Xitlali Zaragoza, Curandera

Reyes Ramírez presents a story excerpt from his debut collection The Book of Wanderers

La Curandera, ca. 1974, hand-colored etching and aquatint on paper by Carmen Lomas Garza, artist and activist who was central to the early Chicano Movement. Garza chronicles intimate daily life scenes based on remembrances of her own childhood in Kingsville, Texas, in the 1950s and 1960s. Source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Tomás Ybarra-Frausto, 1995.50.60, © 1974, Carmen Lomas Garza

FOREWORD

Reyes Ramírez presents a story excerpt from The Book of Wanderers (University of Arizona Press, 2022), with images curated by Open Plaza. The collection of short stories opens with a foreword by the publisher’s Camino del Sol series editor Rigoberto González (Rutgers University, author of The Book of Ruin):

Reyes Ramirez is not a liar but a truth teller, offering us a blunt glimpse into the lives of undocumented immigrants…Connecting this gathering of poignant stories is the grief or absence felt by the protagonists, like Xitlali Zaragoza, the superhero curandera, who has a prayer and an herbal concoction to ward off everyone’s otherworldly menaces but is unable to treat the heartbreak of her estrangement from her daughter…Reyes, an avowed Houstonian, makes a foundation of his beloved city and home state, where most of the collection is set, inspired by Texas’s own complicated historical timeline.

Xitlali leans on the bar, five hours into her shift at her other job as a Mexican-restaurant waitress.

She massages her temples and can feel the bags under her eyes deepen. A customer waves her over to his table to pay the tab for four margaritas and three cervezas, drunk and alone on a Tuesday at 5 p.m. He has a sad aura about him, thick and gloomy, colored like cough syrup.

“Ah-kee ten-go el dee-naro,” el gringo says.

“Awesome. Thanks,” Xitlali responds.

He hands over cash and barely leaves a tip. Xitlali yawns and doesn’t bother to offer a blessing, as much as it seems he could use one. Dios mío, prayers and alcohol are the two most abused inventions in human history. Any method to not completely accept this reality will do. That’s when the phone in her pocket vibrates. She walks outside and answers.

“Curandera Zaragoza, we have an assignment for you. Es urgente.”

“It can’t wait?”

“We tried calling other curanderas, Xitlali. No one else wants to touch this.”

“Why is that?” Xitlali asks, resting against the brick exterior of the Mexican restaurant and watching out for her manager.

“This client is gay. The other curanderas say they cannot save a sinner from himself. We know it’s short notice, but can you take it?”

“Ay, pues…Of course. If evil does not discriminate, why would I?” Xitlali says as she pulls her notepad from her back pocket. Desgraciadas. “Dígame.”

“José Benavidez has been experiencing a haunting. Says that every night, while walking home from work, there’s a presence that follows him. Won’t say what exactly. Says he might encounter it again tonight.”

“Has there been physical interaction?”

“No.”

“Bien,” Xitlali mutters, scribbling onto her notepad. She can sense an energy from his name already, tense yet weakened by anxiety. Pobrecito. “I’ll be there as soon as I can.”

“Bien, bien, bien. Mira, the code is #1448 to get into the gate. Complex is called Cherry Pointe. Apartment 13.”

“Gracias. Que Dios la bendiga.”

“Que Dios la bendiga, Curandera Zaragoza.”

After closing all her tabs and sneaking out of the restaurant an hour early, Xitlali jumps into her 2004 Ford Taurus—over 138,000 miles on the engine—and leaves for the complex fifteen minutes away. The air is thick with blaring lights like cheap, knockoff suns. Every stoplight turns red, as though trying to slow her from reaching José Benavidez. Xitlali uses these short pauses to sort through her messy back seat and work bag, both littered with clothes, various documents, and crumbs from the many dried herbs she uses day-to-day. I gotta make time to sort through all this shit. Always something. Juan Gabriel sings sadly through the radio about the sadness of desire.

As Xitlali pulls up to the apartment complex’s box to enter the code, she can feel music and taste food grilling. She’s so hungry, she can’t think of the code. Notepad out, she looks for the page, flipping through notes on other cases she’s solved this last week.

Mayra Montevideo –Heights –Curse from a Lover –Space purified with Sage, Oración, $40.

Salvador Trujillo –Midtown –Rashes from Bad Energy –Recommended oils and scents, Referred to Curandera Gabriela Herrera who specializes in yerbería, Oración, $20.

Muriel Gonzáles –East End –Fevers –Blessed her belongings and space, Oración, $45.

Xitlali gains some confidence, remembering she solved these cases and many more written down in her other notepads scattered about her car’s floor. This will be no different…but I have a bad feeling.

As she parks, she sees where the sounds and smells are coming from. In the apartment complex clubhouse is a quinceañera. Xitlali can tell from the strobe lights, cumbia pounding out from speakers, the drunk uncle standing before a grill loaded with carne asada, and a young woman in a light blue dress with rhinestones lined vertically on the bustier, sequins and pearls in a swirl design on her belly, the gown raining down the rest of her body like thin tissue. Her silver crown peeks out of her hair, styled in a bouffant. She’s gorgeous.

A grand sadness yearns out of her heart. Xitlali hasn’t spoken to her own daughter in twelve years. She tries not to think about it. There used to be a picture of her daughter on her dashboard, but Xitlali took it down a while ago so as not to be reminded of that failure. Bad energy for the job. She looks at the spot where it was, a patch of plastic darker than the rest of the dashboard. Twelve years. Not a word. I can’t do anything about it right now. Twelve years, carajo. Her tire bumps into the curb which wakes her from her trance.

What makes Xitlali special is that she goes deeper than most curanderas. Rather than just addressing the symptoms of a haunting or bad energy, she investigates what caused the problem.

Her clients love this about her.

Teresa Urrea laying hands on a baby, 1896, El Paso, Texas, where she treated approximately 200 people per day. Photo: Charles Rose. Source: Serman, Jennifer K. “Laying-on Hands: Santa Teresa Urrea’s Curanderismo as Medicine and Refuge at the Turn of the Twentieth Century,” Studies in Religion / Sciences Religieuses Vol 47, Issue 2, 2018.

She finds apartment 13 and knocks.

She can feel a headache coming on from hunger, and her ankles are swollen from standing around all day.

“Yes?” a man yells from behind the door.

“Xitlali Zaragoza, curandera.”

Locks clink behind the door before it opens.

“Come in, please,” the man says. He’s light-brown skinned, in his early thirties.

“José?”

“No, he’s my partner. I’m Rolando. I’ll let him know you’re here.”

There are unframed photographs all over the walls, ranging from portraits to landscapes to abstractions, some color, some black and white. One in particular stands out to Xitlali: a shoulders-up portrait of a young man. He stares at the camera—beyond it, at you—and his eyes convey a deep lethargy or an accepted sadness, if there’s a difference. Xitlali stares into the picture, entranced by his eyes, which are unblinking, watching ceaselessly. You cannot return the gaze. His gaze has power over you. That is its beauty.

“Ms. Zaragoza, you like my self-portrait?”

Xitlali looks at the young man in the picture and the young man now standing before her. They are the same person, except that the one standing right here has an aura that isn’t as strong.

“Oh, yes. I love this piece,” Xitlali says.

“I took it after I had a nightmare,” José says, rubbing his neck with his right hand.

Xitlali pulls out her notepad and pen. “What is this dream?”

“Can we sit down?”

“Yes, of course. But the dream. Dígame.”

“Why? It’s nothing really.”

“If you want me to help you, you must answer my questions. Everything I ask, say, and do is to help. ¿Entiendes?”

“Yes, of course. I’m sorry.”

“Don’t be sorry. Go on.”

“It starts with me in a room, surrounded by mirrors. I’m wearing jeans, a white shirt, and these really tall high heels. I’m staring at myself. I can’t leave or move, and I work into a panic. Then my father appears and looks right at me. I can’t talk. I can’t do anything. Then I wake up. It’s funny—in that self-portrait, I’m trying to make the face he made in the dream.”

“Why do you think you have this nightmare?”

“Well, because it really happened. My dad walked in on me wearing heels as a child and gave me this angry look. They really didn’t mean anything then, the heels. Just kid stuff, you know. It’s the look he gave me. In the dream, it’s more melancholic, but in reality, it was rage. Every time I have that dream, it reminds me of how disappointed he was in me.”

“Was?”

“We stopped talking when I came out, and he died a few years ago. We never really reconciled,” José says, his eyes welling up. José’s partner rubs his back with one hand, but Xitlali can sense anger and helplessness form within Rolando.

Xitlali feels the same sadness from earlier creep up within her. He must feel awful for never reconciling. It causes bad energy. I know the feeling. Shit, not right now, Xitlali. She concentrates on the job. There’s a lingering feeling of regret haunting José. If I can find a connection, we can finish this quick.

Rolando speaks. “This all just seems like a lot of nonsense.”

“Whether you believe it or not, this is causing tangible pain and dislocation. You dismissing it only feeds the evil power. Your bad energy is wasting our time,” Xitlali says. Rolando is startled and places his hand over his chest.

“I’m sorry, Ms. Zaragoza,” says José. “Rolando doesn’t believe any of this.”

“Ya. It’s okay. Look, take me to see where this happens. Then I can make an accurate assessment.”

As they go to her car, Xitlali sees the party still going. She sees the birthday girl hiding behind a sedan, drinking a beer. She and the girl meet eyes for a second. Xitlali looks away.

You only get one quinceañera.

La curandera y su jardín [The Healer and Her Garden] (1998), bronze sculpture relief by Reynaldo Rivera at The Healers Garden, ABQ BioPark, Rio Grande Botanical Garden, Albuquerque, New Mexico, 2013. Photo: Zruda

She drives José to the movie theater where he works, a few blocks away.

Its bright lights fight with the night sky long enough to attract families, couples, and loners to sit in silence together and watch. José explains that he works as a ticket attendant, sometimes as late as 1:30 a.m. He walks home alone after, in the odd time before the bars set the drunks loose but after a point of reliability for METRO buses to still be running. The homeless sleep under the bus stop kiosks. Xitlali parks in the back of the theater lot, close to the street, and directs José to lead her through his routine. She yanks her heavy work bag from the back seat, and the motion cracks off a shard of pain in her shoulder.

They walk along Westheimer, a long, long street that always smells of burnt rubber and carbon monoxide, occasionally interrupted by the aromas of foods from all over the world: Mexican, Japanese, Indian, Brazilian, Vietnamese, Chinese, Guatemalan, etc. Passing cars honk and muffled strip-club music whispers through the streets. The streetlights produce a yellow glow. As Xitlali walks, she feels the looming sensation that a truck could swerve into them at any minute, or a car could pull up and drunken voices from within could call them spics, dirty Mexicans, job stealers, illegals, then step out of the car and ruin them. A lot of dark energy here. White bicycles and crosses dot the sidewalks, memorials where Houstonians were run over while cycling. Conduits through which the living speak to the dead.

“Why doesn’t Rolando pick you up from work?”

“He’s a bartender,” José says. “So, I walk along this big street, and then I get this feeling that something is following me. I get closer to home, and this feeling of dread fills me.”

“And?”

“This little stretch of road that connects Westheimer to my apartment. This is where the thing starts to follow me.”

“Have you ever seen it?”

“Yes. It’s hard to describe,” José says, rubbing his head with his hand, trying to stimulate thought.

“Look, I know it’s hard, but I have to know what it is. Otherwise, I won’t be able to help you.”

“Ok,” José responds, massaging his left bicep with his right hand.

This smaller road only goes a quarter mile, and it wallows in a murky darkness. Garbage fills the ditch alongside it. The sidewalk is cracked with no indication of future repair. There’s no more sound from Westheimer.

“It’s when I walk on this sidewalk that I hear them—these footsteps—clack-clack-clack.” José illustrates by slapping one palm into the other.

Xitlali can sense the fear running up his spine. Blood rushes into his head, reddening his ears and cheeks. “And what do you see?” she asks.

“I’m going to sound insane.”

“Mira, I’ve seen and heard crazy. Dígame.”

“I-I look back and there’s this . . . this dog. A brown-coated, white-bellied pit bull with a human face . . . this face of extreme grief. It follows me, and it’s crying. What’s making the clacking sound are the heels it’s wearing. Bright red heels. It can walk perfectly in them, on all fours. It’s sashaying, dancing even, like it’s mocking my fear.” A sheen of sweat gleams on José’s face.

Xitlali nods. “Yes. I can feel a dark presence here. Let me inspect the area.” She pulls a flashlight from her bag and uses it to illuminate sections of the sidewalk, like a prison warden searching for an escaped convict. There it is: another white cross, surrounded by fast-food wrappers, cigarette butts, and tall weeds. Xitlali approaches it and feels her pulse quicken, skin becoming cold. Yes, this is it. The cross has something written on it, smudged by time and rain: Gabriel Méndez. Xitlali is light-headed from the hunger and humidity and finds it harder and harder to think. Virgen, ayúdame, porfa. Dame la fuerza.

“Pues, José, I think I know what’s happening. There was a death here—an unresolved one. Many dark feelings have lingered here and grown. It seems someone mourned this death for a moment but not enough to give this spirit peace,” Xitlali explains, rubbing her temples to ward off the forming migraine. “Could be because people around here move a lot. Or they lost hope.”

“What does that have to do with me?”

“You’re already spiritually fatigued and carry traumas. That makes it easy for this spirit to feed off your fear and pain,” Xitlali says. I know, joven, because I, too, have a past to reconcile. Who am I to lecture anyone on that? “You being tired after work and the fear the night instills in you make it easier for this spirit to take advantage. It’s why it manifests into our reality, wearing the heels from your nightmare. It knows what gets to you. I will give this spirit peace. However, you have to make peace with whatever is happening in you, or it’ll only be a matter of time before another spirit clues in on you. I can’t help you with that, but I know you can do it. You must. Do you understand?”

“Yes. I understand,” José says.

“Bueno. I need you to help me purify this space.”

Xitlali takes the holy water from vial on her neck and sprinkles it over the cross. She pulls some of the weeds out and collects the garbage from the ground around it. José, as instructed, places candles around the cross and lights them. Xitlali gives her minimal yet honest prayer:

May God bless this space,

La Virgen ayúdanos,

porfa, forever and always,

con safos, safos, safos.

She takes the sage from her other necklace vial and burns it to emit a fragrant smoke. She hands a piece to José, then makes the sign of the cross on herself, thumb touching left shoulder, right shoulder, forehead, and heart, then a kiss to seal it all in.

When they’re done, Xitlali can sense José’s energy lift from his new peace of mind. She has him sign forms and gives him her bill of sixty dollars.

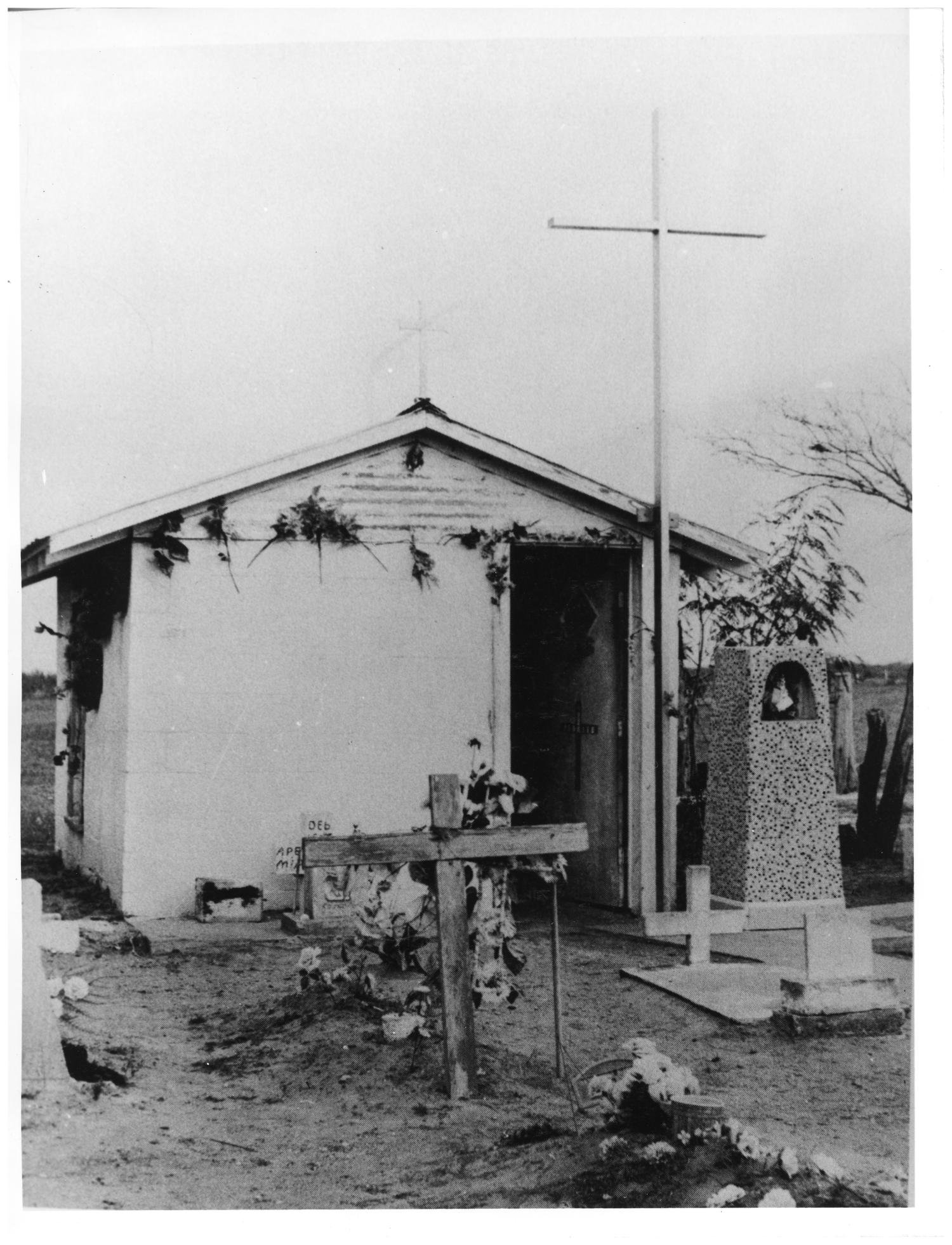

Shrine to the folk saint and "el mero jefe" [absolute chief] of curanderos Don Pedro Jaramillo, n.d., Los Olmos Cemetery, Falfurrias, Texas. Source: University of North Texas Libraries, The Portal to Texas History; crediting Marfa Public Library.

Later, after she’s dropped off José at his apartment complex, she sits in her car for a while to write notes.

I see more and more of these crosses along the streets. How many have been forgotten? How many spirits linger within the streets, within their cracks? As more of these traumas happen and stay unresolved, the more these restless spirits will roam within our reality and demand our attention, using our fear and anger. This spirit was more grotesque than usual and knew José’s traumas, even though José did not seem to know the name on the cross. Are these spirits becoming more desperate to agitate us?

Xitlali reaches down to take off her work shoes but is interrupted by another call. She sighs before answering.

“¿Bueno?”

“Curandera Zaragoza, we have another assignment.”

Xitlali reaches down to take off her work shoes but is interrupted by another call.

She sighs before answering.

“¿Bueno?”

“Curandera Zaragoza, we have another assignment.”

“I can’t. I’m exhausted,” Xitlali says, running her fingers through her hair.

“This is an emergency. You’re the only one who can handle this case.”

“Wildly inventive, sometimes melancholy, and possessed of an abiding sense of compassion and justice, Reyes Ramirez’s collection is inhabited by a group of unforgettable wanderers exploring and redefining familiar, strange, and future worlds.”

—ire’ne lara silva, author of Cuicacalli / House of Song