crystal Cheatham and Theresa Ta. Image Courtesy of Our Bible App

Crystal Cheatham is an LGBTQ rights activist with a focus on religious liberty. She is founder of Our Bible App and co-editor of The Deconstructionist’s Playbook (Bemba Press, 2021), an anthology of devotionals by and for progressive Christians and people in Christian adjacent spaces. In this episode of OP Talks, Cheatham talks to HTI Scholar Jasmin Figueroa about the physical, emotional, and mental toll of working to create more inclusive Christian spaces. “We want to build community. We want you to find your community,” says Cheatham. “And when you start to deconstruct your faith, people look at you a little weird: ‘What are you doing? Are you a heretic? Are you going to hell now?’ So we want to be able to give [deconstructionists] a soft place to land.”

SAMPLE DEVOTIONALS

This is not your typical devotional. Until now, it has been extremely difficult to find devotionals, podcasts, and resources that aren’t overtly conservative in nature. Our Bible App supports the belief that spirituality is a spectrum and that faith is a journey. At its core, the holy texts were written to be inclusive of all of God’s creation, especially those on the margins. These devotionals are explicitly queer-affirming, anti-racist, pro-feminism, and encouraging of interfaith inclusion, bringing together a once fragmented community of spiritual wanderers.

-

Day 1 of 3: In the Image of the Divergent God

So God created human beings in his own image; in

the image of God he created them, male and female he created them. -Genesis 1:27 (NLT)Genesis, the first book in the Bible, tells us that at the beginning of humanity’s creation, God created us all in God’s own image. Yes, all of us. Not just the male, the cis, the heteronormative, the white, the able…or the neurotypical. All of us.

For too long those whose cognition, perception, and social styles have been seen as diverging from the norm, as somehow intrinsically flawed or broken, have been exempted from the Imago Dei – the image of God. Just like those with poor, black and brown, disabled, trans and queer bodies, we have been othered, even while some of us – those deemed useful – have been lauded for our gifts. The stories told about us are of a people who are, because of our brain wiring, somewhere on the margins of the Kingdom.

But Genesis tells us a different story. Genesis tells us, in unambiguous terms, that we are all created in God’s image. This is an entirely different reality from simply saying that God loves us all, or that we are all His/Her/Their children. To say that we are created in God’s own image means not just that we are like God but that God is like us.

That God, in all God’s spectacular rainbow glory, is a spectrum too. Neurodiverse. Thinking, perceiving, and relating in myriad wonderful possibilities. As autistic people, or people with ADHD, synesthesia, sensory processing disorders, dyslexia, dyspraxia, Tourette’s or any other form of neurodiversity, we are an integral part of the Imago Dei.

It would not be complete without us.

God in whose image we are created, today I remember that as a member of the neurodiverse community, I am beautifully and wonderfully made in your image. We are not broken, but beautiful; not flawed, but flawless; not Other but Beloved. Amen.

-

Day 1 of 6

Ecclesiastes 3

For everything there is a season, and a time for every matter under heaven:

a time to be born, and a time to die;

a time to plant, and a time to pluck up what is planted;

a time to kill, and a time to heal;

a time to break down, and a time to build up;

a time to weep, and a time to laugh;

a time to mourn, and a time to dance;

a time to throw away stones, and a time to gather stones together;

a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;

a time to seek, and a time to lose;

a time to keep, and a time to throw away;

a time to tear, and a time to sew;

a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

a time to love, and a time to hate;

a time for war, and a time for peace.What gain have the workers from their toil? I have seen the business that God has given to everyone to be busy with. He has made everything suitable for its time; moreover, he has put a sense of past and future into their minds, yet they cannot find out what God has done from the beginning to the end. I know that there is nothing better for them than to be happy and enjoy themselves as long as they live; moreover, it is God’s gift that all should eat and drink and take pleasure in all their toil. I know that whatever God does endures for ever; nothing can be added to it, nor anything taken from it; God has done this, so that all should stand in awe before him. That which is, already has been; that which is to be, already is; and God seeks out what has gone by.

Moreover, I saw under the sun that in the place of justice, wickedness was there, and in the place of righteousness, wickedness was there as well. I said in my heart, God will judge the righteous and the wicked, for he has appointed a time for every matter, and for every work. I said in my heart with regard to human beings that God is testing them to show that they are but animals. For the fate of humans and the fate of animals is the same; as one dies, so dies the other. They all have the same breath, and humans have no advantage over the animals; for all is vanity.All go to one place; all are from the dust, and all turn to dust again. Who knows whether the human spirit goes upwards and the spirit of animals goes downwards to the earth? So I saw that there is nothing better than that all should enjoy their work, for that is their lot; who can bring them to see what will be after them?

As I thought about how to talk about managing the dark and cold months of fall and winter, I was drawn to this passage. More than any other Scripture, this passage focuses me on the changing of seasons and on the very nature of time itself. God has “put a sense of past and future into our minds.” Isn’t that curious? What would it look like to live without that sense? Would we simply be focused on the present moment, oblivious of causes and consequences? That doesn’t sound all bad!

Sometimes, I think this is the way my dog lives—carefree and constantly curious. Still, even she has been conditioned by the past. As a meditator, I suppose that I get brief glimpses of “timelessness” where I am completely focused on the here and now, grounded in my body, and aware of the world around me. Those moments, however, are fleeting; if we are to take this passage seriously, those moments—refreshing as they are—ignore the God-given sense of time that we all possess for some purpose.

This chapter hints that time is a double-edged sword, giving both occasion for laughter and tears, love and hate, birth and death. At one moment I can be marveling at the ways that my children are growing and be caught off guard by my own mortality in the next . This is the “gift” of time that has been placed within us. It tells us where we’ve come from and where we’re going. And this gift allows for us to do the critical work of storytelling and meaning-making.

As humans, meaning-making is our business. We want to know that our struggles have purpose. We want to know that our pain can be redeemed. It’s when life slows down that we begin to ask ourselves why things are the way they are. This questioning is a good thing. It is part of the work we are called to do.

The work of reflection is critical to our spiritual lives. It is rare that we give ourselves the time and space to do such work, yet it is critical if we are to gain understanding of ourselves, our neighbors, and our world. Writer Brigit Anna McNeil wrote the following about the coming of winter months:

“This is a time of rest and deep reflection, a time to wipe the slate clean as it were and clear out the old so you can walk into spring feeling ready to grow and skip without a dusty mountain on your back & chains around your ankles tied to the caves in your soul.

A time for the medicine of story, of fire, of nourishment and love.

A period of reconnecting, relearning & reclaiming of what this time means brings winter back to a time of kindness, love, rebirth, peace and unburdening instead of a time of dread, fear, depression and avoidance”

My hope for these next few days is that this season can go from being a time of fear, depression, and avoidance to a time of love, rebirth, and peace. I hope that you will make the space necessary to do the deep reflection for this complicated time of year.

-

Day 1 of 7: Introduction

“You are the light of the world. A town built on a hill cannot be hidden. Neither do people light a lamp and put it under a bowl. Instead they put it on its stand, and it gives light to everyone in the house. In the same way, let your light shine before others, that they may see your good deeds and glorify your Father in heaven.”

—Matthew 5:14-16

Evangelism has always been a dicey topic among progressive Christians. Many churches, solely focused on preaching the gospel, seem intent on forcing the Bible down people’s throats and preach the importance of conversion, of convincing people to commit their lives to Christ. This mindset is reflected in preachers on street corners, harassing passers-by and telling them they will go to hell unless they convert. Historically, the Western church has used the gospel as a reason to commit atrocities, like the Crusades and colonising countries in the name of God. Missionaries banned people from speaking their own languages, forcing them to learn the Bible and reject their cultures in order to adopt the religion of their oppressors. For this and many other reasons, the whole concept of evangelism rubs me the wrong way, especially since growing up it was beaten into my head over and over again that the most important thing in our lives was to “bring people to Christ.” It feels manipulative, heartless, as if we care more about “bringing God glory” than about respecting the basic humanity of others. The idea that God wants Christians to treat people that way seems abhorrent to me. And if that was the God who I believed in, I wouldn’t want to be Christian.

Luckily that’s not the God of the Bible, and not my God. My God is the God of the oppressed, who loves all people and wants a relationship with us. But They don’t want us to be coerced into it. The whole point of the Bible and the thousands of years of reaching out to us and then sending Jesus to live among us is that She cares about us and wants to know us as a friend, not as some tyrant. That’s why if we want to keep our faith, we need to rethink the way we understand the gospel, go back to God’s word and realize how God really wants us to share Their love with people. In Matthew 5, among other famous sayings of Jesus, He talks about how His followers, God’s people, are meant to be like a lamp on a stand or a lit-up town on a hill, a metaphor which means that how we act should reflect God’s goodness and draw others to us. This is nothing like the evangelism and conversion we’ve been exposed to, where we go out and try to indoctrinate anyone we can get our hands on. Over the next few days, we’ll be looking at examples in the Bible of how this whole light on a stand thing worked, and think about how we can preach the Gospel without hurting the very people we want to help.

Take this time to think about what you’ve been taught about evangelism in the past. Did what you learn emphasize the value of every person regardless of their conversion to Christ? Or did it fall more under the forceful notion that they needed to learn about God no matter what or they’re going to hell? Either way, dwell on this, and consider the God you believe in. What do you think is the best way to share that God with others?

-

Day 1: What Is Spiritual Bypassing?

There is a time for everything, and a season for every activity under the heavens; a time to weep and a time to laugh, a time to mourn and a time to dance, a time to scatter stones and a time to gather them.

—Ecclesiastes 3:1, 4-5

Spiritual Bypassing is a term first coined by John Wellwood in his 1980s text, Toward a Psychology of Awakening. He defines spiritual bypassing as “spiritual ideas and practices to sidestep personal, emotional ‘unfinished business,’ to shore up a shaky sense of self, or to belittle basic needs, feelings, and developmental tasks.”

There is sure to be a season in our lives when we have manipulated spiritual practices to avoid engaging with our emotions, or at least know of those who have.

Manipulating spiritual practices to avoid confronting difficult emotions can take many different forms.

Wellwood offers the example of those who go on spiritual retreats to escape reality, and then return with a sense of enlightenment; on retreat, they escape a reality that asks them to confront their emotions. Not too long after returning, however, they are often triggered by the very thing they attempted to escape on retreat in the first place.

At its best, spiritual practices call us to be present and better our awareness of our self, of others, and our sense of placement in the world. At its worst, spiritual practices act as a defense mechanism or distraction and can actually disconnect us from our emotions and others.

As we practice eager waiting during Advent, we find ourselves anticipating more than just the birth of Christ. We are in eager anticipation for a vaccine, to reunite with loved ones, to let out a deep sigh when this pandemic is over. We have globally experienced a pandemic that has killed hundreds of thousands of people; with that, we have experienced global, communal grief. We grieve our loved ones who have died, lost experiences and celebrations due to self-isolation, the anxiety that undergirds daily life, the regular police shootings of BIPOC, civic unrest and uncertainty; the list goes on and on. It is tempting to lean on spirituality as a distraction from reality. As pandemic depression collides with seasonal depression in the winter months, any escape from reality can seem welcoming.

When we lean on spirituality as a distraction mechanism, we not only block ourselves from engaging with our emotions, we also deter others from expressing theirs. When we do this, we distance ourselves from our loved ones who attempt to express their grief and anxiety. We fail to be present with ourselves and with them.

One of the ways Christian people spiritually bypass their own emotions and others' is by relying on scripture that overemphasizes the good and fails to address the negative. We use scripture to brush off one another’s pain and hurt instead of engaging with it. When we use scripture to bypass an individual’s grief, we fail to engage and be present with them.

Often, scripture is taken out of context to ‘comfort’ someone who expresses anxieties and trauma. However, by putting the scripture in context, we come to know how it calls us to be present with one another in times of loss and grief.

Orient our hearts towards those who grieve this Advent season; let us recognize and engage our own grief and know it is done in community.

The Our Bible App platform offers the largest compilation of progressive faith-based content.

The Deconstructionists Playbook (Bemba Press, 2021) comprises selections from devotionals that have been published by Our Bible App.