Hermenéutica elefantina

Dr. Kay Higuera Smith on listening with humility and grace

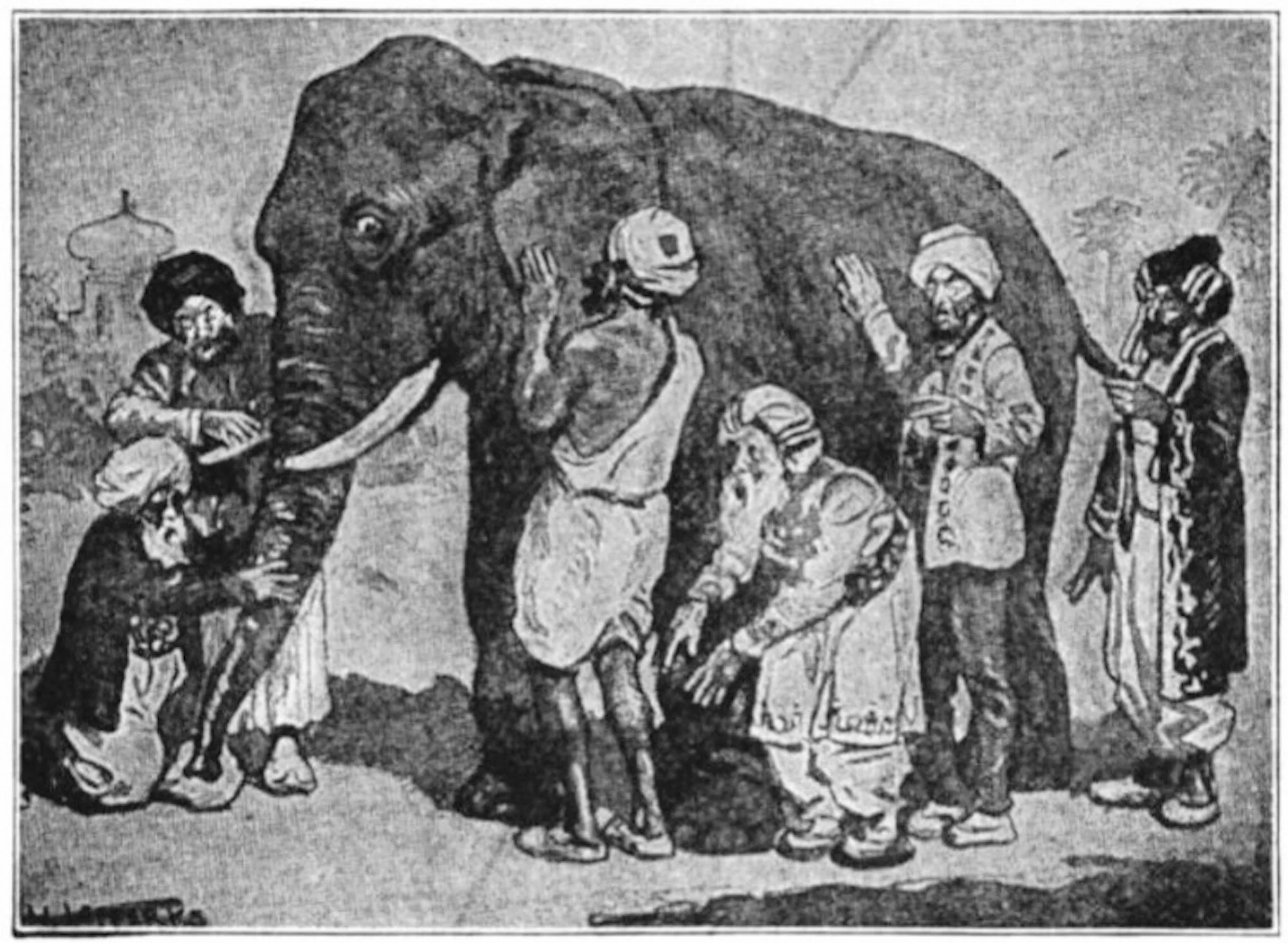

The ukiyo-e print "Blind monks examining an elephant" (1888) by Hanabusa Itchō illustrates the Buddhist parable in which each man reaches a different conclusion based on which part of the elephant he has examined. Source: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

You’re sitting in a tea shop in Eagle Rock, just north of Los Angeles.

The aroma of teas wafts through the shop, some sharp and biting, some soft and mellow.

You’re looking at the people around you. One man is in flip-flops with craggy and cracked feet, legs crossed casually as he engages in rapid conversation with an older man in a business suit and Italian shoes shined to a high gloss. You pick up bits and pieces of the conversation—about 75%. The men are discussing the morning news. One supports the current president; the other opposes. One interprets the political changes one way; the other interprets them another way.

¿Qué está pasando? Why are they interpreting the same events in completely different ways?

Consider the mental processes involved when you first meet a person. In a fraction of a second, your mental computer takes in that person’s dress, hair style, shoes, clothes, accessories, tattoos, age, gender—whatever input is available. Your computer brain stores that information in a well-stocked hard drive. Then, in the next fraction of a second, your brain categorizes and maps the person according to the taxonomies—the structured, hierarchical lists and categories--that you have collected and collated over your lifetime.

The program is so natural, you don’t even know it’s running…at a tea shop in Eagle Rock as you watch two men argue and consider each of their arguments. It is likely that their different social experiences, or social locations, have shaped how they experience the world, how they make meaning of the same events.

Illustration for the "Blind men and an elephant" parable from World Stories for Children by Sophie Woods (Ainsworth & Co., 1916)

Elefante in the church

I’m a californiana and an academic in the field of religion. My familia’s collective memory has been passed down generation by generation at the family gatherings, at the feet of mi abuelo y abuela. But I live in a largely Anglo-European world, surrounded by people abuela used to call “gringos.” I’ve adjusted to that world. My own father is a gringo, and he always encouraged me to develop in any way I wanted. As I encountered the larger world, though, I found that neither the Anglo world nor the world of religious scholarship was interested in the Latina part of myself.

This self is just as important a lens through which I can make sense of the world. However, my Latina experience is rare in the field of religion. I construct meaning based on my experiences and my urgent questions — the way we all access everything else in the world.

What, then, am I doing in a world that is asking questions in which I’m not interested? Moreover, how many people in our Latinx churches are asking questions fed to them by the dominant Anglo culture?

¡Qué dilema!

A solution to this dilemma: Value our unique experiences and put them in the foreground. These experiences include geography, gender, class, sexuality, social memory, age, generation, the historical events that have shaped us—I could go on and on. We must also insist that our Anglo-European friends likewise admit to their own frames of reference and stop masking them as “defaults” to cloak their power claims.

All too often, we hear church sermons in our Latinx churches that address urgent questions that shape or preoccupy the dominant Anglo culture and barely address our own social location. All too often, the pulpit completely ignores our rich social locations as multiethnic, multiracial mujeres—women who hail from Los Angeles and Buenos Aires to Guatemala City and Santo Domingo.

Hermenéutica latinx

Such questions about personal meaning making become even more urgent when we engage Scripture. After all, for Jews and Christians, the Bible—Torah and Tanakh for Jews, Old and New Testaments for Christians—is authoritative for shaping meaning. This is why, in my own academic research, I have gravitated to hermeneutics, specifically, Latinx hermeneutics or decolonizing hermeneutics.

”Hermeneutics” is a Greek term that simply means “interpretation.” Interpretation is an art that we practice in formal and informal ways. It is as much the art of interpreting a play, piece of art, or novela as it is a vehicle for intellectual analysis.

Therefore, as a religious scholar whose social location includes a Latina experience, my hermeneutics pose urgent questions, such as:

What are the social/ historical/ geographical/ linguistic factors that produce meaning in la Biblia? How does one factor shape the other(s)?

How can meanings be expanded to make room for those whose voices traditionally have not been heard, for perspectivas that have been silenced for lack of social, economic, or political power?

In what ways might the social location of the dominant culture in the U.S. cause meanings to emerge that do not take into account the experience of Latinx populations?