Phantoms of Fire

Sammie Seamon on growing up within the Apostolic Pentecostal tradition

And when the day of Pentecost arrives, the crowd of worshippers gathers together in one place.

The group of believers belong to each other completely, under one house, worshiping the same God, set alight with the same fire. At a sound of heaven, they are filled with the spirit of God, alive with the voices of strangers and those divine beings unseen. The spark of true belief envelopes those who were there and those who will follow.

Be with God with all of your heart and soul and strength, and you, too, will speak divine words, becoming a prophet for God as He addresses His people.

Old men in collared shirts skip, twirl, and dance down the aisle, their ages unrecognizable. Women run back and forth in the sanctuary, hollering as they go, the sound carrying over the large room. Many others raise their voices incoherently, perhaps in a language given at the Tower of Babel or just sound released from pure emotion.

As my ears adjust to the sound, I grip the wooden pew and lean forward.

Suddenly, a voice booms from the middle of the room. The space that roared in one moment shutters into silence at the sound of the voice rising above the others, wailing forward words no one in the world can understand. The voice explodes from a middle-aged woman whose three kids stare up at her, along with another thousand eyes.

When she stops speaking, another woman interprets the incomprehensible. Like many messengers before her, the first speaker often has her hands raised towards the high ceiling, above the sea of people. The translator that follows simply stands, hands at their sides, exclaiming what they believe to be the spoken word of God.

***

The foundation of the Pentecost is the Holy Ghost, as it is called: the phantom of fire that possesses the tongue. It must be received in the form of a new language for all believers to truly know if God has chosen them for eternity.

When this phantom is invoked on my behalf, I am nine years old, with my elbows on the deep-purple satin steps of the altar and my forehead to its surface. The hands of strangers press heavily on my back as waves of their murmurs pour over my head. They pray for God to pick me, their child, and wait for me to begin speaking in a language I don’t understand. I understand what they want but not how to do it, and as I pray and pray for the miracle to happen, I become overwhelmed by the growing crowd of strangers, the heaviness of hands on me, I don’t know where my mother is, and I want to go home… it’s getting late, and the church is emptying. As strangers lift my small elbows to the sky, I begin to cry– not out of love for God but because I am desperate.

There is another girl to my left, probably six or seven years old. Strangers’ hands are pressed upon her back, and her face is close to the soft steps of the altar. She is sobbing loudly. She dips her head to the floor, licks her palms and quickly rubs them on her cheeks, raising her shining face to the crowd.

Rooted in Church

My father refused to attend my mother’s church. He thinks Pentecostals are too loud, too wild. Elderly people aren’t supposed to run down aisles. He grew up in a quiet Baptist church in Montgomery, Alabama in the 50s and 60s, with segregated neighborhoods and churches packed with all-white congregations in their Sunday best.

We eventually found that church in Austin, where I grew up. The white-steepled Baptist church stands on a hill. Primarily white families politely line the pews, shushing their children and singing while standing, hands by their sides or gripping the pews, never clapping. The pastor, a scholar of the Bible, pours over the given text in advance of Sunday, taking notes and printing out paragraphs to be read from with precision. We begin Sunday at this church and end it at the Pentecostal one, sleepy quiet to a wildness.

Frankly, I think Baptists are afraid of doing what Pentecostals dare to—or maybe my father’s people are afraid of God. To them, God is too distant to physically throw oneself at His feet. Pentecostals do this amidst collective hallelujahs, stripping away the civility of the secular world for something greater.

***

My abuela was baptized in the 1980s, when a preacher came with La Santa Biblia to their small village of Tepoxtepec in the southern Mexican state of Guerrero, where my mother grew up. He was a traveling man who wished to change the lives of people who were willing to listen—or at least willing to cover their bases when it came to making it into a better next life. There was no church in Tepox at the time, only families reading the Bible and worshiping Catholic saints in their own homes. Years later, another pious man named Juan Río drove to Tepox from his church in Iguala. Río befriended Uncle Miguel and my great-grandparents, and eventually began preaching regularly in their modest home, as my mother and others brought in chairs and listened.

Abuela would not enter a church; she thought she lived in sin. She once dated a man who was married, when she and my mother lived in Cuernavaca, a city in Morelos. They moved there from Tepox after my grandfather disappeared in the US, where he went to find work; he stopped sending money, and they needed an income. When they finally arrived via coyote to Texas, where the rest of the family had already settled, Uncle Miguel and the rest of my mother’s uncles encouraged Abuela to attend their church, Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Hispana. She walked out of that church for the first time both hurt and convicted, and felt that the preacher spoke into her life. After some time, the guilt healed over and she fell in love with the church. She became one of around 2,000 Spanish-speaking Hispanic attendees living within the primarily-Mexican community in Houston. The church, preached in Spanish, became her family and a source of help in an unwelcoming city, as it has for so many of those without English and little other means of support and community.

When I am nine years old and my sister is seven, my mother wants us to audition for the Christmas play, held every year. I get the lead role, Hope, and my sister gets a side part. The mothers run to the casting lady, demanding that their children be given the parts instead. Because we are different. My sister and I are backsliders: we go to public school, and rumors go around that our mother let us wear pants. There are, after all, rules for girls, and my sister and I do not follow them outside of the church. We are only to wear skirts below the knee and shirts with sleeves to the elbows. We are to never cut our hair or be outwardly luxurious with visible makeup and jewelry. Women are to have long hair that goes down to the knees or ankles, the split ends parting into strings. Women with thick hair wear it like a sheet as it pulls the head backwards with surprising weight. It seems that conservative men want their wives to dress in public: as bodies behind a curtain.

We, though children, are imposters and don’t deserve to be onstage. But my sister and I go to rehearsal every Wednesday and Sunday night, and my mother makes us go over our lines daily. At show time, as the children come forward, the pastors step aside for the night, so we need to present something worth their time; the auditions are thus crucial to make sure we aren’t an embarrassment. Under such pressure, and encircled by stern women dressed in black and white formal wear, the lines come out of my mouth louder than I expect.

The glaring adults watch from the pews with crossed arms, and even their children seem afraid to talk to us.

My mother and my family were not Pentecostal before attending La Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Hispana and never had these rules, though they had attended churches with similar ideologies; while my mother and older relatives did adopt these customs in the US, my sister and I and our cousins were never made to. I wore skirts every Sunday and had my first haircut at 14, but in comparison to the other girls in the church, I was living free.

The Soul-Winner

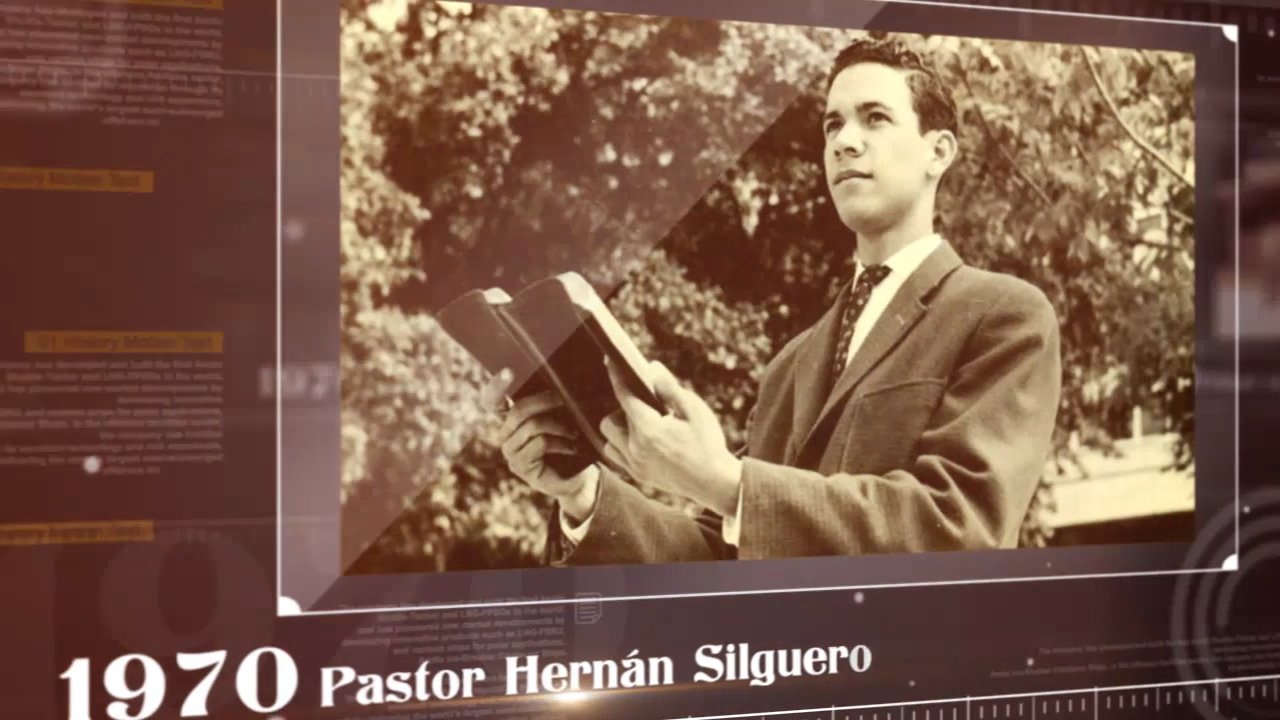

Hernán Silguero rode the train from Colombia with only his sister, settling in Houston, Texas after making it into the U.S. Still teenagers with little money, they slept in a car and lived off of the occasional goodness of those in the neighborhood. He was hated by others, especially when, in exchange for food or company, he brought his Bible to the doorsteps of his neighbors to preach, much to the annoyance of those long-disenchanted with religiosity in those dark suburbs.

One of those who hated him, a middle-aged woman, invited him into her home on the pretense of wanting a discussion. After serving him coffee spiked with a lethal amount of poison, she sat and waited for him to die. A healthy young man, he remained upright, reading from his Bible. It was then that she suddenly believed in his words, in the God who had protected the boy from death.

There in her living room, she helped him start a church, inviting anyone who wanted to stop by and hear what the boy had to say. The church grew until bursting, and they had to find another space. As Hernán grew older, the church exploded into the thousands, and those who arrived in the asphalt city without English gathered in prayer, mumbling under humble breath and shouting into the sky.

They called him el ganador de almas, the soul-winner.

All of the money donated to La Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Hispana went to the other churches that were trying to start in the area. Even as his church soared into the thousands, Hernán continued to drive the same old car and neglected to gain material possessions. He helped my tío Miguel purchase his house, urging, “Hermano, buy this house, it is close to the church.” Hernán himself inspected the house and the concrete courtyard in the interior of the property, where tío Miguel and my cousins live to this day, where I had my third birthday party. Juan Río, still the pastor of the church in Iguala, even comes to Houston to preach in Hernán’s church during Pentecostal conferences. Though the church in Iguala lacks denomination, Juan and Hernán share the same spirit, in a space built for worship, community and survival.

Image of Rev. Hernán Silguero from iCentral 45 Aniversario (2017), a documentary about the history of La Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Hispana

Taking on the Real World

It is hard for an outsider to understand what a self-contained community is like.

In the Pentecostal church I grew up in, and to a lesser extent, the Baptist church, the families and children intermingle in the most personal manner. The men are my brothers, the women are my sisters, and I must call them as such, even if they are decades older: Sister Kinney, Brother Shaw, Brother Bernard, Sister Dumas. Ironically, the teenagers do not address each other in this manner though more similar in age, and are the closest friends they each have at all.

Most of the parents engage in their own education; they parent each others’ children, and children are punished as a collective. We are told not to closely befriend kids outside of the church; they will lead you astray from the life your parents have so carefully built up. Once the generations of youth grew old enough, they began to date and marry each other in quick succession, usually soon after high school graduation. Young girls in long dresses marry pubescent boys who believe a girl from the church is their entitlement. The youth needed to be contained and paired. Thus, most are homeschooled or, if it can be afforded, attend Christian private schools.

To my knowledge, my sister and I were the only ones in public school. We were in science classes, we wrote critically and creatively, we made friends with different viewpoints, I had crushes on multiple boys and girls.

And then I decided to attend a liberal arts school in the northeast. In both Mexican and Pentecostal culture, children who leave for college or with a spouse far away are considered to be deserting their parents. Of the Pentecostal girls I know who went to college, all went to rural Christian colleges in Texas, within a few hours’ radius. My cousins are made to go to the University of Houston, the same city they grew up in, because Tío Miguel won’t allow them to apply outside of the city. When I decide to go to Williams College, Abuela is quietly angry with me and says so to my mother.

I flew two thousand miles away, to somewhere dark and unfamiliar in every sense.

***

When my sister comes out as bisexual, my mother seems at first afraid, then indignant, then lapses into a passive acceptance. I am sure that homosexuality did not enter her attention throughout the forty-odd years that preceded this event; it is different but not utterly opposed to what she is willing to accept.

What she was afraid of, when it came to my sister and I, was the church. In both Baptist and Pentecostal churches, a single misbelief will send the whole tower crumbling down. They would question why my parents would allow us to live in this way. What they would not denounce, the church will, and it would end in the blacklisting of our family.

Thus, we cannot be genuine, and my sister and I have long ceased to care. They may believe themselves to be family, but will never know many things about us: we are politically active and opinionated, too unfeminine for their standards, have been in relationships without a promise to marry, and are liberally educated. They would be uncomfortable with the things that we know, our learned confidence, and how prepared we are to take on the real world in a way the church never intended us to be.

***

This summer, when I visit my mother’s home in Tepoxtepec, I will not be able to wear most of my clothes. I will not be able to put on a t-shirt and shorts in the equatorial heat and run around the village, exploring its streets and borders for myself, alone in movement. Even in motion, I may not be safe—the small, poor rural village has been plagued by drug cartels stationed in the surrounding mountains. This aside, machista culture is prevalent, and it is better to blend in.

My mother changed the way she dressed because of the church, to fit in, but also because it became what is comfortable. She now avoids exterior signs of luxury: painting her nails, wearing jewelry, putting earrings in the piercings done when she was born. But she truly does not believe that appearance reflects the soul, and even now tries to extend this same forgiveness to herself. She carried long, heavy hair for most of my life, until she cut it recently, with some fearful excitement. When I was little, I would stand behind her as she sat and lift the mass of hair, marveling at how I could barely hold it.

***

When my mother arrives in Austin after marrying my father, she hears that David Bernard has a church in the city. La Iglesia Pentecostal Unida Hispana carries books in their library by Pastor Bernard, a well-known, white, wrinkled theologian and a respected figurehead of southern Pentecostalism. When my mother arrived in Austin after marrying my father, she heard that Bernard had a church in the city. I am enrolled in the New Life Austin pre-K Sunday school that I soon begin calling Happy Chappy.

There, I make my first friends. Most of those men and women are still at the church. Some are married to each other, some have kids. Some are at Christian colleges, many of the men at seminary, wanting to start their own churches. I become a part of their group, going to church even three times a week as a child, and the other mothers look at me with the same affection as if I am their own.

As we grow older, these friends start to sit, separated by gender, in the front two sections of the church during service. The women twirl their long flowing skirts, singing in soprano, and the men in suits stand, one hand in pocket, one hand raised towards God. Wearing a t-shirt and one of the four skirts long enough that I own, I stand in the back with my mom and my sister—later, with my baby brother, too—and watch the young adults I have known since childhood. They do not know me anymore and are unaware that my family is still here, in the back, over a decade later.

In this space, I am forgotten, but I at least had the choice to go.

***

The assistant pastor raises one hand, the other hand holding a wireless microphone as he paces across the stage.

“Have the doctors done you no good? Have they told you there’s no hope? Well, I’m here to tell you that there is hope in the name of our Lord Christ Jesus. All who are ailing, step forward to receive your healing blessings from God.”

Lines of the old, frail, sickly of all ages who need help—frankly, a miracle—shuffle towards the altar. Younger people also line up for God to heal them of porn addiction, or love of the world, or sexual attraction to someone other than their spouse. When each of the afflicted reaches the front, the preacher dips his fingers in a gold-tinted oil and presses it on the forehead.

Once most have returned to their seat, a few people often make their way to the front to whisper into the preacher’s ear. He then takes the microphone to announce that one old woman has been cured of her chronic back pain, another of a chest infection. The space erupts in rejoicing for the ones God has chosen to cure on the basis of their devotion. A train of people lines up around the perimeter of the large sanctuary, hands on the backs of each others’ shoulders, and dance and shout as they circle around, the room filled with the sounding of hallelujahs. The roar fades as my father signals for us to leave, and the double doors close softly behind us.