On Music, Justice, and Hope

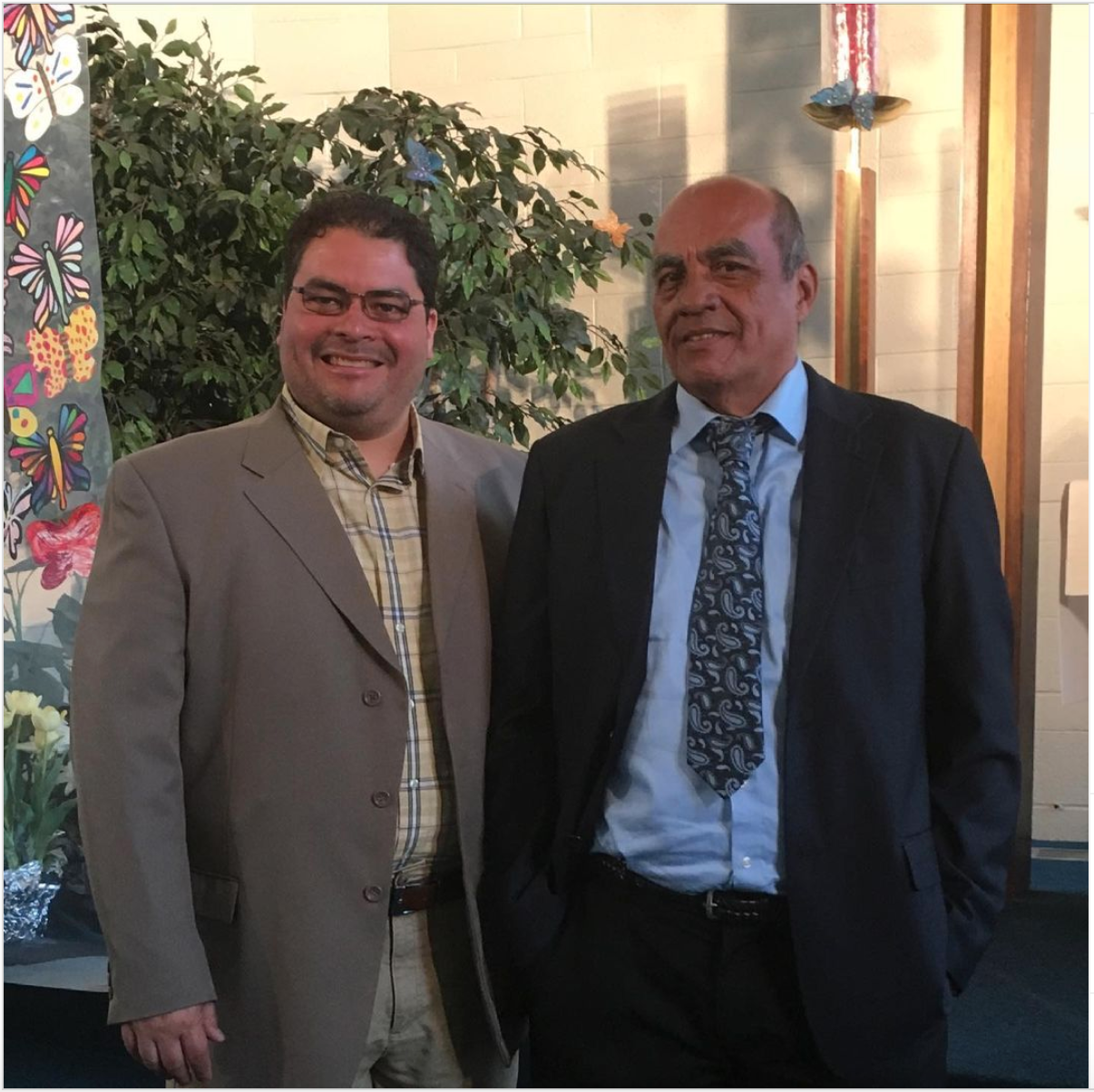

Dr. Leopoldo A. Sánchez M. serenades Instituto Nacional de Panamá Class of 1966 alumni: his father Carlos Sánchez, musical artists Basilio Fergus and Rubén Blades

Sphinxes symbolizing wisdom and genius guard the entrance of the Instituto Nacional de Panamá, a cultural heritage monument. Panamá City, Panamá, 2016. Photo: KarlaOhhh

Aguiluchos

My father Carlos Sánchez recently sent me a digital picture of his handsome high school self.

He is a graduate of the historic Instituto Nacional de Panamá, founded in 1907 as Panamá City’s first public high school. Guarded at the entrance by two bronze, winged, woman-headed sphinxes and affectionately known as “El Nido de Águilas” (the eagles’ nest), the Instituto is known for forming many of the country’s great minds, ranging from politicians to educators to artists.

Instituto students have a strong sense of national identity and social consciousness. During the years of U.S. military presence in the Canal Zone, an area of the country over which the United States held jurisdictional authority from 1903 to 1979, Instituto students participated in various protests demanding Panamanian sovereignty over the Zone. On January 9, 1964, a group of Aguiluchos (Eaglets) and others walked to the Zone’s Balboa High School to demand that the 1963 Treaty Chiari-Kennedy, which allowed for the flag of Panama to be raised in some areas of the Zone, be honored. The unsuccessful attempt ended up with the flag being ripped amid riots and in civilian deaths—a day of national mourning that Panamanians commemorate as El Día de los Mártires (Martyrs’ Day).

“Instituto students participated in various protests demanding Panamanian sovereignty over the [Canal] Zone.”

Image: LIFE Magazine (24 January 1964) covered the events on Día de los Mártires. Source: University of Florida George A. Smathers Libraries.

Among Aguiluchos were members of my father’s graduating class of 1966, including Basilio Fergus (1949–2009) and Rubén Blades (born 1948), two artists who became popular singer-songwriters with a penchant for social critique. Using their music as a medium for denouncing injustices and painting hopeful pictures of a more just world, they represent the Aguilucho spirit.

Basilio Fergus

Carlos Sánchez

Rubén Blades

Images courtesy of Leopoldo A. Sánchez M. Source: Anuario del Instituto Nacional de Panamá, 1966

Basilio Fergus

Of the two artists, Basilio Fergus is the least known to U.S. audiences.

Contemporary salsa fans may know him indirectly through a 1994 popular adaptation of his ballad “Vivir lo nuestro” (1986), sung by Nuyorican artists Marc Anthony and La India. The song depicts an interracial couple that dreams of a world in which there will be no more lamenting over divisions based on race and color (“Soñar, soñar despiertos en un mundo sin razas, sin colores, sin lamentos”), a universe in which black and white will build a future together (“En un universo negro como el ébano más puro voy a construir de blanco nuestro amor para el futuro”). Basilio wrote from his own experience as a black man married to a white woman, living at a time when racism and colorism were not uncommon in the Spanish-language world and music industry.

In his earlier “Cisne cuello negro” (1977), Basilio paints a scene from nature in which black and white swans share love, hurt, happiness, and sadness, as they swim through life in a lake that is “neither black nor white” but rather “an immense lake filled with mud” (“No hay un lago negro y un lago blanco, y un lago blanco. Hay un lago inmenso lleno de fango, lleno de fango”). Basilio’s images neither romanticize racial relations nor ignore racial tensions. Like our complaints, times of quiet, cries, and songs, so also may the great lakes and vast fields not be black or white but “muddy” places that are hard to navigate, where we can hurt or kiss each other. Yet he also calls for people to sow a field, to care for a world that is bigger than we dare to imagine (“hay un campo inmenso para sembrarlo…hay un mundo inmenso que hay que cuidarlo”).

Rubén Blades

The events of January 9, 1964 influenced Rubén Blades’ outlook on the world.

It moved him from an early interest in American Rock to explore more deeply the sounds of Latin America, with a special focus on the Afro-Cuban roots of his mother’s native Cuba. While a student at the University of Panamá, Blades sang in Panamanian salsa bands (known as “conjuntos”) and, in 1965, wrote the anthem dedicated to the martyrs “9 de enero,” his first serious song, later recorded and performed by Panamanian salsa group Bush y sus Magníficos in 1967.

Blades has written numerous songs that speak to the theme of hope amid suffering, many of them with a spiritual sensibility that bears an affinity with biblical themes.

In one of my favorite pieces, “La canción del final del mundo” (1985), Blades juxtaposes an upbeat salsa rhythm with the sober theme of the end of the world. In the early ’80s, Cold War tensions had escalated with Soviet deployment of ballistic missiles targeting Western Europe and U.S. deployment of missiles in Western Europe targeting the Soviet Union, as well as with NATO’s nuclear war simulation exercises. It is in this context that Blades writes about the power and threat of the bomb. Yet he does it with levity, noting that “humor is essential in the face of pain” (“Ante el dolor el buen humor es esencial”).

To describe the end, Blades uses the analogy of a night club, of life on earth being taken for granted, like a good and cheap show–but now the time has come to pay the tab for our actions (“y ahora nos llegó la cuenta y tenemos que pagar”). Time to get that last drink without complaints, and ask your partner for one last dance to receive the end of the world. Improvising, the singer calls people to live rightly in the world before it is too late and the day of reckoning arrives. Salsa dancing is a form of resilient fiesta in the face of the end and, paradoxically, a call for action before the end comes: “There is still time to save this earth of mine, so let’s do what needs to be done” (“A tiempo estamos todavía de salvar la tierra mía, vamo’ a hace’ lo que hay que hace’”).

Drawing from biblical depictions of God’s deliverance of his suffering people, and their own experience of resilient fiesta amid “la lucha,” U.S. Hispanic theologians often reflect on what it means to live everyday life (“lo cotidiano”) with hopeful faith and love amid injustice and evil. When seen and deepened through interaction with the biblical world, Basilio Fegus and Rubén Blades remind us to sow, nurture, and dance in this world through practices of lament, solidarity, and justice, prophetic calls to repentance from sin, and the proclamation of salvation.

Carlos Sánchez

Growing up, these were the values I learned from one of their classmates: my own father, Carlos Sánchez.

After completing studies in chemical engineering in Chile, where he met my mom Conzuelo and I was born, we returned to Panama. But rather than pursuing a job in his field, my father began a career in public service, working in leading administrative roles for the Ministerio de Trabajo [Ministry of Labor] in the area of labor-industry relations and for the Caja de Seguro Social [Social Security Administration] in occupational health and safety. He continued to advocate and labor for the wellbeing of workers during his tenure in the Panama Canal Commission, where he facilitated health and safety education and compliance for contractors. On a visit to Panama from college, I attended one of his talks to workers–I was blown away. Rather than speaking about the need for safety in terms of productivity or economic liability, my father, inspired by his Christian faith and the Aguilucho spirit of social responsibility, spoke about the moral imperative of safety and the ethical obligation to a safe working environment as a matter of justice, for the sake of one’s marriage, family, and human flourishing.

A lifetime of vocation in administration, field work, and teaching on behalf of workers defined Papá’s’s lucha and legado (legacy). In his own way, he was an organic intellectual who embodied for me the Aguilucho spirit of a strong work ethic, solidarity, and disciplined study in service to his people. It is quite fitting that Papá completed his service under the Commission’s new name, Autoridad del Canal de Panamá (Panama Canal Authority), a title change that signaled the full transfer of the Canal to Panama. Carlos Sánchez did not only lament the events of 9 de enero as a young student; in God’s good time, he was also blessed to see the Panamanian flag soar everywhere in the Canal and to contribute to his own country’s peaceful transition to a Canal fully operated by a healthy, safe, and flourishing Panamanian workforce.

“Feliz día, Papá” (Instagram post @salsasanchez, 20 June 2021)

Together, these three Aguiluchos of the Class of ’66–Carlos Sánchez, Basilio Fergus, and Rubén Blades–invite us to live today in accordance with the hope of a new world in which God dwells with his creatures in peace and justice.

¡Que viva Panamá!