The Harlem Lynching Tree, with Poems for Alma

Taylor Alexis Baker presents inspired excerpts from her novel in progress

Red-tailed hawk (Buteo jamaicensis) perched atop the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, Amsterdam Avenue between W. 110th & W. 113th Streets, New York City, 2007. Photo: Robert

AUTHORS’ NOTE

Juneteenth was the day of liberation from slavery in the United States. To this day, we still wear the shackles of our ancestors in an unstoppable fight for true freedom. The day when we can walk this earth without being judged by our skin color but as human beings has yet to come. My writing will see to it that this day will come.

“The Harlem Lynching Tree” is a work of fiction that explores Harlem, religion, and Black and Brown communities through current events and the eyes of famous Black writers and philosophers. I wanted to answer the question: “What would past writers and theologists think of modern-day Harlem, and what would they tell us in moving forward?” I drew from many articles, videos, and art works by these thinkers to make a literary collage of their works as a backdrop for my Harlem [imagery throughout this version curated by Open Plaza]. The story includes poetry dedicated to Alma Reyes Martínez, the main character who represents all of us. I hope to finish writing this story as part of my MFA thesis at City College-CUNY, have it published, and share it with the community as a way to raise awareness about racial violence on Black and Brown women, and its impact on our lives.

—Taylor Alexis Baker

New York City, June 2021

At the end

In the wake of an oncoming and

Belittled life, the clouds come marching

In over the now heated pavement of the last driveway

Before the clift. The rays of sunshine that lost their fine luster

And carried more starlight than the summer sky scurry away.

The people come in droves, drenched in despair and somber black

Dressings. Your favorite color, dampened and velveted over when the rain stops

By. And they cry. Why do the good ones always die. The summer showers end the service

On an unkept note. In rhythm, the mourners empty out the spaces you still fill and borrow each

Other’s broken chuckles. No one knew that today would be your last day to bring them

Together. To a tune, it all ends when the driveway becomes barren, and the bustling city

Reappears in someone’s rearview mirror. We return to a life without you trying to change

The world. And we cry.

Pair of Ridgeway's hawks (Buteo ridgwayi/gavilán dominicano), Los Haitises National Park, Dom. Rep., 2009. Photo: Ron Knight

Alma Reyes Martínez was my best friend for approximately two hours and 45 minutes.

In less than five minutes, after what I thought would be the best friendship I’ve ever had, she was dead. I still think about what happened all the time. In an instant, someone like Alma, who deserved more from life than the lemons hurled at her, was gone. Somehow, I feel the need to avenge her. Somehow, Alma Reyes Martínez will be the one to save me from drowning in this river we call freedom.

I’ve started going to church more often. By myself. My mother’s happy that I’m spending more time with the lord. She doesn’t realize that I’m further away from God than I’ve ever been, that I’m hoping for him--or something like him--to come sit with me in those empty pews. After what happened, I’ve thought long and hard about my relationship with Christianity. I’m already the model Christian, one who doesn’t sin as much as the other sinners. And, thankfully, through my undergraduate course in African American studies, there are plenty of people I can turn to for solace.

James Cone is one of my favorite theologians. Yes, I have a favorite, because his works made me aware of one thing: I’m a black woman worshiping a whitewashed God. I recall a statement Cone once made in an interview about White theologians going something like, “I think their silence stems partly from a distorted understanding of what the Gospel means in a racially broken world.”

The words “racially broken” and “Gospel” being in the same sentence is ironic. Was this religion not founded on the ideas of a man dying for people out of love? People he did not know personally, who did not look like him? I never understood how anyone could look love in the eye ensnared with such hate.

I’d never thought I had this conflict in me about what God is until I saw Alma die at a Black Lives Matter protest on 110th Street in Harlem a week ago. What did white Jesus need from her that he had to take her away from me? Away from this world? She stood so high up and yelled so loud.

“My life matters!”

Yes, Alma. Your life did matter.

So when that car—that nasty red car with the Nazi flag in the back window—hit you, then rolled over you, it made me a new person.

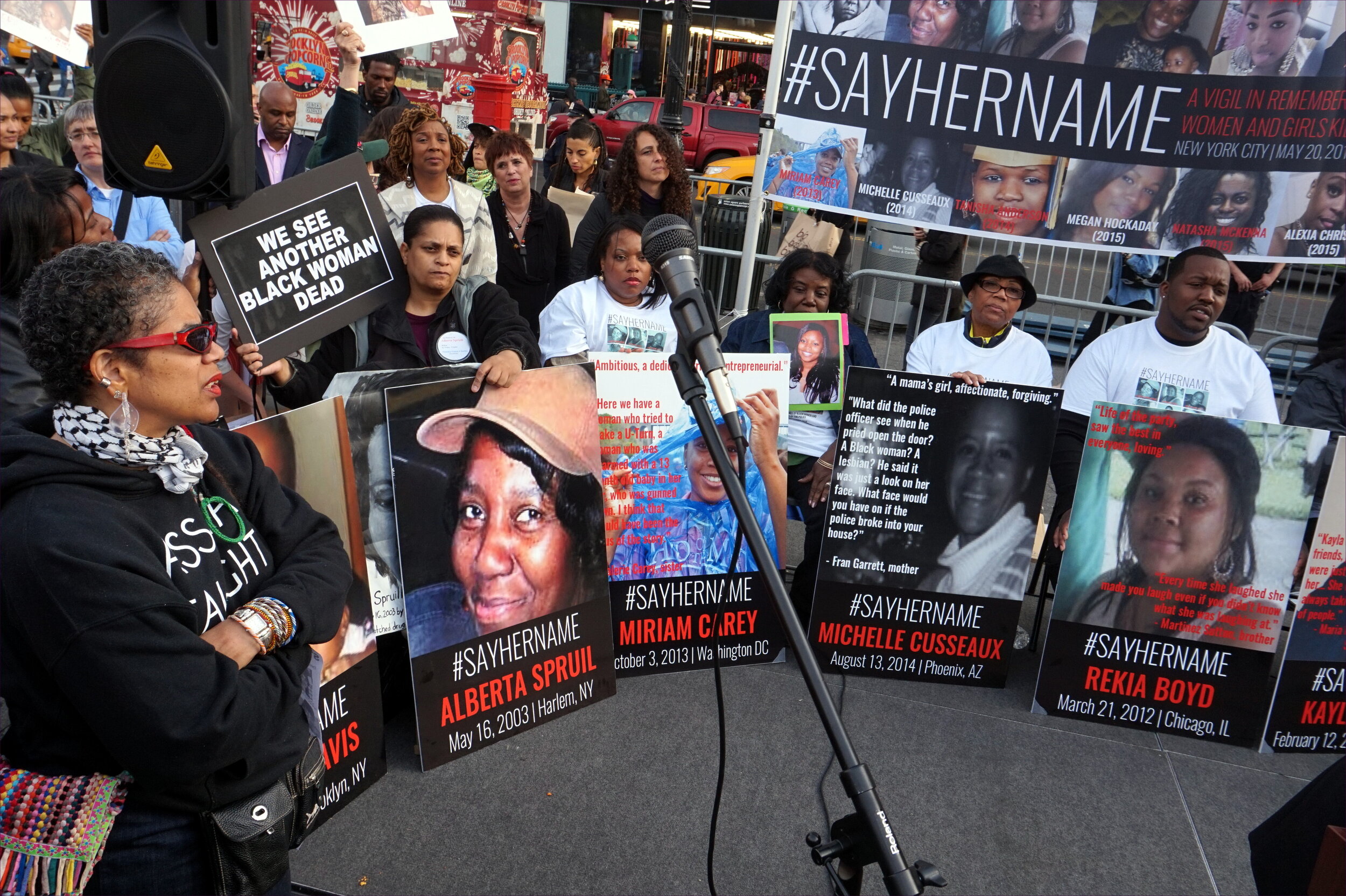

#SayHerName vigil in remembrance of Black women and girls killed by the police, 20 May 2015, New York, NY. Photo: #SayHerName

This particular Saturday church run is hard for me.

It’s an early morning like any other, when the sun beams in a mocking tone, not a cloud in sight, as if the rain lost its way to this muggy city. I haven’t spoken much about what happened to anyone. I write in my journal, as I often do, and the pastor is now watching me stare at the stained-glass windows, as he often does. I’m hoping that one of the colors above would make me feel something other than pain. The blues and the greens speak to each other often throughout the pattern. While I sit trying to figure out their conversation, the pastor approaches me.

“Well, there's a familiar face,” says Father Cousins. “I’m glad you’ve been coming more frequently lately. Is something wrong?”

I look at him as if he can hear all of my thoughts: Isn’t there always something wrong with someone who needs a prayer on more days than a Sunday?

I feel my eyebrows bunch up. I must look like a whimpering dog.

I’m not one for confiding in anyone but, I have no choice but to say something. Father Cousins does not usually pry, so I know I’m in a rare position. My lips stick, as if petrified to part, even for air. Unable to breathe, I smack them open enough to also mumble an answer.

“I’m not sure, Father.” I put my head down, trying not to cry. “I just want to hear God a bit more clearly than I have been, is all.” He doesn’t reply right away, which is all I need to hear from him. We don’t have a strong bond, though my mother tries to speak to Father Cousins almost every Sunday after service. He knows our family well because of it. But he doesn’t know much about me personally.

“You’ve picked the right place, then,” he says. “You know, the Lord can hear you from anywhere. But in His house, His voice is amplified.”

That’s what a pastor’s supposed to say.

I know God can hear me from anywhere—but did he hear my screams when I saw Alma’s lifeless body? Why, at that moment, didn’t he shield me from that image?

I look up at Father Cousins with a dead gaze. His smile is overbearing, makes me feel so guilty for not being able to give him one back. All I can tell him is, “Thank you, Father. I’ll see you tomorrow.”

Without waiting for his response, I stand up like a wooden figure and walk away. That house is just too much for me at that moment. God’s house. There are so many. So many churches for so many people like me, who’d rather not visit though invited daily.

One of the last things Alma told me was that she knew that she had God in her.

“Do you got God in ya?” she asked me, smiling hard at me as if joking, though I knew she wasn’t.

Alma didn't seem like the type to have ungodly friends. She was so motivated and brave, I would’ve been surprised if she had anyone in her friend circle tugging at her faith. A spirit so strong, it’s lifted above the others’. I didn’t get her personality at first, but as I watch a red-tailed hawk fly near Marcus Garvey Park now, I think I better understand who Alma was.

But the Ridgway's hawk is a different, particular kind of raptor. When I asked about the bird painted on her T-shirt, Alma said it’s native to the Dominican Republic. It doesn’t shy away from an open crowd, placing itself in the center. It loves to soar with like-minded birds and will sometimes trail the sky by itself. They are vocal and critically endangered.

If a caged bird stopped at nothing to peck its way out and still managed to sing without hate and resentment and dance jazz hands every day, you’d watch with your mouth open, too.

That was Alma.

That day, her wings were spread in the middle of a crowd, her natural habitat. The people she attracted automatically felt at home. And yet, she told me that she’d never truly been home. Alma was born in the States and traveled to DR every other year, but she longed for a place to call home home. Here in Harlem, she said faith was the closest she’s ever been to home. And I thought I knew my faith. Alma knew she wasn’t free and had to escape the cage somehow, but she was going to sing and dance in the meantime. She was loud, unapologetic, and wildly unafraid of danger.

“Of course I've got God in me,” I’d like to tell her about my own spirit one day, when I meet her at the gates of Heaven.

I just desperately need a new flight path to God.

Wishing Tree, c. 1937. Photo: Aaron Siskind

The legendary “Tree of Hope” of the Harlem Renaissance was once a tall elm that stood outside a theater at 132nd Street and 7th Avenue. A piece of the original trunk is preserved in the Apollo Theater on 125th Street between Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. and Frederick Douglass Boulevards.

I walk by my college on the way home from church every day.

Up the hill, by the St. Nicholas city park. Down the long cobblestone road. Past the 1-train subway station across the street from the New York Library, and then make a right. That journey from 145th Street to 110th Street is longer these days, of course. Still bustling with the same energy. Someone’s parents are blasting samba, and the oily, flaky smell of empanadas from a cart travels harmonically to the tune of the beat. The sky is eager to purple over, though the sun doesn’t quite meet the horizon. Not yet. Everyone’s smiling, laughing and telling stories about their day. I must be one of the few people who can’t look up the street for too long without seeing the scene over and over again. If you’d remove all the protesters between Alma and me and, in bird’s eye view, seen her get hit and rolled over, you wouldn’t forget the image, either.

I make it home with heavy feet as usual and attempt to sneak in the front door.

“You know you don’t have to creep in like a stranger, right?” my mother says.

She’s washing those same dishes she always washes, despite it only being her and me now—though I opt for more environmentally friendly paper plates with poorly designed floral patterns.

“Yeah,” I mumble, “but I wouldn’t want to disrupt you when you’re hard at work.”

“Ha, ha. Very funny,” she says, turning off the tap. “I know you think I do this all day, but I really don’t.”

“I didn’t say that, Momma.”

She puts down the last dish on the drying rack, takes off her bright-yellow rubber gloves, and turns to me. She is tired, like always. Her beautiful face, no stranger to the creases of worry, doubt, and fear. A gracefully aged tree.

“The cross can heal and hurt; it can be empowering and liberating but also enslaving and oppressive,” is one of my favorite Cone quotes. Maybe it’s because my mother reminds me so much of the tree that adorns the cover of Cone’s book, The Cross and the Lynching Tree.

I told Alma she would’ve liked my mother. They are both healers with the potential to cure everyone they encounter. Their lives bring everyone together, faster than a two-step jive even without music. Their branches carry leaves of green, prospering and energetic—only to brown over and fall away with the changing seasons, bringing back new ones indefinitely. These women are life, the air we breathe, the unworried lenders, always giving. Alma left her stump and Momma is willowing. Their annual growth rings elapse too quickly and are unable to nurture a healthy season.

But I’m still here in Harlem, perched on their branches, still believing in flight.

INSPIRATIONS

Barger, Lilian Calles. “The Strange Fruit of American Religion.” Society for US Intellectual History, 15 Aug. 2018.

Cone, James H. The Cross and the Lynching Tree. Orbis Books, 2019.

Contreras, Felix, et al. “The Afro-Latinx Experience Is Essential To Our International Reckoning On Race.” National Public Radio (NPR), 3 July 2020.

Davis, Tyler. “The Weight of His Words.” HTI Open Plaza, 1 February 2021.

Hughes, Langston. “Let America Be America Again.” Power to the People, Poets.org, Academy of American Poets.

“James H. Cone.” Enoch Pratt Free Library.

Jones, Victoria Emily. “Roundup: Rock Hall Inductions; James Cone; Lynching Memorial; ‘Christ in Alabama.’” Art & Theology, 8 May 2018.

Lebron, Chris. “Who First Showed Us That Black Lives Matter?” The New York Times, 5 Feb. 2018.

Oates, N’Kosi. “Religion in the Work of Langston Hughes.” AAIHS Black Perspectives, 16 June 2018.

“Religion & Violence: James Cone Interview.” Trinity Church Wall Street.

“Theologians and White Supremacy: An Interview with James H. Cone.” America Magazine, 28 Apr. 2018.