Turn Back and Look

Seminarian Amanda Calderón gives voice to Lot’s Wife

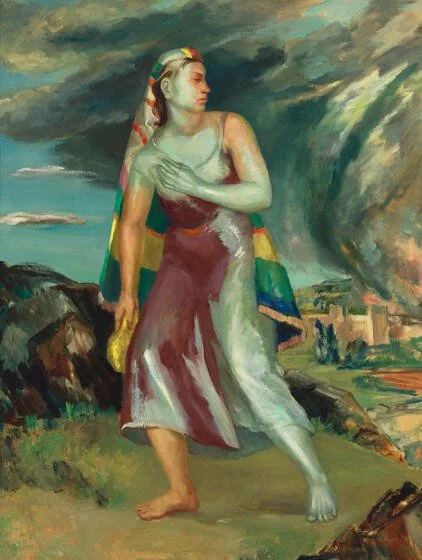

Pillar of salt known as Lot’s Wife on Mount Sodom, near the southwestern part of the Dead Sea in Israel, 2013. Photo: JoTB

The following is based on a sermon delivered by third-year MDiv student Amanda Calderón at the Princeton Theological Seminary Chapel in Princeton, NJ on 31 January 2023.

At the beginning of this year, I was blessed to go to Brazil for a J-term travel course titled “Towards Understanding Other Cultures,” and it is an understatement to say that the things I experienced changed me.

And out of all the lessons we learned, I kept coming to the realization that all the theologizing and all the book reading in the world is futile if, when we put the books away, nothing in us changes.

If our hermenéutics are still serving to silence women.

If our churches only invite–but do not have–welcoming structures for Black and Brown people.

If we, along with our churches, are still silent to the injustices of the world.

If we push away those who Christ would’ve held closest.

Then, theologizing means nothing. To simply learn information without its application to our lives is an incomplete learning process. So, I urge us, we who are in this place, as we are doing this learning and theologizing, to not let our research and our knowledge hinder us from seeing the humanity in people.

In Brazil, we had a woman speaker—Barbara—who said, “Academia is important, but the moment it stops me from being able to speak to the least of these, it becomes useless.”

A perfect example of this is found in Genesis through the narrative of Lot’s wife turning to stone. As I was doing my research/exegesis for this meditation, I did what any good seminarian does and went straight to devotionals and commentaries. But what I found was condemnation. Most of them are titled “don’t look back” or “don’t look away from your blessing.” And every single condemner had an articulate defense of why we should not be like Lot’s wife: Don’t look back to your old life of sin. Every single one proposed that God was punishing her and that it was her fault.

I am not interested in determining who in this story is wrong and who is right. I am interested in allowing this woman to have a voice and tell her own story after being silenced by those who ignore the complexity of her decision to turn back. Lot himself was hesitant–to the point that angels had to drag him out by physical force–and yet, one spouse is celebrated for his bravery, and the other is condemned for her grief.

In this narrative, Lot’s Wife is not the first to show hesitation.

We don’t know her name, and yet theologians and spectators of this narrative feel the authority to tell her story and to do so in a negative light.

We must make sure we don’t do that as those with theological education do.

May we not tell people's stories for them in order to condemn them.

We must place names and stories to faces.

And some of you may be asking yourselves, “Well, how else am I supposed to view her other than as a sinner or as someone who disobeyed God?” I have two answers.

The first is:

We are all sinners, and we all have disobeyed God, so we view her essentially as we would view ourselves–as flawed humans.

The second answer is this:

When I see Lot’s wife, I don’t see a sinner. I see a woman who is mourning her family, friends, land, and home. I see a woman who has the guilt of leaving, knowing the destruction that is coming.

In Lot’s Wife, I see the immigrant story. I see my parents, my aunts, my uncles, my cousins, my grandparents, who also have had to pack their entire lives and grief into suitcases to leave their homes behind for the betterment of their families.

Lot’s Wife was not just saying goodbye to a place but to her home. She was saying goodbye to the visions she had had for her family, to the dreams she had had for her daughters, to their friends and family members.

In Lot’s Wife, I see my Black brothers and sisters who have been systematically and routinely silenced in various ways not just—not just by society, not just by the church, but also by the very theological institutions we attend.

I see the queer people whose very personhood is condemned and punished to silence.

I see myself as I deal with the grief of wanting so desperately to look back at my life before God called me to sacrifice my plans for God’s.

I see Christ who, instead of looking toward His celestial kingdom, let His body be crucified and consumed, because He just could not leave us behind to be destroyed.

I’m not disregarding or denying that Lot’s Wife went against a direct order from God. I am not saying to go against God. Do not go around up and down Nassau Street, saying, “Yea, Amanda said to sin and break the ‘rules”—that’s between you and Jesus. But what I am saying is to not let our stories be told for us and, similarly, to not tell others’ stories for them. To not feel guilty about the complexity of our decision-making and the complexity of our lives–but also knowing that, if we create space for complexity, we must also create space to be accountable for our actions.

What I am saying is that, as long as we do not compromise God’s promise to our lives, we shouldn’t feel shame in wanting to look back on the things we love. God made us human so that we can feel, experience, and wrestle with our lives and with God. I am not arguing about the righteousness of her actions–that’s between her and God, just like yours is between you and God. What I am arguing for is:

The validity of her feelings and of her pain.

The validity of her personhood.

The validity in her capability to tell her own story.

The validity of her grief.

But most importantly, I’m arguing that God’s intention was not for her destruction. Were that the case, the angel would not have held her hand and dragged her out with the rest of her family. And I’m not just arguing for Lot’s Wife or for myself; I’m arguing for every single person. You are so much more than your mistakes. You are so much more than your grief and your pain, and you are so much more than the connotations and opinions of others.

You are allowed to be complex.

You are allowed to grieve.

You are allowed to love.

Students of color, hear me when I say that you are allowed to live in the entirety of who God has called you to be, even in a place that silences. So, as we go through our seasons, let us remember that what we are doing in this place–the seminary–is important. Theology and theological education are very important. But their importance does not come from the knowledge you have in your head. Their importance is found in the praxis, in the application, and most of all, when we use this knowledge for the advancement of the kingdom of God.

Let us allow ourselves the space for our divine given complexities.

Let us be slow to judge and eager for human connection.

Let us create space for people to tell their stories.

Let us use the gift of theological imagination.

Let us be complex.

Let us struggle and grieve.

Let us love.