Far and Near

Rev. Dr. Harold J. Recinos presents excerpts from his latest collection of poetry The Looking Glass

The Library (1960) by Jacob Lawrence. Tempera on fiberboard, 24 x 29 7⁄8 in. “Jacob Lawrence researched many of his paintings of African American events by reading history books and novels…[The] standing figure in the front looking at African art may represent the artist as a young man, delving deeper into his heritage.” Image and caption source: Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of S.C. Johnson & Son, Inc., 1969.47.24

HTI Open Plaza kicks off National Poetry Month with ten poems by Rev. Dr. Harold J. Recinos from his latest collection The Looking Glass: Far and Near (2023), excerpts of which are used here by permission of Wipf and Stock Publishers. The poems in this feature are paired with works by Charles Demuth and by Jacob Lawrence—artists who collaborated with Rev. Dr. Recinos’ favorite poets, William Carlos Williams and Langston Hughes, respectively.

POET’S NOTE

Many years ago, I was moved by the identities of two poets whose works about life on the hyphen is familiar cultural terrain to me. One of these beloved poets is William Carlos Williams, a pediatrician, an author and a friend of Ezra Pound. Although Williams wrote in English, his first language was Spanish, and he had a plural cultural background. His mother was of French extraction and born in Puerto Rico; his father was born in England and raised in the Dominican Republic. I discovered Williams in the seventh grade, along with another well-traveled poet who has influenced me a great deal: Langston Hughes. My own poems issue forth from a life on the hyphen that began in the South Bronx. I pray that my work inspires readers to think differently about what counts for knowledge and to come open to the unexpected rewards offered by the barrio.

—Rev. Dr. Harold J. Recinos

Simplicity

I recall a time when life was

simple, knotless, uncomplicated

and occupied by hopscotch, round

up tag, stick ball on the street

and subway rides to Manhattan

for the hell of it. the first day

of the public-school week never

failed to find its way to Friday

when most of the block kids found

themselves in Margarita’s apartment

for a little night of salsa

and floating dreams.

where did that simplicity

come from, perhaps the candles left

burning by mothers

in the local Catholic

church, charms from the Ponce Botánica

worn around our skinny necks, stories

from Spanish lands holding us by the

hand to prevent shattering or the long

conversations with the old men of the

block who made us laugh. I recall days

when we were free of the fallacies of

modernity, the distortions of detestable

politics, nights were spent on the roof

top, looking at the moon exhaling silvery

light and feelings of consolation were

abundant.

The Visitors (1959) by Jacob Lawrence, many of whose works are about the lives of ordinary Americans. Tempera on gessoed panel. Source: Dallas Museum of Art, General Acquisitions Fund

Latino at Seminary

in the seminary rotunda behind

a desk, to receive visitors entering

the hall from windy Broadway, they

come in with looks on their faces

of finding strength to believe in the

latest sediment of divinity in the

freshest theology taught. a little

ray of sunlight creaks into the space

while the sublime face of the janitor

from Guatemala smiles and shows a

gold tooth he got one migrant season

of a more youthful year. all day long

people eager to quench a thirst for

meaning enter the school believing

they will flourish in the sight of so

many fashionable religious scholars

and no one pauses to recall that the

building janitors who came from a

place pommeled by wars paid for by

citizens’ taxes too are made from the

dust of the earth. the chapel adorned

with belief that does not name days of

terror or believes the cross is a lynching

tree gathers visitors in time for praise,

while René makes his way to trash cans

in the Quadrangle to empty them.

The Migration Series, Panel No. 49: They Found Discrimination In The North. It Was A Different Kind (1940-41) by Jacob Lawrence. Casein tempera on hardboard; 18 x 12 in. Acquired 1942; © 2022 The Jacob and Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence Foundation, Seattle / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Source: The Phillips Collection

The Riddle

I was called to Washington Square

Park to read to a friend who went

blind in late life from the book by

Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Love in

a Time of Cholera. she loved this

story about romance that unfolded

over decades, with talk of aging, the

scent of bitter almonds, the fate of

unrequited love, and the dream held

by two of winning each other back.

the love story was for her a great

companion for conversations about

the beauty of crescent moons, the

chances young lovers strolling in

the park had to find happiness, and

the sound of laughter. I can tell you

she wore blindness like a magnificent

pair of pearl earrings, roamed the park

without mourning light, and listened to

me read her favorite author. now and then,

I would look at her sightless brown eyes,

leaning into her answer to the riddle of

love in a time of illness.

Lula And Alva Schön (1918) by Charles Demuth. Watercolor and graphite on wove paper; 8 x 13 in. Source: The Barnes Foundation

Fruit And Flower (ca. 1925) by Charles Demuth. Watercolor and pencil on paper; 12 x 18 in. Source: Christie’s

The Confirmation

I was looking at the fruit

dangling in the color green

from a mango tree and saw

parakeets nesting on their

secret spot waiting perhaps

for a sky full of stars. we

spent the afternoon with all

the ghosts who shouted on

the streets and went to war

to protest suffering, the elders

who had seen too much, the

peasants with permanently

blistered hands, the widows

and children standing tall in

divine light. we gathered at

the edges of the city to wait

for the patient stories from

the familiar margins, curse

evil at its core wherever it

takes possession of human

bodies and to revel beside the

mango tree with witnesses

who rehearsed with accurate

memories the messages that

give us life, even while tears

try their best to hold up the

messy world.

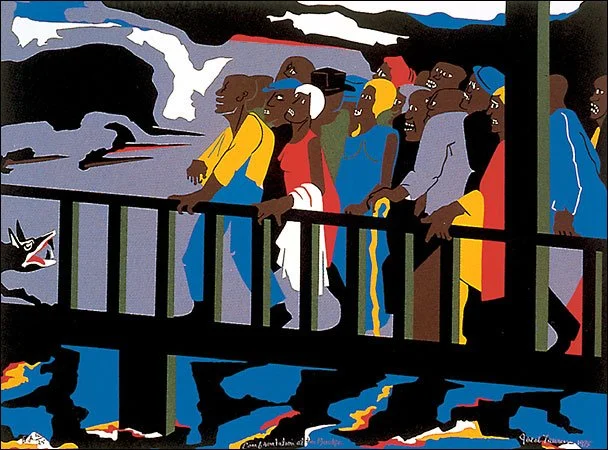

Confrontation at the Bridge from the series Not Songs of Loyalty Alone: The Struggle for Personal Freedom (1975) by Jacob Lawrence. Screenprint; 49.5 x 66 cm. Commissioned in honor of the United States' bicentennial in 1976, the work depicts a 1965 march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, AL by unarmed protesters objecting to the denial of African Americans' right to vote. Two days later, Martin Luther King Jr. led 25,000 marchers to Montgomery. ©Jacob Lawrence © Fair Use. Source: WikiArt

The Small City

after the little ones’ flesh

turns toward the dust, what is

left of them, will heavenly

gates open for them, and will

Angelic voices come to earth

to offer comfort to the families

whose children were mowed down

by bullets from a demon’s rifle that

obliterated every innocent dream.

yes, these beautiful lives mattered,

they had real magic in this divided

world, laughter for the sweet hours

after school and fresh sentences with

words often uttered in Spanglish that

carried mothers into the quiet hours

of night. yes, they were loved by people

striving for a better life and who have been

left with loud wailing in a near border town

of the land of the free and brave that

will hardly think twice about them. yes,

night in the small city will never end for

those exiled from light.

The Bible

before reading your

reverse standard Bible

that tells you another

story of a God who puts

out the lights, I want to

remind you the dead

like feathers are carried

to the places your faith

ignores. you dear servants

who read false words and

plead ignorance of the cries

on this noisy earth should

know the God you never

find in the book you prize

remembers every name

you despise. in the beautiful

world sustained by approving

love and unsteady worldly

kindness, God dropped in to

give us the light you never

held, fool! remember this

when you have your next

confused Bible-reading hour

to make foul interpretations

that never disclose the guiding

star of Bethlehem.

Incense of a New Church (1921) by Charles Demuth. Oil on canvas. Source: WikiArt

When I Think of Them

they heard the frightened voices

of children on 911 calls, like the

kids some of them would go home

to hug, and they let the minutes tick

away, with their special smell of the

burning of hell. they waited longer

than all the shots fired, dressed in

fresh uniforms with shiny badges,

ready to punish devastated parents

in the name of a police code too

dark for the innocent inside of the

school building to survive. we are

left thinking about all the loss, the

classrooms where blood was spilled,

with bodies beyond recognition that

will remain ripe with decay longer

than life itself. we have counted the

tiny broken bodies, the spots of God

left in an elementary-school prayer

cannot make whole. we rage at the

end of life for those with too little

experience to measure and the coffins

receiving them. at each graveside, we

stare at the sheltering earth that weeps

about the gun violence moving across

her sacred body.

Childhood Sketchbook Pages (n.d.) by Charles Demuth. Opaque paint on paper; 8 1/2 x 10 3/4 in. Source: Gift of Salander-O’Reilly Gallery, Demuth Museum Collection

Meditation

they asked him once in

the barrio how his life is

joined to history at the edges

of the city and the eyes on the

block no longer able to hold

tears. they held his calloused

hands in church to pray, his

tongue did not move, and his

thoughts were occupied by

the impossibility of salvation.

they wanted to know what it

felt like to hold a teen boy who

walked all night to reach him

to die in his arms. he said time

had become wordless sadness

and, like hoarse water, swallowed

under a frightening sky. I always

run into him sitting on the stoop

waiting for something, looking up

and down the street, sometimes even

up at heaven, searching, I think, for

signs of chariots swinging low.

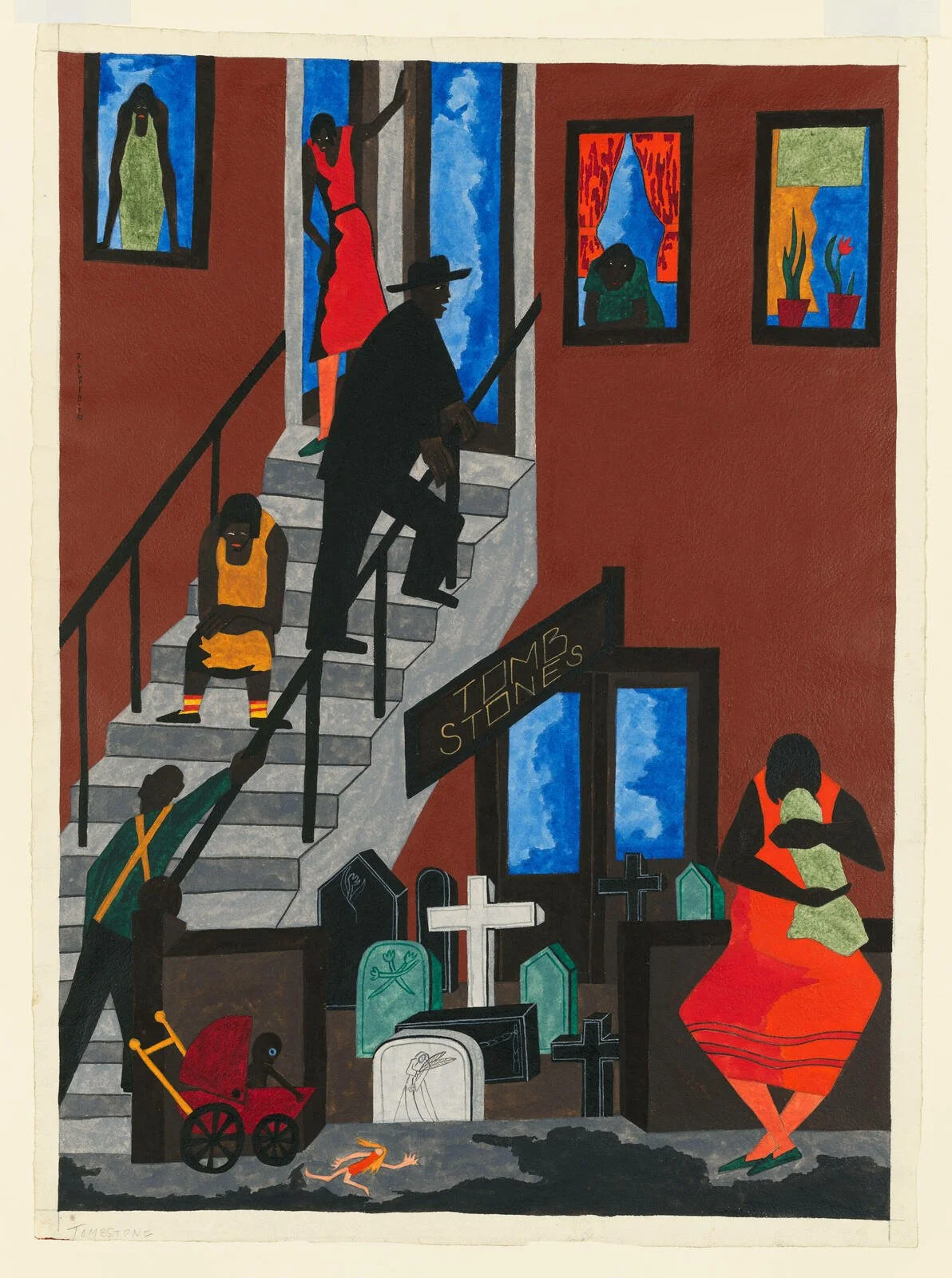

Tombstones (1942) by Jacob Lawrence. Opaque watercolor on paper; 30 7/8 × 22 13/16 in. The painting “encapsulates the full sweep of life within the African American community, from the cradle—the baby carriage at left, the Madonna-like mother and child at right—to the grave, marked at center by the tombstone seller’s wares.” Image and quote source: Whitney Museum of American Art

Anno Domini

the new year is already

inviting me to have blind

faith in new life, to let the

paid theologians ask about

the existence of God, not

to see grey clouds covering

light, to dispatch flowers to

graves and listen closely to

songs inspired by the very

first manger. to tell the truth, I

expect God not to live elsewhere

next year, to find time to talk at

length to poor single mothers,

border-crossing refugees, and

homeless migrant kids. in the

new year, I would like to hear

less about the purity and gentleness

of the first-century Jew lynched on

a tree and to notice more confessional

types with hearts to feel, and sorrow

in their eyes finding the dark-colored

Galilean in brothers and sisters of the

same hue who never hesitate to take

a stand against hate, the opiate church

and the instinct to save oneself. in the

coming days, I hope we can love God in

the very flesh sacred literature says

is varied and good.

Club Q

beloved, afraid of living on these

shores for unapologetically loving

those who place a kiss on your cheek.

despised by bigots who know nothing

of the embracing heart of God, you are

the rushing waters of the river that takes

us to peek into another land that rejects

the self-righteous, errant theologians, and

hateful killers who loathe the beauty in you,

divinity made. tomorrow, those who live in

places that wait for sudden and unexpected

messages from a heaven that balances all

kinds of love will sit with you at the same

banquet table, finding in the lush talk around

it every rainbow dream that from the beginning

offered this divided world the most marvelous

things. let us chase the monsters who point the

barrels of their guns into hell and declare that

love is what saves this world and all of us now

in this time of grieving.

Daffodils (date illegible) by Charles Demuth. Watercolor and graphite on paper; 13 3/8 x 9 3/8 in. Source: Demuth Museum

The Looking Glass: Far and Near (Wipf and Stock Publishers, 2023) by Harold J. Recinos

“In this collection of poetry, Harold Recinos inhabits the world of those that live on the edge of society, the migrants that cross rivers at nighttime to find refuge in a land that often turns them back. Recinos speaks of the inherent racism that people—Brown people, women, emigrants—experience in America, and he does it with extraordinary depth and beauty. This is an extraordinary collection of poems that will break your heart and inspire change in our fragmented world.”

—Marjorie Agosin

Author of the Pura Belpré Award–winning I Lived on Butterfly Hill